Tantrums arise from impulse, from the freedom of the unexpected. In music, a capriccio is a piece that flows without rules, that is carried away by the imagination. Perhaps all this lies in the El Capricho that Antoni Gaudí built in Comillas (Cantabria) 140 years ago, a misunderstood building that however goes far beyond imagination: every curve, every window and every tile is designed with precision, obeys a purpose and adapts to the life of those who will live inside. Gaudí’s debut film reveals a rigor that contradicts the literal meaning of his name.

The story begins in 1881, when Antonio López y López, Marquis of Comillas, financed the installation of 30 electric lanterns in the streets of that fishing village on the shores of the Cantabrian Sea, which made it the first city in Spain to have public lighting. This modernizing impulse was not an isolated gesture: it was part of an ambitious project with which the marquis and his entourage sought to transform a small fishing village into a luxurious summer resort for the native aristocracy. That economic and cultural elite, intertwined between Catalonia and Cantabria, hired Barcelona’s best architects and artists to construct splendid buildings, such as the Pontifical University and the Sobrellano Palace, the summer residence of the marquis.

And then came Máximo Díaz de Quijano. “He was the marquis’s brother-in-law and lawyer for his company, Compañía Trasatlántica, in Cuba,” explains Carlos Mirapeix Bedia, director of El Capricho. “I belonged to that generation Indians who left America to return terruca with a lot of money and a great desire to build his own palace.” In 1883 Díaz de Quijano decided to entrust his house to a young and unknown architect, without a single built work to his credit, but with a powerful environment: he had the support of his master, the architect Joan Martorell, the Marquis of Comillas – for whom he had designed the furniture for the family chapel-pantheon – and the entrepreneur Eusebi Güell, son-in-law of the Marquis. Everyone said that his talent was extraordinary. His name? Antoni Gaudí Without a doubt, 1883 was a crucial year for the Catalan architect: in addition to the villa for Díaz de Quijano, Gaudí received the commission for the Casa Vicens and the assignment of the works for the Sagrada Familia, which would become his great obsession.

A house that follows the movement of the sun

Díaz de Quijano was a dandy single and very rich; an intellectual, lover of music – he wrote the music for several zarzuelas – and passionate about exotic plants, who wanted “a small but comfortable house”. Gaudí responded with a U-shaped plan project in which he arranged eight rooms linked and ordered according to a continuous sequence that followed the movement of the sun and accompanied daily activities: the only bedroom in the house, of 42 square meters and with a huge private terrace, was exposed to the east to receive the morning sun; while the dining room and its smoking room, at the west end, closed the day with the sunset. A series of rooms were arranged between the two pieces to serve visitors and accommodate Díaz de Quijano’s busy social life, as well as other private spaces for individual work and leisure. The service rooms were located in the basement and in the attic, which also served as an insulating room.

At the center of that U, Gaudí built a greenhouse where Díaz de Quijano, a lover of botany, could grow tropical species brought from America and “realize his dream of owning a small Cuban garden here, in Comillas,” explains Mirapeix. Its southern orientation allowed this glass box to serve as an effective passive lighting and natural heating system for the entire house: it stored heat during the day and radiated it at night.

El Capricho may not have been very large – 720 square meters was a trifle for the palaces of the Comillas Indians – but it was an ostentatious work, designed to amaze visitors before they even approached the front door. The property is surrounded by a beautiful garden in which one can glimpse some of the elements of the landscape language that Gaudí would fully develop in Park Güell almost two decades later, such as the rustic stone walls that absorb the steep slope of the land and transform into benches and even a cave.

Equally spectacular is the main entrance: a circular portico, supported by four stone columns crowned by capitals decorated with birds and palm leaves, which projects vertically towards one of the most evocative elements of the building, the panoramic tower. This cylinder encloses a spiral staircase that leads to a terrace with fabulous views of the Cantabrian Sea, invisible from the rest of the house thanks to its location in a valley.

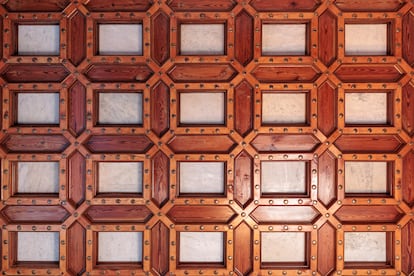

El Capricho was a very transgressive building, which mixed languages with an unusual naturalness and freedom. And, although Gaudí has gone down in history for his contribution to the development of Catalan modernism, this first work represents a cosmopolitan eclecticism: the use of exposed brick from the Arab and Nasrid tradition, the tower inspired by the minarets of Persian Islamic architecture or the neo-Mudejar coffered ceilings that decorate the ceilings mix with Gothic forms and a sense of life deeply linked to the Cantabrian landscape.

But, beyond the cultural borrowings, Gaudí – who defended that “the home is the small nation of the family” – conceived El Capricho as a tailor-made suit for Díaz de Quijano. The city presents an iconographic program that pays homage to its two great passions: music and nature. In the bathroom windows a little bird lands on the keys of a piano; a bee holds a guitar. The wrought iron railings twist to create treble clefs. The facade, organized in horizontal stripes of exposed bricks and ceramic tiles with reliefs of yellow sunflowers and green leaves, can be read as a pentagram with vegetal notes. The green zinc finials that protect the window frames also extend the botanical metaphor. Everything in the house grows and flourishes.

Gaudí, beyond imagination

It is possible that this exercise of continuous virtuosity ended up giving the house the name El Capricho, a nickname that has been used since the first articles appeared in the press regarding the project, when construction had not even begun. However, for Mirapeix it is essential that we stop”disneyfy to Gaudí”, and regrets that “there is a lot of talk about his imagination and very little about his architectural sense. El Capricho is full of details that show that Gaudí was not just a visionary, but a rigorous architect, interested in technique, comfort and the everyday experience of the home.”

Mirapeix stops at the complex catalog of carpentry that Gaudí designed expressly for the house: double-hung windows, hidden sliding doors that allowed the different rooms to be connected or divided, or even some curious sliding windows that incorporate a system of counterweights that produce music when they open and close them. The ingenious design of the railings of the living room balconies also attracts attention, as they fold up to become benches: an operation that transforms the border into a place to stay.

He also claims his conception of the profession. The studio functioned as a modern architectural firm: Gaudí designed the house from Barcelona, and it was his collaborator, Cristóbal Cascante, who supervised the work in Comillas. Even with the limited means of the time, they managed to erect a very complex building in just two years.

Unfortunately for him, Díaz de Quijano barely managed to enjoy El Capricho: he died a few days after the house was completed, in 1885. In 1914, his heirs removed the greenhouse to add more rooms, and after the Civil War, the building was abandoned for decades. Its recovery occurred in 1988, when it was restored to house a restaurant. Since 2009 it has functioned as a museum.

For Mirapeix the challenge remains the same: preserving without freezing. “It’s not just about preserving a building, but about keeping its architecture alive.” Among the upcoming projects he mentions the partial reconstruction of the roof, the reconstruction of the greenhouse and the replacement of the internal lighting. “I would like visitors to be able to experience the atmosphere of the rooms exactly as when it was finished,” he enthuses, “to understand how sunlight passes through the house during the day.”

Because El Capricho breathes, teaches and excites. Its validity and beauty lie in the ambient intelligence of a house that, 140 years later, continues to rotate with the sun.