General Franco had pulled it out of his sleeve like a king of the Spanish bridge and was shaping it in his own image. Prince Juan Carlos could learn something from his shadow. “He was like a father to me,” she said. Franco had the minor virtues of a human being highly developed, suspicion, distrust, cunning, the sense of smell of an insect to discover the weakest and most vulnerable side of others. Instead his spirit had denied him the greatest virtues, generosity, empathy, magnanimity. While Franco was not dying, Prince Juan Carlos broke a brick with a blow of his hand; he fought against the windows; he broke his bones skiing; He came and went on his motorbike, masked under his helmet, along the paths of Segovia, where a certain Adolfo Suárez was governor. People didn’t take him seriously. He made jokes at his expense. What he thought or didn’t think mattered to no one. Only Suárez seemed to give importance to that stranded young prince.

Adolfo Suárez was then a political politician; He had the physical structure of a supporting character in a Roman film; He was like that anonymous young praetorian who appears in the middle of the projection at the foot of a staircase or in the corner of an atrium with his calf tied with a leather band, his tin skirt, his closed fist holding the spear. The tender emperor passed with an entourage of robed patricians towards the bacchanal, but the camera stopped in front of that muscular sentry and analyzed his jaw and the anxiety in his gaze. The viewer immediately guessed that that boy would end up cutting the cod, even if his co-stars ignored him anyway. This is how I described him then before he became General of the Oak of the Transition, a political adventurer who ended up believing that his destiny was to bring democracy to Spain and became a hero, a reverse path to that undertaken by King Juan Carlos, who from a hero ended up as a villain. The way their lives crossed in opposite directions is the most interesting thing about this story.

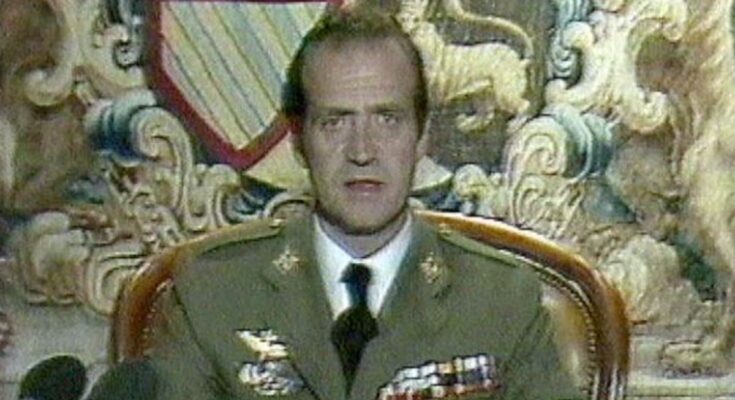

Today it is accepted as commonplace that Juan Carlos proclaimed himself King of the Spanish at 1 am on February 24, 1981. His appearance on television with a message to the nation in which he sided with the Constitution in the face of Tejero’s coup gave him genuine legitimacy. He read this speech, apparently, dressed only in the upper part of the captain general’s uniform, where four-pointed stars appeared on the cuff. The lower part of his body, blinded by the screen, was covered by civilian trousers. That submerged image is the civilian part of the coup, also left in the dark. From that moment on, Juan Carlos I was crowned by most of the politicians, intellectuals, artists, businessmen and ordinary people who fought in the streets to shake his hand.

The young monarch lived a period of general pleasure as he devoted himself to cordiality and spreading Bourbon laughter everywhere. He was the first Bourbon loved by the Spaniards. While Adolfo Suárez, when he came to the Government, was full of insults, a traitor, a careerist, illiterate – in fact he was in his time the most reviled politician after Azaña -, the King was exalted to the point of impunity, which gave him ample space to indulge in the pleasures of sex and finance. But Juan Carlos stopped being king on April 18, 2012 after asking for forgiveness from the Spanish when his hunting trip in Botswana accompanied by his lover Corinna Larsen was discovered. A king who asks for forgiveness is no longer a king. He dismounted.

Now he has just published his memoirs and is, perhaps, the first monarch in the world to do so; Written for his greater glory, with them he once again occupies the foreground of the general gossip of Spanish life, so that whoever reads them will know the ins and outs of the monarchy and will be able to delve into them as he pleases. This is the poisoned service he rendered to his son, Felipe VI, and with which he contributed to the 50th anniversary of the dictator’s death and the beginning of the Transition. Even though he helped bring democracy to Spain, in the end all that remained in the air of former King Juan Carlos was his sexual greed, his misdeeds with money and the false bottom of a broken family life. The hero of the transition was Adolfo Suárez. He was that young praetorian who in a Roman film made the camera stop in front of that square jaw that expressed irreproachable ambition. At this moment Adolfo Suárez is already in the memory of the Spanish people as a politician who demonstrated his courage.