Humanity has remained trapped in a dangerous cognitive dissonance: as global warming accelerates and no corner of the planet escapes its destructive blows, the international fight against climate change within the United Nations is going through its worst moment since at least the signing of the Paris Agreement ten years ago. The great paradox is that the world has never been as prepared as it is now to replace the main culprits of the problem, fossil fuels, thanks to the progress of renewable energy and electric mobility.

Economist Laurence Tubiana, considered one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, has been involved in climate diplomacy for three decades. But he admits that he has never “seen such aggression” against anti-warming policies as that exercised by Donald Trump’s government inside and outside the United States. “We are facing an ideological battle, a cultural battle, where the climate is in that package that the United States government wants to defeat,” Tubiana warned a few days ago in one of the dozens of briefings that precede each annual climate summit.

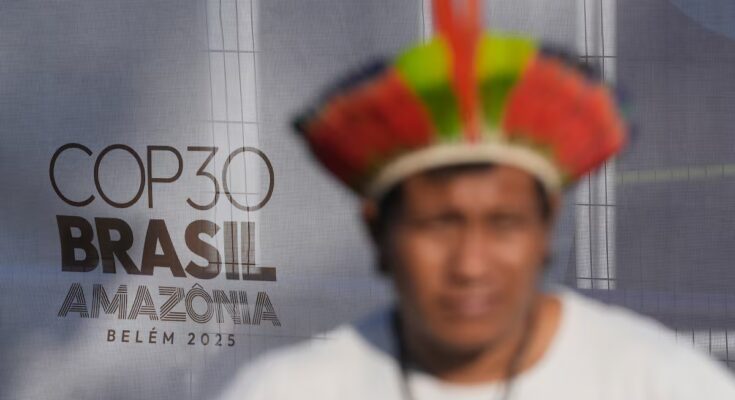

COP30 begins this Monday in the Brazilian city of Belém. It does so with the confirmation of a large failure to comply with one of the points of the Paris Agreement: all its members (195 countries) must periodically present plans to reduce greenhouse emissions. The third round of the NDC (the acronym by which these plans are known) with the national reduction targets for 2035 was supposed to be sent to the UN this year. But so far only 80 countries have done so, 40%.

Five economies were responsible for 60% of global emissions in 2024: China (30%), the United States (11%), India (8%), the European Union (6%) and Russia (5%). Of these, only three have presented new reduction plans for 2035 to the United Nations, and all of them are also out of time: China, the EU and Russia.

In the case of China and the EU – the 27, after some very tough negotiations, concluded a deal this week – their targets are below the path set by policies already in place, according to analysis by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). That is, they do not reflect an increase in ambition. In Russia’s case, the 2035 target is above the trend of its current policies. That is, it expects more emissions than would result from the measures it has in place, mainly because of its open commitment to natural gas.

Then there are the absent ones, like India, which has not yet presented its cut plan. And those who have directly slammed the door on the fight against climate change: the United States. Before leaving the White House, when he already knew he had lost the elections, Joe Biden presented a new NDC to the UN with ambitious goals for 2035. But as soon as he returned to power, in January this year, Trump signed an executive order to exit the Paris Agreement, which will materialize at the beginning of 2026 due to the internal rules of the treaty, which establish that a year must pass for it to be implemented. formalize an abandonment.

Although it was clear that Paris was a dead letter for Trump, the US State Department a few days ago asked the UN to include a note analyzing the reduction plans in the report. That text made it clear that the United States was dissociating itself from the treaty and Biden’s NDC. Despite all this, “the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions are expected to continue to decline, but at a significantly slower rate than expected before recent changes in its policies,” says Anne Olhoff, director of the Copenhagen Climate Center and coordinator of the recent United Nations report.

But the attitude towards climate policies of the Trump team, led by Marco Rubio, head of the State Department, goes beyond simply staying on the sidelines. Tubiana talks about forms of harassment or bullying (bullying in English) to the rest of the countries. The most notorious episode occurred a few weeks ago, when Rubio issued a statement threatening sanctions and tariffs against those who supported a tax on emissions from international shipping. That tax was not applied.

Tubiana believes that the current landscape is completely different from what happened in 2017, after Trump won his first presidential election. Then he also took his country out of the Paris Agreement, but no one followed in his footsteps. Far from backing down, the EU then reacted by launching the Green Pact, the result of a consensus between conservatives and social democrats, as well as left-wing and environmentalist groups.

Now within the EU, the advance of the far right has led many moderate conservatives to also reject environmental policies. This led to the easing of EU climate measures and the freezing of the European NDC until the last minute.

Pep Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project, also believes that we are going through a “complicated” time due to Trump and other “right-wing governments eager to leave the fight against climate change behind”. To this Canadell adds the war in Ukraine, which has changed the flows of fossil fuel trade, particularly with Europe, now much more dependent on US gas.

On Friday, while the leaders’ conference before COP30 was held in Belém, Athens hosted an energy meeting attended by Chris Wright, US Secretary of State for Energy. He took the floor to urge Europe to import more fossil fuels from his country because the transition towards renewables “has not worked”. Wright is not the most impartial observer: in addition to being a denier, until a year ago he was CEO of Liberty Energy, one of the giants of the frackingthe gas extraction technique that has led the United States to be the world’s leading exporter of this fuel.

The transition to renewables, however, is advancing, although not at the speed needed. “Is the world moving away from fossil fuels? Yes, but it’s still at an early stage,” notes a recent report from consultancy Ember. He adds: “In the first half of 2025, growth in renewable energy outpaced global electricity demand, causing a small decline in fossil generation.” The document highlights that “the global electricity transition has reached a critical transition point with renewables generating more electricity than coal, for the first time in history, in the first six months of 2025.”

Added to this is the advance of electric cars. Another study by the Germany-based Center for Automotive Management (CAM) estimates the increase in sales of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles in China, the US and the EU at 30% in the first nine months of the year compared to the same period in 2024. In both cases, in mobility and renewables, China is at the forefront.

But despite these signs of change, major oil companies, banks and investment funds have reversed their transformation plans with the arrival of Trump. “Too many leaders remain captive to fossil fuel interests, instead of protecting the public interest,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned from Belém on Thursday. He did so immediately after underlining that “climate change is accelerating”. Proof of this is that the last three years – 2023, 2024 and 2025 – are the warmest in the last millennia, a fact directly linked to greenhouse gases, the main culprits of which are fossil fuels.

Chiara Martinelli, of the coalition of climate activist organizations CAN Europe, highlights a contradictory global context dominated by “climate deniers” in which the scientific signs of this crisis are becoming “increasingly clear”. Scientist Pep Canadell explains that “global warming continues to progress” and does so within the widest margins of the projections made. But one aspect of all that is happening stands out: “Now, two-thirds of the world has suffered climate disasters that they have never experienced before.” This helps, in his opinion, to create that “perception that climate change is accelerating”.

But faced with this gloomy prospect, Canadell reminds us that “the path to decarbonization is clearer than ever, including the electrification of a large part of the world economy”. “We are showing that it is possible to grow by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We don’t want to approach the debate with fear, but with hope, in attack, because our model works better,” Pedro Sánchez said from Belém on Friday. The Spanish president was one of the leaders who attended the previous leaders’ meeting in the Brazilian city, which was sparsely attended compared to recent meetings.