An analysis of the Catalan exile’s arrival in Mexico, both this story and another turning point What can you find at this link?. The experience of the exile of Catalan republican writers and intellectuals in Mexico is part of the imagination of many authors, but whose undertaking lasts? From Guadalajara and Barcelona, we explore the documents and obliterations that we remember of the work of authors such as Ramon Xirau, Avel·lí Artís Gener, Ferran de Pol or Agustí Bartra.

The free Introduction to the history of philosophypublished in 1964, followed by one of the most complete manuals on Mexican batxillerat. Much of your success lies in glimpsing your style, your clarity, your sensitivity and your charge of metaphors. Each philosophical era is represented by onades, who believe they will end up drowning in the dregs and lose strength to the extent that they escape through sadness. For example, classical Greece reaches its peak with Plato, and then disintegrates with the Stoics or the Epicureans. A popular assault crossed by poetry, this was the personal imprint of Ramon Xirau, one of the main exponents of the Catalan republic in exile in Mexico, who now embodies the arrival of that intellectual landing. The cultural activity of many people will be very fruitful: they will write, they will lecture, they will found magazines and publishers. But all that time has vanished in recent decades, and now the six commitments to the university continue.

I’m not in any of them. The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) is the largest study center in Latin America, a formidable cultural incubator that will give money to many people. The case of Xirau is paradigmatic. Born in Barcelona in 1924, he arrived in Mexico with his new family in 1939. His father was also a professor, degà of the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature of Barcelona, and he also entered the UNAM. “Joaquim’s exceptional article The other totem of philosophy in exile, the Asturian José Gaos. “If one looked first, Gaos’ dominance in the faculty would not have been so great. Joaquim

Xirau fill will follow the deixant del pare, addressing the fact that the seventh work focuses mainly on categories such as presence, time or silence, in addition to the connections between poetry and philosophy. «He was a promoter of vocations, a teacher», explains Teresa Rodríguez, one of the six students of the last period, to whom he will direct his thesis on a philosopher and poet of the Renaissance. During a sixty-year tribute (he will die in 2017 at the age of 93), the key director of the UNAM Philosophical Research Institute, Pedro Stepanenko, will say: “Tots som els seus alumnes”.

A contemporary of Xirau, and also of UNAM, was another Catalan philosopher, facing the Mexican sea. Juan Villoro will not be part of the republican refugees. In any case it will be a double exile in his homeland. When the war enslaves Spain, he will be sent to Belgium, and at the beginning of the Second World War he will arrive in Mexico with the new sea, here of the terratinenti. Linked to existentialism, the most current arrival is the solid intellectual support of the indigenous people, in particular the commitment to Zapatismo to all noranta. “My father belongs to a current that combined the turtlenecks of French philosophers with the crafts of nationalist anthropology,” explains his brother, the writer and journalist Juan Villoro, in a recent book about his father.

But it’s not just about UNAM and senior philosophers. The Trinidadian economist Martínez Tarragó, of the same generation as Villoro and Your stay in Scotland will allow you to contact the Department of Applied Economics at Cambridge. Martínez will be one of the promoters of neo-Keynesianism in Latin America.

The rescue of poetry in Catalan

The anthropologist Roger Bartra recalls that, when he returned home to Ciutat de Mèxic, he hung out with Manuel Durán, Pere Calders or the mateix Xirau. All Catalan refugees, lists of novels and poets with his father, Agustí Bartra. “The Catalan intellectuals who arrive will give a lot of support, they will found groups, magazines,” he recalls. His father’s group, in particular, comes from L’Espiga Amotinada and will have a strong impact among younger Mexican poets, such as Juan Bañuelos or Jaime Labastida. Bartra’s poetry will also influence prominent names, such as Efraín Huerta. But he recognizes that “this arrival is an obligation. The poets of Ara have not arrived to the meu pare nor to the rest of the Catalans. They are remembered more by academics than by the fact that they leave the institutions. The Catalan intellectuality will integrate very much into the university and into the great editorials.”

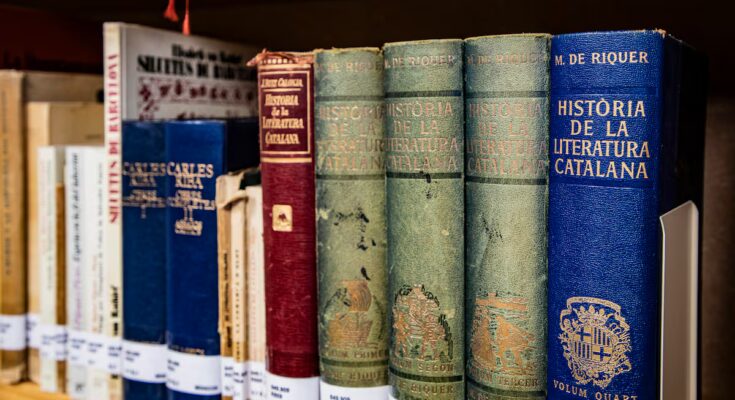

Bartra is a reference for example to the College of Mexico or the Fondo de Cultura Económica, a university and publishing house founded by republican exiles who are also owners of Mexico’s greatest cultural joys. The FCE, in fact, has published collections of poems by exiles as part of one of its six editorial objectives: saving the works is a sole obligation. The impulses will be strong especially in 2004, when “Catalan culture” will be invited to the Fira Internacional del Libre de Guadalajara (FIL). Oversurt the compilation, from that, One voice among others. Mexico and Catalan literature in exilean edition translated into Spanish by names with Agustí Bartra, Lluís Ferran Pol, Pere Calders, Ramon Xirau and Manuel Duran. The FCE will also bring together, in a bilingual edition, Xirau’s entire poetry from 2007.

Above all, Xirau’s poetic side stands out, awarded by the fish guards with the Octavio Paz and Assaig International Poetry Prize. The Mexican Nobel Prize winner will be one of his six great friends and defenders, who he will call “the home bridge” between the two sides of the Atlantic. Xirau explained with one of his six metaphors the conciliation between his six languages: “I write poetry in Catalan, which is my first home. And my philosophy in Spanish, my second home”.

In addition to Fondo’s rescues, Catalan literature in Mexico found refuge in a publishing house, Costa-Mic, independent, warrior and founded by another exile. Bartomeu Costa-Mic’s adventure is fascinating. A militant of the POUM (the Catalan part of the Trotskyist war), he arrived in Mexico just 20 years ago with a letter to President Lázaro Cárdenas, responsible for the arrival of over 20,000 republicans, for which political asylum was granted to Lev Trotsky. Shortly thereafter, in 1940, he arrived from exile, a few months after the assassination of leader Bolxevic south of the capital. He founded the publishing house and began publishing only standards to accumulate a catalog that today exceeds a thousand titles. In addition to its compatriots, Costa-Mic boasts the ability to publish the first works of Elena Poniatowska or Rosario Castellanos, in the decade of the Quarantine.

The seu fill, director of the publishing house upon the death of the patriarch in 2002, underlines that “we have stopped publishing many Catalan authors of the vuitanta. The social interest in Catalan literature no longer exists in Mexico. Only the rescues of great figures, such as Xirau, by the FCE, are guided by their prestige and their influence dels hereus entre les cultural elites of Mexico”.

Many of Costa-Mic’s first editions, popular in many cities, survive in the library of the Orfeó Català de Mèxic. Founded at the beginning of the 20th century by the first waves of migrants, it has a low profile, not finding support among the new generations who are involved in the institution. They have decided to leave the original space and move it to a smaller one, but they are promoting an interesting project for the library. “We recommend collecting and classifying more than 12,000 volumes from partner funds and we know that there is a good response,” explains Eulàlia Ribera, the group of exiles and responsible for the rescue.

Anthropologist Roger Bartra remembers joining his peers at Orfeó. “He was a rallying point, but I didn’t like him because he was a spirit of nationalism. He wrote his poems in Catalan, but he didn’t share the nationalist ambitions.” Bartra fills one of Mexico’s most important intellectuals. The second assault The cage of melancholy: identity and metamorphosis of the Mexican It is an essential work for the country’s cultural studies, a face-to-face response to the canonical (and polemical) The labyrinth of solituded’Octavio Paz. “The culture that evolved here in Mexico was determined by European education, it will inherit a cultural tradition that will help many, and this is the condition of many people who are in exile,” emphasizes Bartra as one of the derivatives of the arrival of the peer generation.