In a region marked by political tensions, weak institutions and authoritarian impulses, Chile once again demonstrated this Sunday one of its main strengths: its democratic institutionality. On an election day without incidents and with a fast and reliable count, the country launched what is perceived as a new cycle change. It did so with the naturalness with which mature democracies alternate projects, evaluate efforts and reward or punish management. In times when anti-politics is a campaign tool and not a symptom to be addressed, that normality is, in itself, a democratic victory.

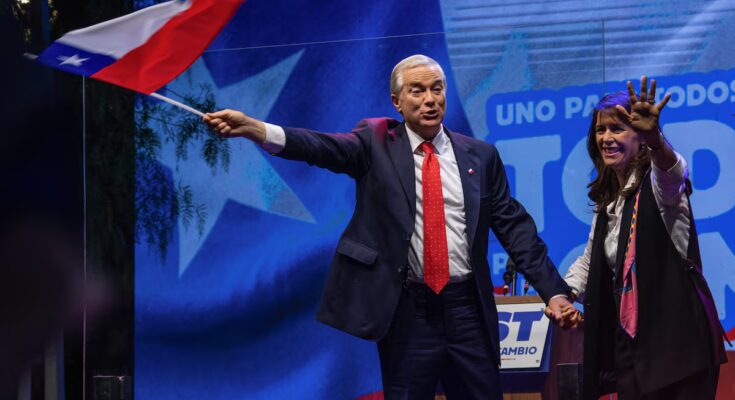

However, the picture that emerges from Sunday’s first round elections also contains signs of concern. The advance of the right, especially the leap of the far right of José Antonio Kast, which if he gathers the vote in the second round practically guarantees him the presidency, cannot be read only as a punishment to the government of Gabriel Boric or to the left as a whole. This unease exists and is profound: the middle classes exhausted by stagnation, insecurity, inflation and the perception of a state incapable of responding to emergencies have pushed the council towards more conservative positions. Disenchantment with progressivism that promised a new reality and collided with reality after arriving in 2022, parliamentary fragmentation and the limitations of the country itself are also part of this explanation. But reducing the result to a punishment vote is insufficient and dangerous.

The remarkable achievement of Kast’s Republican Party in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate speaks to something deeper: a prolonged shift to the right that can no longer be considered an accident or a temporary refuge. Chile has been sliding down that path for years. After the social outbreak of 2019, the country experienced a rapid swing between extremes: first towards the most progressive constitutional reform in Latin America and then towards a massive rejection of that project. Then there was a second project, this time carried out by the Republican right, but with the same result: the rejection of the citizens. What we see now is the consolidation of that second phase. An electorate that demands order, efficiency and certainty, even if this means moving towards exclusivist, punitive or openly reactionary discourses.

This progress should raise alarm bells. Kast promises, like many ultra-conservative leaders in the region, “common sense” in the face of what he considers identity excesses and unworkable social policies. Their project, however, presents clear risks: setbacks in rights achieved, an authoritarian retreat in the name of security, and an anti-political discourse that undermines trust in the very democracy that allows them to compete. The strength of Chilean institutions does not only consist in the cleanliness of electoral processes, but in preserving a framework of rights, balances and coexistence that has supported the country for decades. This is where Chile will have to test its democratic maturity if Kast were to govern with a parliament in which the right has more support than the left, even if it has no clear path.

Electoral punishment is not equivalent to a blank check to retrace the path taken. The country asks for changes, corrections and efficiency; not a demolition of the social pact that has allowed Chile, with all its inequalities, to become a regional example of stability. Chile has sent a strong message: elections are won and lost, governments wear out, cycles run out. What cannot be exhausted is the belief that democracy works and that its strength depends precisely on the ability to process these changes normally. In a continent where so many presidents promise to break everything, Chile has the opportunity and the responsibility to demonstrate that changing course does not mean giving up what is essential.