Jerry Moore says that doubt assailed him one night in his living room. This archaeologist and writer had his cat on his lap, looking at it intently and pondering, “How the hell did it get here?” The answer to your concern is Cat Tales: A History (Thames & Hudson), for now without translation into Spanish. It is a very broad and ambitious book, written from archeology and anthropology, in which Moore takes us on a journey that lasts from the Pliocene of terrifying saber-toothed cats to kitten videos on Instagram. It is a story of thousands of years of coexistence, from mutual predation to happy domestication, which prove that the question posed by Moore has a very complex answer.

For decades, the narrative went unchallenged: Ancient Egyptians domesticated cats about 4,000 years ago. As rodent predators, cats guarded grain silos and were protected and admired. Families mourned her death, cat mummies were held with reverence, and Bastet, the feline goddess, was venerated and appeared in sculptures and paintings as the protector of home and family. From there to Moore’s living room, the leap seems logical: the cat is a useful and beautiful animal that was domesticated for human convenience and ended up stealing our hearts and wombs.

However, archeology has a habit of snatching narratives from the hands of historians. Moore, in fact, decided to explore the human-feline bond through archeology because “much of the evidence for such relationships is found not in written histories or among living cultures, but underground,” he says. And underground, in an excavation in the Neolithic village of Shillurokambos in Cyprus, something was found in 2004 that defied conventional history: a 9,500-year-old joint grave, where a human and a cat had been buried together, surrounded by offerings such as shells and polished stones. The cat, just eight months old, was resting less than half a meter from the deceased human. His bones were arranged with care and attention.

That Cypriot grave redefined feline history. For Moore, the importance goes beyond the dates. What Shillurokambos reveals is something more fundamental: the very nature of how cats and humans learned to live together.

“The concept of domestication, as artificial selection for specific characteristics and reproductive control, is very valuable,” explains Moore, also a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of California, in a conversation with this newspaper. “However, it does not appear to be relevant to understanding early interactions between sedentary populations and wild cats attracted to the mice and rodents that lived in the granaries and warehouses of Neolithic settlements.” The author explains that, for him, mutualism is a better concept: “Both people and cats benefited from these new interactions, during the Neolithic and thereafter.” Humans gained pest control and felines gained a source of food and shelter. Cats became, as Moore explains, “companions (of humans) of their own free will.”

What’s fascinating is that the domestication of cats didn’t happen everywhere. Although agriculture is widespread globally, modern domestic cats all descend from a single species: Felis silvestris lybicathe African wild cat. The cats were attracted to rodents (particularly the invasive house mouse, Mus musculus) that infested human granaries in Europe. However, Moore explains that there were no specific species of mice in Mesoamerica and so mutualism never developed.

Cats were the last animals to be domesticated, long after dogs (about 30,000 years ago) and cattle (10,000 years ago). This domestication is unique because cats do not contribute to human sustenance, guarding, or labor, and the process did not initially involve human control of reproduction, as occurred with other species. Cats were common traveling companions on ships (from Greek triremes to Spanish galleons) to protect food supplies from rats. This, however, led to cats becoming invasive species on remote islands, decimating local wildlife, which remains a huge problem today, with 400 million domestic cats doing their bidding worldwide.

intimate enemies

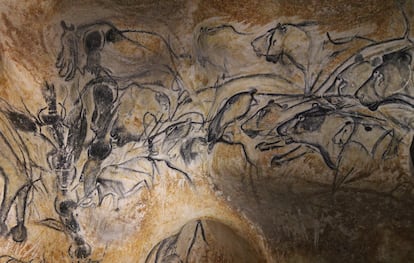

However, for thousands of years, humans and cats have been enemies. In the Paleolithic caves of Chauvet, 32,000 years ago, primitive artists carved images of lions into the rock. Big cats and humans were mutual predators and continue to be, even in urban environments; the book mentions dangerous pumas in Los Angeles and tigers in Bombay. But the extraordinary thing, Moore says, is that we are the only primates who actively coexist with feline predators. Furthermore, our relationship with them is different from the one we have with each other. excellent petdogs; it is less hierarchical, less dependent on training and more based on a strange balance between independence and proximity.

Why is this so? What is it about cats that millions of humans have fallen in love with throughout history? Moore devotes an entire chapter to exploring what he calls the “charisma” of felines; that magnetism that at the same time attracts us, generates respect in us and, at times, terrifies us. “I think the appeal is deep and universal,” Moore says. Although we commonly apply the term “charisma” to other humans, such as movie stars, rock musicians, and, not so often, politicians, “the term is applied to fascinating nonhumans, such as lions, tigers, and other felines. The fact that there has been such widespread recognition among modern people of different cultures and nations suggests a deeply evolutionary origin.” In fact, a 2018 study found that big cats were considered the most charismatic animals.

A historical reflection of that fascination occurred in the year 525 BC. The Persian general Cambyses II knew of the Egyptians’ love of cats, so he captured hundreds of them and tied them to his soldiers’ shields. The Egyptian army surrendered without a fight in the city of Pelusium so as not to harm the cats. It is the first documented surrender for the love of an animal in history.

The most curious thing is that the scientific evidence collected in the book, from ancient DNA to modern behavioral studies, demonstrates that the domestic cat is little different from its wild ancestor. Moore sums it up this way: feline domestication is so mild that “the domestic cat is practically a docile version of the Felis silvestris lybica”.

“I have lived with several cats and I have not understood any of them”, confesses the writer, in a sentiment shared, perhaps, by hundreds of thousands of human beings who currently also have a cat in their lap. “How did this happen?” Moore wondered as he observed his house cat. That mystery is, in itself, the axis of the book. The answer, still contradictory and full of nuances, lies in hundreds of thousands of years of shared evolution, from predator to ally, from ally to god and from god to companion.