The Secretary General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, asked this Thursday for countries to show “flexibility” in the ongoing negotiations at the climate summit in Belém, COP30, which once again collided with the fossil fuel wall. At the center of the debate of this meeting is the proposal to promote the creation of a roadmap to leave behind oil, gas and coal, the main causes of climate change. But, although there are countries that support this issue, starting with Brazil, the host country of the conference, there is no consensus on this point.

Guterres applauded the desire to clarify the transition away from fuel. But he also warned that Belém must commit to all countries to triple the funds allocated for adaptation to the growing impacts of warming. In his opinion, the final agreement at this COP30 will have to be a balance between calls to abandon fossil fuels and the demand, especially from developing countries, that the richest provide better financing to help them tackle this climate crisis.

COP30 is scheduled to end on Friday, although year after year the closure of these events gets stuck and never ends on time. The system under which every text, every word of every decision must be agreed upon, is based on consensus, which means that any of the nearly 200 participating countries can raise its hand and stop everything. This system, during more than three decades of talks on climate change at the United Nations, has meant that the agreements always appear downsized and watered down.

Among other things, it has ensured that the texts and agreements resulting from the COP set objectives and plans regarding greenhouse gas emissions, but do not establish reductions in the use of the main source that causes them: fossil fuels. Petrostates, with Saudi Arabia as the most visible face, have always resisted mention of oil, gas and coal. We should only talk about the gases, they defend. That is, from bullets and not from the guns that fire them.

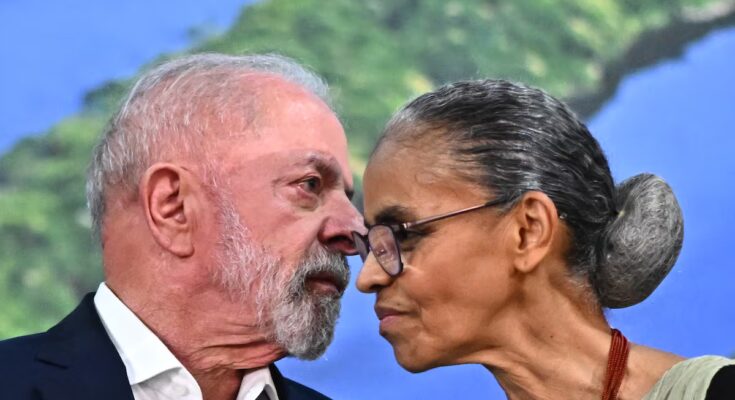

But the government of Brazil, led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, focused the attention of this summit – from which no big headlines or big agreements were expected to emerge – on that cursed issue. From the start of the conference, Lula insisted on the need for Belém to promote a roadmap for countries to break their dependence on fossil fuels. A large group of nations, around 80, although an official list of signatories has not yet been published, defends this roadmap. Opposite them are some of those states whose economies are heavily dependent on fossil fuels. And there is not much gray in these positions: some want a mandate to establish this fuel roadmap included and others don’t, so solving this problem will be the biggest problem for the presidency of this summit, in the hands of Brazil.

Lula returned to the summit on Wednesday to try to break the deadlock on negotiations, but no favorable resolution was reached as a political declaration putting the spotlight on fuel was expected to be agreed this Wednesday, so talks will continue this Thursday. At the end of the day yesterday, in a press conference, Lula insisted once again on the need to promote this roadmap.

It is paradoxical that Brazil is the one trying to introduce the issue at the summit with the most force, because it is an oil-producing country that is authorizing new exploitation. But some governments that are also producers, like Colombia, argue that this is precisely why this roadmap is needed, so that the transition is fair for everyone, including those who extract these fuels and have economies dependent on those incomes. “We need to start thinking about how to live without them,” Lula said at the summit on Wednesday.

These conferences take place under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed in 1992. In more than 30 years of summits, only one included a mention of fossil fuels, in Dubai in 2023. At that meeting, there was an exhortation to leave fuels behind. Now we want to continue with this narrative and what we want is to establish a mandate so that in the next summits this roadmap can be approved, even if for the moment without going into details.

Oil-producing countries, led by OPEC, attacked this allusion to oil, gas and coal during the Dubai negotiations two years ago. But in the end it was managed to include it in a text that obtained everyone’s consensus. Critical to this resolution was the momentum of the European Union, which in 2023 was still very focused on its green agenda, and the United States, which was still governed by Democrats.

The situation is very different now. On the one hand, the United States, with Donald Trump, has abandoned the Paris Agreement, has not sent any delegation to Belém and, in the distance, continues to row in the opposite direction to what is being discussed at COP30: this same week the White House forced to keep open an old power plant in Michigan, which uses coal, which no longer has the financial means to continue operating and which should have closed in May.

Furthermore, the European Union is not even that of 2023, due to the advance of denialist populism, and its position at this summit is not solid. For example, among the 80 countries that want a roadmap are the majority of EU members, but not Poland and Italy. In any case, after many dilemmas and internal talks, on Wednesday evening the Commission presented its proposed roadmap, with a timetable to be applied in future meetings, which hopes to help Brazil unblock the negotiations.

Next summit

Meanwhile, one of the doubts to be clarified in Belém is where the next summit will take place. Normally you don’t get to the last minute with this question open, as happened in this case, but Turkey and Australia, who were competing to host COP31, have so far kept their positions firm. Finally, a consensual solution was sought: the summit will be held in Türkiye, but will be chaired by Australia. The presiding country is the one that leads the negotiations.

If the issue had not been resolved, the summit would have been held in the German city of Bonn, where the headquarters of the United Nations climate change area is located. But Germany is not at its best in the fight against climate change. And German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is not currently Belém’s most beloved figure. After visiting the summit, already during an event in Berlin, Merz said that none of the members of the German delegation present at COP30 wanted to stay there and that they were happy to “go back to Germany”. These words sparked the anger of the Brazilian government and media. The German government announced on Wednesday that its country will contribute 1 billion euros to the tropical forest fund launched by the Brazilian government during this summit, a step applauded by Lula’s executive.