In recent days we have had a strong debate on the economic level of the Spanish people. The opinion that some social networks have become circulating in the plantations is that we Spaniards are poor. This idea, which (I have no doubt) is cunningly orchestrated by stakeholders, is based on numerous distorted indicators. Two of these debates concern the Spanish vehicle fleet. Specifically, on the one hand, the one that correlates poverty with the registrations of “cheap” cars and, on the other, the one that justifies it by referring to the increase in the average age of the car fleet. However, my position is that both indicators are not representative of this alleged level of poverty, but rather of a particular market behavior and changes in the way of consumption that have occurred in recent decades.

First of all, what is written here does not imply a denial of the obvious: that poverty levels in Spain are not negligible and that they must be fought. But what the indicators of income, wealth and quality of life tell us is that Spain is among those countries that we call first world. For example, in GDP per capita at purchasing power parity we are at the 85th percentile and in the human development index at 90. I don’t think we can think of being poor in those positions.

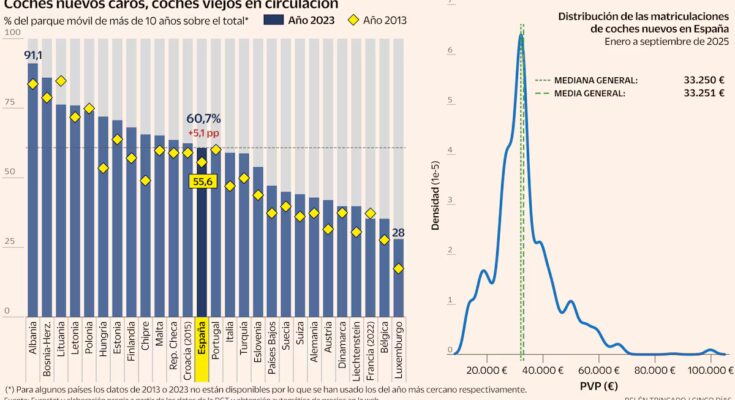

This is why trying to justify what is not in aggregate terms through the use of certain indicators is frustrating, as they generate opinions in a deceptive way. Thus, in the first of them, stating that the Dacia Sandero, a utility vehicle that does its job at a very affordable price, is the most registered car in such a way as to only indicate that we can buy only those cars does not stand up to a mere analysis of the registration and price data. If you see the panel to the right of the shared figure, you can see that if the Dacia Sandero is the best-selling vehicle in Spain, it is because it will concentrate a good part of the market in its segment or because the rest of the fleet is less concentrated. That would explain those data.

But what the distribution says is that cars with the Sandero’s price aren’t sold that many compared to the rest of the makes, models and prices. Therefore, the average price of the small tourist car sold is far higher than 33,000 euros. If we eliminate cars from the company fleet, the average increases, because companies concentrate their purchases more on lower range cars, and the same happens if we distinguish between rent and not rent. Therefore, the Sandero is not even remotely representative.

Once this is exposed, the topic is disabled. But as usually happens in social networks, when you turn off a topic based on some data, the goalposts move and the next station involves a new topic with new data. This time it’s the machine age. If Sandero is no longer representative, the next point is that Spain is poor or becoming poorer because we don’t change cars. These are getting old. And once again, this argument is simple and does not address the causes and reasons that may be behind this figure. The issue is much more complex than we are led to believe.

First of all, even if it is true that this aging occurs in Spain, it is not an anomaly exclusive to our country. Even if we are a little worse than the European Union average, we are not an extreme case. In fact, it is growing in the United States as well. The figure on the left shows the percentage of cars older than 10 years per country in 2013 and 2023, and what it shows is that in almost all of them they have grown and that in Spain this progress has been much more moderate.

But what explains this general increase in the average age of the vehicle fleet in general, not just in Spain? Well, several reports, studies and analyzes highlight a confluence of barriers to access to new vehicles (VNs), technological changes and, fundamentally, the emergence of a hyper-efficient pre-owned (VO) market serving as a catalyst.

The first and most obvious obstacle is the affordability crisis. The new vehicle has transformed into a luxury item. Since 2019, the average price of new cars has increased 38.1%, nearly double overall inflation. The supply of affordable models (those below the average price) has decreased. In recent years, access to cars is increasingly difficult, whatever your income level and the country in which you live. This indicates nothing about the advancement of poverty in the country, rather an opportunity cost balanced against other goods.

The second great wall is uncertainty. Paradoxically, the regulatory push towards electromobility, designed to modernize the park, would have slowed down purchasing decisions for a certain period. The consumer is paralyzed by doubts about the high cost of electric vehicles, the reliability of a charging network that is still in its infancy and the complexity of aid plans such as the Moves Plan. Announcements about the end of the production and circulation of vehicles such as diesel ones have also increased this uncertainty.

Finally, the semiconductor crisis (2020-2023) acted as a trigger. The halt in production and exorbitant delivery times pushed thousands of buyers, even those who could afford a new car, towards the used car market. This forced migration has normalized second-hand as a viable option.

Therefore, the rise of digital VO platforms was the catalyst that allowed the system to manage these barriers to entry. In the past, selling a car with a certain number of years was a process with high transaction costs. Today, platforms have created a liquid, transparent and professionalized market that makes VO a real and safe alternative to VN. The VO market has become an active recycling system whose function is not to renew the fleet, but to recycle the existing fleet. Therefore, to argue that this phenomenon is solely due to lack of income is to ignore crucial factors that influence the global market, not just the Spanish one.

In conclusion, both Sandero’s argument and the aging vehicle fleet are examples of how certain indicators can be manipulated to construct narratives that do not stand up to rigorous analysis. What we are really seeing is a structural change in the automotive market; a combination of rising prices for new vehicles, a technological transition that generates uncertainty, supply shocks such as the semiconductor crisis and the emergence of digital platforms that have professionalized the used market, creating an ecosystem in which keeping an old car is, quite simply, the increasingly rational decision. Reducing this complex and European phenomenon to a question of poverty is not only simplistic, but profoundly wrong. And interested.