Cities have historically been the place of opportunity. The space of encounter with the different. The possibility of accessing work, culture and, maybe, just maybe, getting closer to fortune. However, many contemporary metropolises have stopped taking care of their citizens. More and more people want a more peaceful life. Also worth mentioning is the peace of mind of having your own apartment.

In the face of global urban change, Martin Heidegger warned against the “inauthentic and uprooted life of cities”. In Build, live, think He argued that transforming a simple lodging into an authentic home was only possible in the countryside. A wave of families now agree with the German thinker for whom caring was a fundamental feature of life. When will they stop taking care of cities? When will their leaders stop investing in public facilities and spaces? When do public goods sell? When do you prefer tree decorations? Or when they are unable to offer shelter to the citizens who live there?

Heidegger believed that to live is to save the earth. But be careful, “saving the earth does not mean appropriating the land and making it our subjection.” For this reason he linked the abuse perpetrated against nature with the oblivion of our roots, that is, with the abandonment of tradition. This is important. It’s also easy to misunderstand. Defending the root means becoming radicalized, not becoming conservative. Is this what those who rebuild their lives in the countryside are looking for? Shortly after dissociating himself from the Nazi Party, Heidegger arrived in the countryside from a two-story bourgeois house with a garden on the outskirts of Freiburg. He called his new retreat in the German Black Forest, just 40 square meters, The cabin.

We saw it there. Some photographs taken in 1968 portray the philosopher and his wife Elfriede in that interior. They are already old. They put water on the stove to make tea. He had written that a man is born like many and dies like one, that is what he becomes, or ends up being, at the end of his days. These photographs demonstrate that, although contact with nature produces humility, craftsmanship brings man back to the center of the world. They also anticipate that photography is an art that seeks essence in appearance. In Heidegger’s cabin the white tablecloth was embroidered, the ceramic plates had a laurel wreath drawn on the perimeter. On the table there was a vase with fresh flowers. Both he and Elfriede have serious expressions. For photographs that reflected his life in the countryside, the philosopher wore a suit and tie. Does reconnecting with yourself require disconnecting from the world?

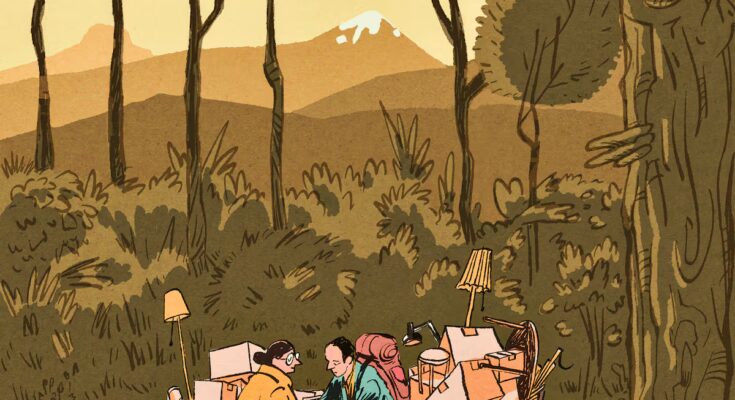

It is interesting to observe how and when each of us realizes that we are nature. The pandemic has shown that it is not about taking care of nature or taking care of it as omnipotent beings. Perhaps we are getting closer to understanding that nature will remain on the planet even when we disappear. Perhaps this search for naturalness is the spirit that inspires those who can afford teleworking and leave the city to reach the countryside.

Although it is advisable not to underestimate the harshness or neglect or lack of infrastructure and the solitude of the countryside, this ambitious escape from the city today coexists with a harder side of the same coin: expulsion. Unbridled speculation, a force far greater than the welfare state, had to come so that thousands of citizens could not afford to rent or buy a house in the city. It goes without saying that without a roof or a bed there is no possibility of working, staying or thriving in the metropolis.

Therefore, this double scenario of escape and expulsion to reach the countryside contrasts with the times when small workers’ towns were built to house the workers. It happened at the end of the 19th century in the state of Illinois, on the outskirts of Chicago. Charles Pullman had invented the sleeping car, that is: traveling by train with every type of comfort. And he didn’t want uncomfortable workers. He built a model city for the employees who worked in his factories. He called her… Can you guess? Bus.

Something similar to this line of paternalistic care also occurred in the 300 cities of Spanish colonization built, during the dictatorship, in arid lands with a modernity rooted in the austere Mediterranean tradition. Today the few cities that survive continue to be exemplary architecture. Also a paradox: demanding working conditions occurred in a modern context that had the intelligence to update tradition.

It is therefore worth asking whether moving away from the city is a necessity, a real possibility or an exceptionality. Who can do it and under what conditions? Who comes to the countryside and who is simply kicked out of the city? And a culmination: if we move away from the cities…, into whose hands or what will we leave the cities?

Throughout history, the city-countryside-suburb route has been a round trip. The colonization of the expansions occurred with the destruction of the medieval walls. But also with the arrival of those who abandoned the uncertainty of work in the countryside to seek security in commerce or industry in the city. If in the heart of the cities everything was cramped and smelly, in the outskirts you could breathe.

The formula was – today it has changed with some condominiums transformed into bunker neighborhoods – a classic: the further you get from the center, the more the air circulates, the less the square meters cost, but… the longer it takes to get there. That formula outlined the expansion of American cities. In the United States, the automobile has made travel more convenient without relying on public transportation, which continues to be lacking. In Latin America it was cheaper to build sprawling cities rather than cities densified in height. The problems of this expansionist urbanism arise when gasoline becomes more expensive, when it is impossible for so many cars to circulate in cities, or when poor public transportation forces a worker to spend four hours a day traveling from home to work.

In Spain, in recent decades – with Bilbao at the forefront – we have witnessed the deindustrialization of cities. And – with Vitoria, Barcellona or Pontevedra as guides – to its progressive renaturalisation. The Barcelona nou barris, the suburbs of Madrid and the neighborhoods that have been able to exploit the lush topography of Bilbao have established a neighborhood lifestyle that today has almost disappeared in urban centers. The Indian urban planner Suketu Mehta writes it: “When you see an art gallery appear on your street, tremble”. He was referring to gentrification, or the sale or rental of downtown apartments to the highest bidder, resulting in the disappearance of the neighborhoods’ traditional residents. After gentrification usually comes commodification, or the purchase of homes not to live in, but as investment goods. That perverse Monopoly ends up emptying urban centers of citizens at the very moment when cities are at their most beautiful. Who wants to live in an empty city? Who can do it? Perhaps only the tourists who witness the conversion of European historic centers into a sort of historical theme park.

Being happy is very difficult, whether you live in the countryside or in the city. The paradox is that many signs indicate that living in the countryside is only pleasant if you do not depend on the countryside. And living in the city begins to suffer the same fate. I never thought I’d write about politics in a decorating section. But William Morris did it when the industry – which would give us all jobs – exchanged quantity for quality. And he exchanged the honest error of craftsmanship for the plastic perfection produced in factories.

It is so difficult for a couple of generations to rent an apartment that perhaps we are mythologizing the home, forgetting that in homes underwear coexists with discomfort. Will the campaign be salvation? Or in this case too would we be better off looking within instead of continuing to look for solutions outside? Aesop wrote that the hare neither read nor enjoyed the scenery. Furthermore, he never relaxed, he always worried about arriving first. It sounds like a description of urban life except…hares have always lived in the countryside.