Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti visited Mexico in 1978 as part of the jury for the National Short Story Award. The National Institute of Fine Arts then organized a conference in which the author of which of us He had the opportunity to denounce the censorship suffered by writers working on a continent where military dictatorships were not necessary or guerrilla movements were busy overthrowing them. Benedetti himself had to leave Montevideo in a long exile, which took him to Argentina, Peru, Cuba, he made some stays in Mexico and then in Spain. His voice of denunciation from that day in 1978 is still alive, because it is part of a rich collection that the Mexican Radio Educación preserves and which was recognized this week by UNESCO.

This is a collection titled Sound Memory of Latin America: Exile and Resistance through Radio Educación, 1974-2016 and which brings together 481 open reel tapes, 91 compact discs and 564 digital audios, or approximately 200 hours of sound recording. The archive not only presents the voices of prominent authors, but also provides details that reveal the state of mind of these writers, intellectuals or artists. In the case of Benedetti, a note explains how the Uruguayan felt at that conference: “They say that this was an unpleasant experience, with disconnected topics and little possibility of participation. Furthermore, the questions they asked him were the same as always. His opinion on the censorship mechanisms can be heard with the militant writer.”

Benedetti’s discontent with the “same questions” of journalists not only offers golden information on the atmosphere of that day, but also on the importance that Mexico represented for dozens of intellectuals who found in this country a refuge and a space to express themselves freely, despite the Mexican people suffering their own “perfect dictatorship”, like another brilliant Latin American forced into exile, the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, so called after more than 70 years in which the PRI controlled all spheres of power in North America. country, including repression.

This collection, which testifies to the pain of exile in Latin America, began to take shape in the midst of the covid-19 pandemic, says Heriberto Acuña Palacios, head of Music Programming and the Sound Library of Radio Educación. Those nightmarish days when time slowed down due to social isolation and confinement imposed by the authorities were a good time to review much of the archives contained in the radio, which include more than 140,000 programmes, 71,000 sound tapes, 30,000 compact discs, 3,000 cassettes and 5,200 digital documents. Those in charge of the music library knew that in that enormous collection there were still gems that they had not yet classified.

“The pandemic allowed us to identify some particularities that we had not noticed, especially in programs from the seventies. We listened to some materials that were not well documented and we began to identify their value and importance. We realized that there were recordings of concerts, interviews, readings, poems and prose with important people who had arrived in Mexico or had passed through here during dictatorships,” explains Acuña Palacios.

Most of the recordings correspond to artists and intellectuals from Chile (suffocated for 17 years by Pinochet’s military boot), Argentina (which suffered seven years of terror under the command of Videla and other soldiers) and Uruguay, crushed by 12 years of dictatorship since the coup d’état of June 27, 1973. In one of the files found by Acuña Palacios’ team, the writer’s voice can be heard Argentinian Pedro Orgambide, who in an interview lasting more than seven minutes talks about his feelings in exile. Hugo Gola, also Argentinian, moved to Mexico in 1976 and gave an interview in which he spoke about the function of poetry in Latin America subjected to authoritarian regimes and the situation of poets in the region.

One of the jewels of the collection is a 25-minute interview that Guadalupe Cortés did for Radio Educación in 1980 with the Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante. The conversation was broadcast in two parts and in it the narrator talks about his decision to declare himself anti-Castro, his departure from Cuba and the pain of exile. “He talks about what he feels when he is away from Cuba and why he would not want to return to live in his country,” reads the file accompanying the audio document.

Women’s voices also occupy an important place in the collection. Among these is the Guatemalan writer Alaíde Foppa, who lived in Mexico in the 1950s due to her husband’s exile, and then moved back to this country after the coup against President Jacobo Árbenz. Her years in Mexico were of fertile literary production, she was linked to the academy and was a promoter of the feminist movement in this country, where her house was a meeting point for intellectuals in exile. Chilean journalist Ximena Ortúzar also took refuge in Mexico and in an interview denounced the repression and torture against critics in her country. And the Argentine folk musician Mercedes Sosa, in a 35-minute conversation, talks about new Latin American music and the problems in the region with the diffusion of songs.

“They left very important testimonies,” says Acuña Palacios. “The importance of this collection is that it collects voices of people who are not from Mexico and who came here to share their experiences as exiles, which means political persecution. It collects testimonies of the social political struggle in Latin America and is also a testimony of the openness that the public media had in Mexico at that time”, he comments.

Music also occupies an important place in the collection. These are groups or songwriters involved in social movements, as in the case of Nicaraguan Carlos Mejía Godoy, author of iconic protest songs such as Aand, Nicaragua, Nicaraguita, The Christ of Palacagüina OR The guerrilla’s tomb. Mejía Godoy went into exile during the Somoza dictatorship, which crushed the small Central American country in a long dynasty that lasted from 1936 to 1979. Mejía Godoy was, in fact, the author of the soundtrack that accompanied the Sandinista revolution. The singer-songwriter had to go into exile again under the current regime of his former partner, Daniel Ortega. The Radio Educación collection brings together 12 programs on the Sandinista revolution. The collection also includes a series of interviews with the Uruguayan singer-songwriter Alfredo Zitarrosa, entitled almost in private and which brings together 35 programs recorded in the composer’s home in Mexico City.

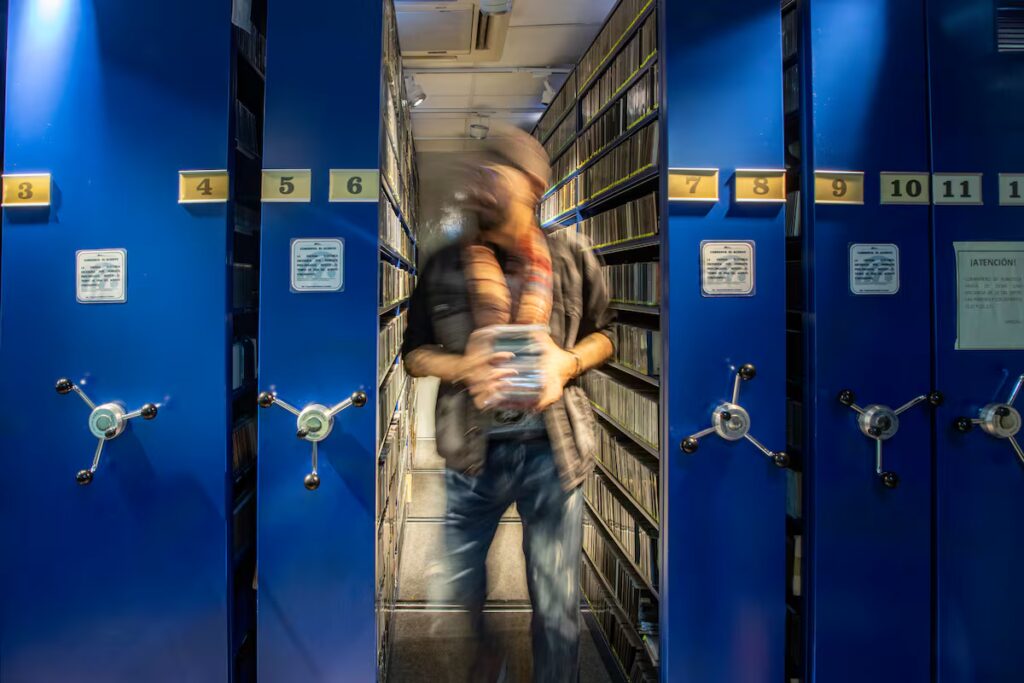

UNESCO has decided to incorporate all this legacy into the Memory of the World Regional Register of Latin America and the Caribbean (MoWLAC). “A committee composed of several Latin American countries determines the value of each dossier presented and whether it really has a regional impact,” explains Acuña. “This type of recognition gives value to the content, because it demonstrates why it can be important to talk about exile, about Latin Americans in Mexico,” says the official as he walks along the corridors that enclose the enormous shelves where the documents and the rest of the material from the collection are protected, well preserved in a vault with an adequate temperature and which avoids humidity or the presence of chemical substances that can damage this precious material.

Acuña Palacios does not exclude the discovery of new treasures in the enormous archives of Radio Educación, an institution founded in 1924 on the initiative of José Vasconcelos, Mexico’s first Minister of Education. “The collection is very large, there are things that we have to work on permanently because of the amount of material; the abundance is so much that sometimes we have to wait for periods to review the kind of material we have. There are records of people we don’t even know. We have to start digging into the collection to find things that we haven’t identified well,” he explains.