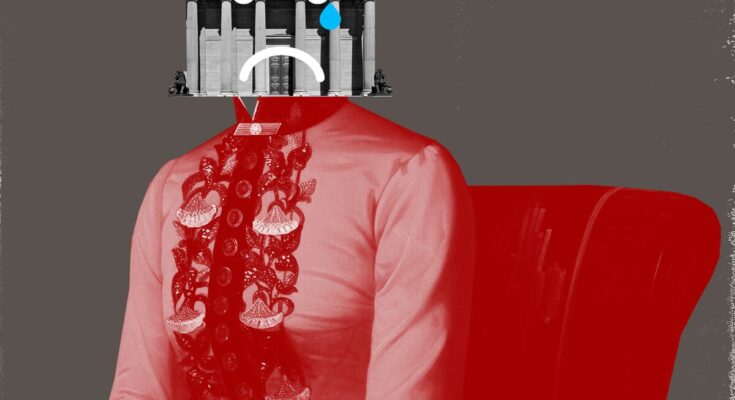

the novel Anna Carenina He begins by stating that “all happy families are similar to each other, but every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” A similar statement can be applied to the state our parliamentary regime currently finds itself in, both at the state and regional levels. In the field of parliamentarianism, the situation that most resembles happiness refers to the existence of a stable majority of support for the Government, already expressed at the beginning in the investiture session and in force throughout the legislature. If both requirements are met, the Executives enjoy not only legitimacy of origin (at the time of their formation), but also of exercise, which allows them to carry forward their legislative initiatives and, in this way, to realize their political program. If such a background context exists, it is possible to exhaust the four years of the legislature or, at most, bring forward the elections for temporary reasons, taking advantage of the most favorable political moment. This situation, which in theory should constitute the general rule, has however become an exception in Spain. The small list of happy parliamentary families bears witness to this: only in Castilla-La Mancha, Madrid, Andalusia and Galicia do the respective governments have absolute majorities in their legislative assemblies. Of course, happiness is not complete and all that glitters is not gold: the tensions generated by the serious breast cancer screening crisis in Andalusia or the mismanagement of this summer’s fires in Galicia are there to prove it.

The predominant note in the current parliamentary context, on the contrary, is unhappiness, that is, the absence of a dynamic that leads to solid and cohesive majorities that serve as support for the executives. From this first observation we can discern how the unhappiness of each family adopts its own profile and differential characteristics. First of all, we need to draw attention to cases that are characterized by having an initial and ephemeral dose of happiness, linked exclusively to the moment of investiture. In these cases what is achieved is to gather the necessary majority that allows anyone who presents themselves as a candidate in Parliament to access the Government. In reality, the support obtained is nothing more than a specific mirage, since its maintenance during the legislature is not a given, but must be obtained constantly. The Executive’s ability to negotiate with its investiture partners, as well as the margin to give in to their demands, occupy a central place in political action, which directly affects the government’s ability to carry forward any initiative at parliamentary level. The impossibility of annually approving the budget law and the consequent automatic extension of the previous ones is the most evident – and also the most serious – manifestation of the institutional short circuit generated by this first scenario, where the legitimacy of the Executive is limited to the moment of its formation, without being assured for its subsequent career. The situation in which the central government and the one presided over by Salvador Illa find themselves in Catalonia is paradigmatic in this sense.

Another type of unhappiness or parliamentary pathology is characterized by its sudden nature and its delayed manifestation. This occurs due to the fracture of the majorities obtained thanks to government coalitions between different political forces, which leaves the corresponding executives in a minority. This is what happened with the pacts signed between the Popular Party and Vox, first in Castilla y León and then in the communities of Extremadura, Aragon, Murcia and Valencia, after the last regional elections in 2023. Just a year after the latter, the national leadership of Vox decided on its own initiative that its representatives would abandon the positions held in the various autonomous governments, unilaterally putting an end to the agreements reached in the communities concerned. In this way, to stay in power, they were forced to constantly seek parliamentary support which, paradoxically, came from their previous partner. In the case of Extremadura, faced with the rejection of the finance law for 2026 and the awareness that there is no possibility of its approval, the Prime Minister, María Guardiola, opted for the orthodox solution: dissolution of the autonomous Assembly and calling for elections on 21 December. As for Aragon, we are still on uncertain ground, despite Vox having already announced that it will not support the financial law prepared by the government chaired by Jorge Azcon.

The most unfortunate and problematic case at a regional level is undoubtedly that of Valencia. The very serious episode experienced a year ago by this community as a result of the damage that caused 229 deaths and extensive material damage, was not accompanied by the immediate assumption of political responsibility by the president of the regional executive, Carlos Mazón. This, in reality, only happened recently in clearly improvable terms and after a new episode of intense social criticism on the occasion of the state funeral celebrated on the first anniversary of the disaster. Once Carlos Mazón’s resignation was presented, a phase of institutional uncertainty began, the overcoming of which allows for various solutions. Considering the existing complex political situation, resulting from the breakdown of the initial government pact signed between the People’s Party and Vox, as well as the absence of an alternative majority, parliamentary logic should lead to ending the legislature and holding elections.

This was not the decision taken and, after an initial phase of hesitation, the name of the candidate who will present himself for the investiture, Juan Francisco Pérez Llorca, was announced. From a legal point of view, it is necessary to remember that, in line with the rules established by the Constitution, the Valencian Statute requires, in the first instance, that the candidate receives the approval of the absolute majority of the Chamber. If this is not achieved, a second vote is scheduled 48 hours after the first, in which a simple majority will be enough to be invested. And in the event that this requirement is not satisfied, subsequent consultations will be held whose aim will be to propose candidates who will again be subjected to parliamentary examination. If two months have passed since the first vote and none of the proposed parties has obtained the required majority, the Valencian Cortes are dissolved and elections are called.

The achievement of a new agreement between the two political forces who signed a first and failed government pact by decision of Vox (minority partner) and who have maintained a harsh confrontation over the last year, presents itself as a challenge fraught with difficulties which places this political force in a dominant negotiating position, given the brevity of the established terms and the need to reach an agreement. The attempt to return to the starting point, attempting to re-establish a merely instrumental majority to remain in power, could, if necessary – unlikely, but not impossible – respect parliamentary arithmetic. But it will not cease to be yet another manifestation of the crisis in which our parliamentary system is mired, not so much because of its legal regulation but, above all, because of the lack of respect of political actors for the elementary uses on which it is based. A new proof of the versatility that can reach the unhappiness of any family, including the parliamentary one.