This is a shipment of the Kiko Llaneras newsletter, an exclusive newsletter for EL PAÍS subscribers, with updated data and explanations: sign up to receive it.

This week, Google unveiled two new AI models that are at the cutting edge of technology: Nano Banana Pro (an image generator) and Gemini 3 (a language model). The former is a leader in its category and probably the latter too.

From these press releases I draw three conclusions.

The first is speed. Every month, better models are presented from the main laboratories: OpenAI, xAI, Anthropic and Google. Gemini 3 comes to compete with Claude Sonnet 4.5, released at the end of September, with GPT-5.1, updated 10 days ago, and with Grok 4.1, updated last Monday.

The second is continuous improvement. The new models have more knowledge, are more efficient at searching the Internet, make fewer errors, program better and solve more difficult problems. But it’s easy to miss this progress if you’re not aware of it. This is why my advice is: try them. It goes so fast that something that didn’t work for you six months ago now works. For example, I now use Claude to edit my texts: I give it to him to detect typos, but also weak parts of the text. It gives me clues: “this is long”, “this paragraph is not clear”, “this example is gold”, etc.

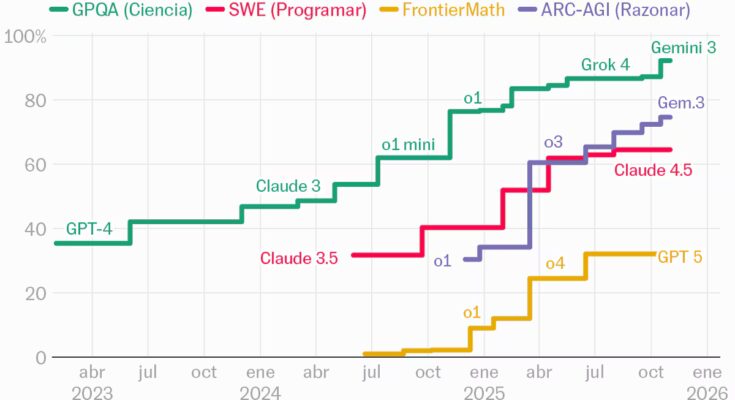

This progress is captured by reference parametersthe ratings used to compare models to each other. In the diagram above I have shown four of them, thanks to the work of Epoch AI, with key tests on science, programming, mathematics and reasoning. Each model has its strengths, but what matters is the trend: they go up in all the tests, without stopping.

It is true that evaluating these models is complicated. It is no longer enough to judge sensations because they are good. For example, to assess your math skills, you need to know quite a bit of math (imagine distinguishing a fourth grader from Albert Einstein just by chatting). Furthermore, there is the problem of “teaching to the test”. The labs train them to do these assessments well. And it’s likely that this helps them to be more capable in general… but it’s also clear that there are shortcuts, tricks that work for tests but not for real problems. It’s a dilemma that every student recognizes: study to learn or to overcome? Finally there is the complication of specialty: there are better models in design, others in writing or programming.

The third lesson? The most important thing: the models have not reached their maximum ceiling. A year ago this was a much repeated hypothesis. After GPT-4, the question was whether “pre-training” – the first phase of training, in which models learn from huge amounts of text – would continue to pay off. Some experts have spoken of a wall. And they did it again months later, with GPT-5. But this pessimism turned out to be unfounded. It’s easy to underestimate the pace of progress when comparing one model to the next, because it happens so quickly. But if you compare a current model with the best from a year ago, the leap is evident.

Oriol Vinyals underlined this this week: “there are no walls in sight”. The vice president of research at Google DeepMind, and one of the leaders of Gemini, wrote on Twitter explaining the secret of its latest release: “It’s simple: we improve pre-workout and post-workout.” He then went straight to refuting the wall theory: “Contrary to popular belief that growth power is exhausted, the team has made a drastic leap. The change between (Gemini) 2.5 and 3.0 is the largest we have ever seen.” Then he added another potential vein. The subsequent training phases, in which innovation has been made in the last year, still have ample room for improvement. They are, says Vinyals: “virgin land”.

This does not mean that large language models have no limitations. This neither rules out a future wall nor prevents a potential AI bubble (this same week, Nvidia presented impressive results and tech stocks still fell). But it suggests something important: We should expect progress in 2026.

My practical advice: use the new templates. If someone told you a year ago, “AI isn’t good for this,” that might no longer be true. Other limitations will persist. But the only way to know is to do your own testing. Many of us have a professional interest in all this. But there’s a better reason: It’s fascinating to see how far self-learning algorithms can go.

Other stories random

🏠 Rich people marry rich people

Men and women mate with economically similar people. Pablo Sempere and Yolanda Clemente tell it here with income and asset data.

People in the bottom 10% marry twice as often as chance would suggest. And people in the top 10% do it three times more often. The researcher Silvia de Poli measured it, using data from the Ministry of Finance and the National Institute of Statistics (INE).

Nuria Badenes, from the Institute of Fiscal Studies, also confirms this homogamy in her research. If we were randomly paired, only 10% of couples would be in the same income decile. But this does not happen: 16% of couples share a tenth. Furthermore, the coincidence is greater at the extremes, 19% for the lowest incomes and 33% for the highest. “The choice of a partner cannot be judged fair or unfair,” recalls Badenes, “but the fact that people with higher incomes choose to stay together contributes to perpetuating inequality.”

☀️ The future of “Solarpunk” is happening in Africa

I was interested in this article on startups who are bringing decentralized solar energy to rural areas of Africa where the traditional electricity grid does not exist.

The numbers are impressive: 30 million solar products sold in 2024, 400,000 monthly installations. Companies like Sun King sell solar kits (panel, lights, USB charger, fan) for mobile payments starting at $0.21 a day, cheaper than the kerosene they used before.

The trick lies in three convergences: panels whose cost has collapsed in recent years, mobile payments without transaction costs (very popular in countries like Kenya) and financing pay as you go that turns $1,200 products into affordable daily installments.

It is a different infrastructure: modular, distributed, financed by those who use it. I guess it can’t replace a full electrical grid, but it’s certainly better than nothing.

🌿 How to transform Spain into a zero-emission country

Spain must reduce its emissions by 32% in 2030 and 90% in 2040, which is very close to the ultimate goal of climate neutrality or net zero emissions. In this article Clemente Álvarez and Javier Galán explain why it is not a utopia.

Spain capped emissions in 2007 and has since reduced them by 38%. Industry pollutes less. The production of electricity pollutes much less. Road transport is the most problematic sector due to the level of emissions and because it has barely improved. But electrification leads to optimism: 56% of electricity is already renewable and sales of electrified cars reach 19% of the market.

Furthermore, a positive leap is expected with the advent of batteries to support renewable energy and the creation of a CO₂ market for homes and transport that sets a price per tonne emitted and generates greater incentives.

This is a shipment of the Kiko Llaneras newsletter, an exclusive newsletter for EL PAÍS subscribers, with updated data and explanations: sign up to receive it.