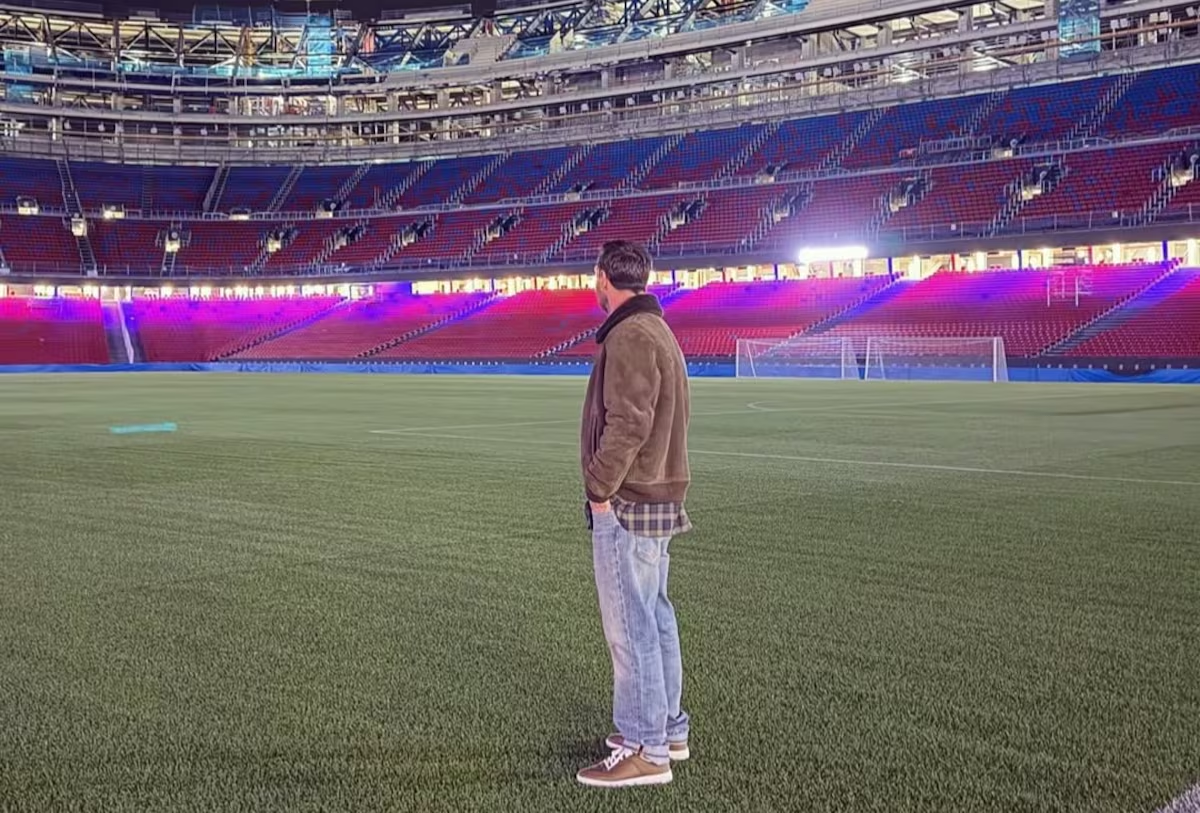

Messi looking at Camp Nou from the window of a restaurant, telling De Paul to accompany him for a moment, arriving at the door and asking to come in, putting his feet on the grass and looking up at the empty stadium at midnight, is one of the reasons why football will always be more important than the business opportunity that investors who have never had a passion, nor a shirt to pray for, want to transform it, and are asking in their buildings in Riyadh what offside consists of. That, that image, brings together all the elements with which football resists the sabotage of Infantinos and Tebas, brings together all the richness of nuances with which football dismantles prejudices and baseness.

Every fifteen days and for fifteen years, on that stage, Messi heard 100,000 throats singing his name. They were silent several times. I was one of these on the pitch, in a Clásico: it was when, after a crash, the stadium fell silent. In a way that was more impressive than the screaming. It was the famous silence of the Camp Nou when Messi was left lying on the pitch; those seconds in which suddenly the life of the culé fan passed in front of him while that of the madridista passed behind him. Another day a goalkeeper caught a ball flying through the air and hit poor Messi in the process. The commotion at Camp Nou was such (every time Messi takes to the pitch there is a dictator’s funereal silence, as if he might stand up and take note of who is speaking) that no one noticed that a penalty had been called. I was in the field and I wrote it, because you have to write everything down. “It took the Argentine a while to get up: when he did he scored a goal. Even for Stalin, when he was on his deathbed, his collaborators approached the bed, taking advantage of the fact that he was losing consciousness to fill him with insults; when he regained consciousness, Stalin didn’t take a penalty, but signed death sentences, which is similar.”

Messi in the empty Camp Nou is football’s irrational connection with its heroes in the most fantastic way possible: that of the player retired from the club with the stands once full and now empty. The Camp Nou, among other things. A club can move to another city, sell its star, change its crest or anthem. It can masquerade as a global company and even be one. But when a club is left without a stadium, everything goes out: literally, the lights. Hobbies who had to spend years playing loans and wandering, like the Targaryens, without a place to remind them why they love what they love, know this. The stadium itself is not a sporting venue: it is an emotional country. Where you enter and stop being one to become a multitude. Where parents point their fingers at the stands and say “here I was with your grandfather”, and they know who he was with.

It may seem exaggerated, but: no club is completely its own master if it has nowhere to live. A stadium is therefore not just an infrastructure, but a home. The fans return like those who return to church, like those who return to their homeland after years. It doesn’t matter if there is dust, if work is missing, if something is still incomplete: the important thing is to put your feet back on the same steps, look at the same grass, still feel that that place names you and recognizes you. And the fact that the first to enter from abroad was Messi, who passed, closes and opens a circle.