For years, even before her remains were found, there existed a group of women called the 12 seamstresses of the Víznar ravine. There were 12 people shot by Franco at the beginning of the Civil War, who were assigned that name even though not all of them carried out the same profession. Perhaps because it was normal for assassins to kill by guild: today waiters, tomorrow embroiderers, tomorrow farmers. However, these 12 women were united forever in the final hours of their lives and buried in the same grave for 89 years. Also on October 31, when the Spanish government, led by President Pedro Sánchez, honored them.

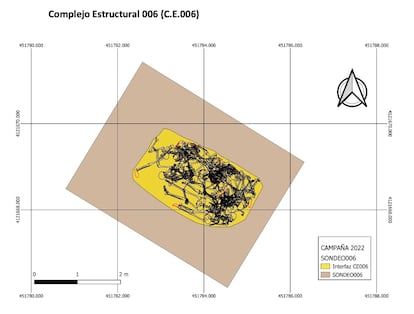

During that time, in that mass grave measuring just 2.5 by 1.65 metres, the remains of women whose lives were taken away in an instant coexisted. Their bodies were found in tomb number six of the Víznar ravine, opened in the summer of 2022 by the team of researcher Francisco Carrión, from the University of Granada, responsible for the excavations in that area. The fifth body search campaign has just ended this year.

On 6 October 1936 the 12 were taken from the San Gregorio prison-convent in Granada, where they were detained. Then, escorted by the assault guards, they were taken to Víznar: there they were murdered. The story of these twelve women is known above all thanks to the research of Silvia González, journalist and president of the Granada Republicana UCAR association, who for some years has been investigating the people killed and buried – thrown – into the Víznar ravine, with particular interest in women. Particular interest because regarding women, as González clarifies, “there is almost no public trace and it is very difficult to know things and trace their biography”.

The known history of the 12 seamstresses is built, largely, following the investigations of González, accompanied by other researchers such as Pepe Peña and Agustín Linares. They were not the first women killed in the area, but they were the first to be recorded in the execution lists. The youngest of the group was Eloísa Martín Cantal, a 19-year-old seamstress. The oldest was Enriqueta García Plata, a tobacco farmer, aged 49.

It will be difficult for the seamstresses of Víznar to change a title that doesn’t really describe them. As Silvia González says, only seven were. Some had related professions such as embroiderers, seamstresses, tailors, weavers and seamstresses, but there were also servants or workers in the tobacco industry.

These women, united in their final hours by shooting and burial in a mass grave, were honored by the central government on October 31. During the event, President Pedro Sánchez recalled the need not only to “honor the memory of the victims” of the military coup, war and dictatorship, but also to “recognize their contribution to this free Spain, in which, with many efforts and sacrifices, democracy was finally possible.”

Regardless of their occupation, these victims undoubtedly did their part for the greater good. Most of them, González recalls, were highly politicized – as members of the socialist or communist party – or unionized – from the UGT to the CNT. In other cases, however, they were captured and murdered indirectly, due to the political affiliation of a family member. This was the case of Eloísa Martín Cantal.

Silvia González has a particular interest and affection for Eloísa’s story. He lived with his father Nicolás, his mother Carmen and his brothers Nicolás, Francisca, Ceferino and Mario. His fault was his older brother’s affiliation with the UGT. Nicolás Jr. was a bricklayer and was chosen as a delegate in Granada for the election of the president of the Republic, general secretary of the Unified Socialist Youth and civil governor of the province. In reality, Heloísa never got to see those milestones in her brother’s political-union career because she was assassinated just three months after the coup.

The person who survived another family milestone was his brother Mario, who on January 4 this year recovered the remains of his shot sister. Eloísa was the first woman identified in the Víznar ravine and, with any luck, she won’t be the last.

Through his research, González managed to reconstruct part of the lives of these first victims of the Franco regime. It is known that Teresa Gómez Juárez was a seamstress, member of the PSOE and the UGT. He was also part of the Teatro Proletario group, with which he presented the show for the first time Forward with the poor of the world!! She participated in some rallies during the 1933 and 1936 campaigns, and in March of that year she was the only woman chosen by the socialist group as a substitute on the list for the municipal elections. The newspaper Granada’s defender At that time, he recorded some words he had uttered at a demonstration months before the start of the civil war: “The inclusion of women in the political and trade union struggle is of great importance, since due to our number, greater than that of men, we must decide the competition.”

Of Francisca Fernández Navarro, however, we only have information on her age at the time of death, 33, and that she was working as a seamstress in a men’s shirt shop in Granada when she was detained four days before being shot. In the case of Encarnación Estévez Martín, who died at the age of 24, she was arrested and shot due to the political affiliation of her husband and brothers.

Enriqueta García Plata, 49, was a member of the Communist Party and was seen at demonstrations. “Fruitful and generous,” her daughter described her years later. When she was arrested, she told her children: “Don’t worry, my children, I will return.” He never came back. Josefa Puertas Salinas, 23, worked as a seamstress in a sewing workshop and when she learned that she would be arrested, she hid in a cistern in Albayzín. There she held out in water up to her neck until they betrayed her.

María Delgado Zapata was 40 years old and worked as a maid. Eight years before the shooting, she had been fined for having blasphemed against the Virgin of Angustias, something that the infamous people who caused her arrest and murder had not forgotten. Ana Estévez Flores, 31, was a seamstress and lived with her mother, now a widow, and belonged to the Ascensión Garrido Jaime guild, her peer, who was an embroiderer. Another member of the guild was the 25-year-old weaver Ascensión Collantes Rosillo. Candelaria Reyes Martínez, 29 years old, worked as a maid, and for now only her place of birth is known about Adoración Muñoz Maya, the Granada town of Íllora. They were destined to spend eternity in the same grave. The efforts of an archaeologist and a memorial now give them a proper burial. Forever.