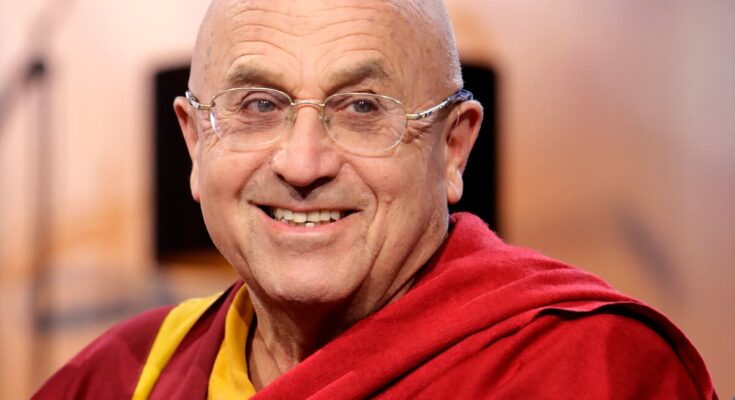

I met the Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard last October 8, when we both shared the set of The great librarythe only major television program dedicated to books broadcast in France; Ricard spoke about Lumières, a book containing photographs taken over the past 60 years during his travels through the Himalayas, India, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet. Coincidentally, six days later, that man’s face appeared on the entire page of this newspaper’s website. “The happiest man in the world, a Buddhist monk, didn’t lift a finger for others,” reads the headline. The text is a fragment of a work by the historian and journalist Rutger Bregman, and states that Ricard practiced meditation for more than 60,000 hours and that an experiment carried out in 2001 by a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin established, thanks to images of Ricard’s brain obtained by magnetic resonance imaging, that the French monk was the happiest man on the planet. “Here we are,” Bregman concludes, barely suppressing his contempt (or his indignation), “a guy who has spent 60,000 hours – 7,500 working days, the equivalent of 30 years of uninterrupted work – in his head (…) 30 years of not lifting a finger to make the world a better place.” Safe?

Born in the heart of Parisian intellectual life – he is the son of the thinker Jean-François Revel – Ricard studied molecular biology at the Pasteur Institute and, after presenting a doctoral thesis directed by François Jacob, Nobel Prize winner for physiology, he dedicated himself to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism. Since then he has written various books (on the art of meditation, in defense of altruism, happiness, animals) and has participated in numerous investigations published in scientific journals dedicated to bacteriology, psychology, social psychology, neuroscience or neuropsychology. Ricard is also a photographer: an extraordinary photographer, as he has demonstrated Lumieres and proclaimed Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Matthieu’s spiritual life and his camera are one,” wrote the masterful French photographer. “From there emerge fleeting and eternal images.” Can it be said of a man who has done all these things that he has done nothing to improve the world? Don’t thought, science and art contribute to making reality a more habitable place? In case your answer is “no,” I will add that Ricard founded a non-profit association, Karuna-Shechen, in 2000, which for two and a half decades has been developing and managing primary care, education and social services programs to serve the neediest population groups in Tibet, India and Nepal, with a particular focus on women and girls (Karuna-Shechen works with local partners to ensure that its programs respond to the needs and aspirations of indigenous communities). It will be said that what Bregman reproaches Ricard for is not that he did nothing for others, but that he did not do it during the 60,000 hours – the 30 years – that he dedicated to cultivating his own well-being by meditating. For this I have two answers. The first is that, just as one cannot be sublime continuously (Baudelaire), one cannot be altruistic continuously. The second: what if the 60,000 hours dedicated to his own well-being were precisely those that allowed Ricard to contribute so significantly to the well-being of others? Is it possible to help others if you are unable to help yourself? Won’t personal happiness be a necessary condition for contributing to collective happiness?

Don’t worry: I haven’t converted to Buddhism; I didn’t become friends with Ricard either. The great library: Sorry to be petulant, but what I’m friends with is the truth. And the truth is, Bregman couldn’t have chosen a worse example. Moral ambitionhis book is called. But it is one thing to preach moral ambition and another to practice it: the first is what Bregman does; the second, what Ricard does. I really like the first one; the second, less.