The existence of various rights in Chile is a relatively new phenomenon. For years, after the return to democracy and contained in the minimum modesty that should accompany those who were an essential part of the cruel Pinochet regime, the right coexisted in the same coalition. Within it, ultra-conservatives, libertarians and capitalists were strong, as well as other tendencies that favored the combination of a small state with little involvement in the economy, but strong control of public order and sexual behavior. That coalition began to crack in 2017, with the emergence of José Antonio Kast and his Republicans, and ended up dying in 2025.

In this week’s elections, a variety of right-wing parties face off, presenting important differences in programmatic, historical and stylistic terms, but which will most likely unite again without too much hesitation in the second round in December. This reflects the fact that, unlike other countries, Chile never carried out the process of sanitary fencing that isolated the dictatorship’s collaborators from public life. On the contrary, in the 1990s and 2000s it was recurrent to see figures from the Pinochet government transform into active opponents of the transitional governments, even within Congress.

The conventional Chilean right, the one that is the direct heir of the two governments of Sebastián Piñera, is represented today by one of its closest allies (and, at a certain point, adversary): Evelyn Matthei. Piñera led a reconversion of his sector based on his rejection of dictatorship. In doing so, he renewed the democratic credentials of the (current) center-right but, in the process, he irremediably alienated those who see the dictatorship as a moment to be imitated, or at least admired. Matthei today represents a right that maintains a commitment to the principles of liberal democracy, but which has made the same mistake as its counterparts in other parts of the world.

This right, under pressure from its more extremist cousins, came out to try to play on the rival’s pitch. When his opponents proposed a harsh crackdown on crime, even at the expense of human rights, Matthei doubled down on his position. But this strategy, followed by conventional right-wing parties around the world, has not worked for anyone. Instead of preserving their identity, Matthei and his entourage made the mistake of disguising themselves as far-right; but usually people prefer the original to the copy. When he tried to retrace his path, the damage was already done. Today Matthei and his sector are fighting for third place in the presidential polls, a reflection of the same failure suffered in 2021 at the hands of Sebastián Sichel.

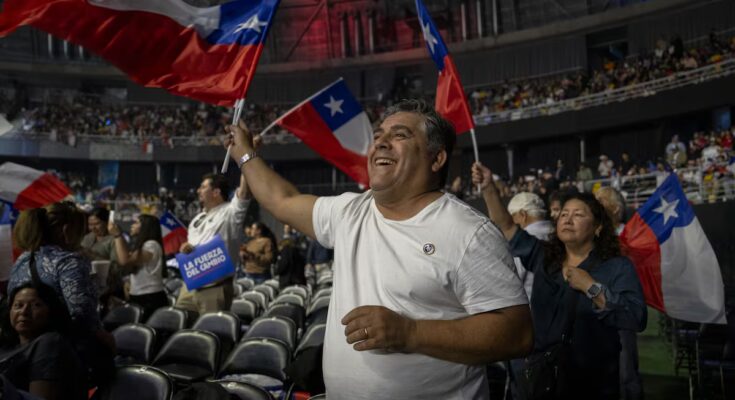

The best positioned candidate on the right is José Antonio Kast, who is competing for the third time to reach the Palacio de La Moneda. Kast chose the path of his European colleagues, encouraging the creation of his own party and building citizen bases. In a recent book, Albertazzi and van Kessel argue that European radical right parties are recovering the mass party model, with strong local ties and clear ideological positions. In an era when it was believed that politics was based on social networks and low trust in parties, Kast seems to have learned the lesson from the other side of the Atlantic.

This should not be surprising for two reasons. On the one hand, that was the party model that the UDI had had for years, the party that Kast abandoned because he believed it had moved away from its principles. On the other hand, Kast is a recurring guest of the European far right, alongside leaders such as Orban, Meloni or Abascal. The big difference is that, on this occasion, Kast and his team hid their true ideas regarding feminism, reproductive rights or sexual minorities, focusing their speech exclusively on security and anti-immigration measures. Without a doubt, an outstanding student of his European teachers.

The third right is represented by MP Johannes Kaiser, who has built his career on YouTube, promoting extreme ideas on almost every topic imaginable. From criticizing women’s right to vote to defending dictatorship, Kaiser is more similar to the American model than to the far-right European one. His style is strident and brash, he successfully imitates Trump, Bukele or Milei. Theirs is not the slow construction of a party, but rather the mobilization of relatively isolated sectors of power. For this reason he surrounded himself with evangelical leaders, libertarians and other exponents of the far-right underworld. Kast’s presence has so far been functional for Kast, as it allows him to attract a more radical electorate while Kast behaves more moderately. However, his rise in the polls in recent days has unnerved the Republican Party, fearful that Kaiser could make an unexpected (and unlikely) move. surprise

Despite the diversity of the right and its current electoral potential, it is important to view the results of this Sunday’s elections with caution. In 2020, after a plebiscite that gave 78% support for the idea of a new constitution, there were those who spoke out to promote the idea that Chile had become leftist. That idea was cut short when the draft constitution was resoundingly rejected in 2022. Then, Kast’s far-right won a majority in a new constituent process and there was talk of a shift to the right. The project resulting from this process was also rejected. From there the idea spread that the country was moderate, which appears contradictory in the face of a possible second round between the far right and the Communist Party. Perhaps, rather than drawing hasty conclusions, it is worth looking at the results with moderation and concluding that if there is something that defines the current Chilean electorate, it is its complexity and not easy labels.