What can we really know about other people? In 2014, a poet whom everyone considered a giant of his time, Francis Blundy, read a poem destined to disappear, a poem dedicated to his wife Vivien and read only once at dinner with friends and which would ultimately acquire an almost mythological aura.

Over a century later, in May 2119, Thomas Metcalfe, a scholar from a now very distant former world (the present, more or less) traverses a landscape that no longer resembles a country, a collection of lands that survived the aftermath of the Great Cataclysm, and begins to pursue clues from the lost poem, as if in those lines he can find a meaning not given in his time. Metcalfe lives in a sinking world, literally, where the great institutions of the past have been displaced by water, such as the Bodleian, now relocated to Snowdonia to save it from the floods that are consuming Oxford. Metcalfe insisted on consulting the same famous archives, hoping the revelation would never come. The obsession with The Crown for Vivien (an elusive poem) becomes an obsession with illusion: the idea that the past has a clarity that the present lacks, when it is the past itself that is incomprehensible, like the stories of Blundy’s friends, consisting of love and envy, loyalty and betrayal, a balance that is never stated.

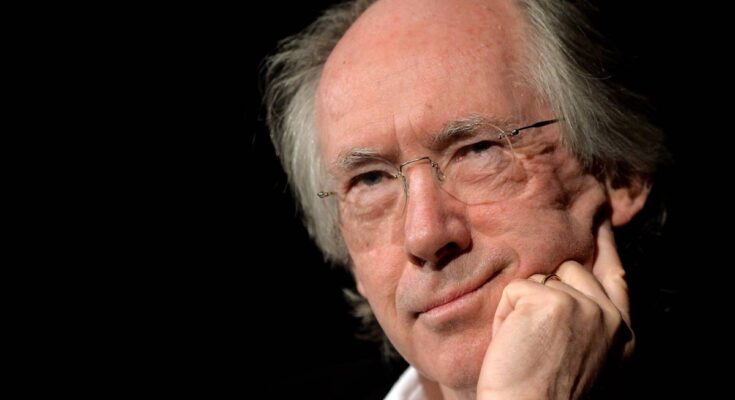

In Ian McEwan’s What We Can Know (Einaudi), in short, the underwater world is an environmental yet internal metaphor, a reconstruction of thought that seeks to interpret what is submerged and will always be submerged, the past, the knowledge of others, and the present itself. Metcalfe moves as if rationality were still a safe method and as if archives could replace understanding, and McEwan (sometimes too didascally, but whatever), observes him with a patience that bleeds into irony, letting him confront the same limits we have, in our world that believes itself to be solid while falling to pieces.

It is a reflection of knowledge (not scientific, more in the human sense) that nothing entertains: the future does not clarify the past, documents do not clarify humanity, the idea of interpretation becomes a form of resistance, a fragile and desperate way of not recognizing that what escapes us is always broader than what we grasp. McEwan this time uses the future as a minimal artifice, to separate humanity from its context and show how little is left as the landscape changes. In short, the construction of the plot is a seismograph of omission: a hunt for a lost poem that reveals more about the community celebrating it than it says about the text itself, and also a journey that illuminates a crime, and a love story, and a web of compromise, and most importantly the failure of memory as an instrument of truth. When the novel touches on what our descendants will know about us and the broken world we will leave behind, its impact is not prophetic but rather speculative: it speaks not of the future, but of the present. Because none of us, deep down, knows anyone else, and also because it is reason that exists in the present, not in the future, which sinks from day to day as if nothing had happened.