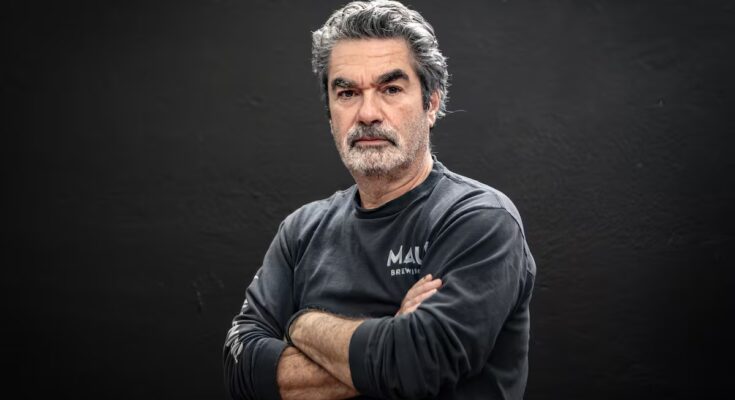

It was the last days of October and Joe Berlinger was enjoying them to the fullest in Mexico City. While responding to texts and emails on her cell phone, she tried for the first time a pan de muerte, a traditional Mexican dessert made to honor the dead during Day of the Dead celebrations. He tried it for the first time, his frown relaxed and he gave a thumbs up, a little sugar smeared on his moustache. His presence in the capital was not expected, but it was a pleasant coincidence. The initial plan he had with his wife was to travel to Italy, but he didn’t feel so encouraged. There was something in the Mexican capital that called to him. And so it was. A few days later he received a call from the organizers of DocsMX, the capital’s International Documentary Film Festival which, in its twentieth edition, decided to honor him for his contribution and his career in this type of cinematography. The American documentary maker is taken into consideration father and teacher of true crime, a genre of non-fiction that has become popular in recent years, based on true crimes and detailing the events covered.

The work of Berlinger, 64 years old and originally from Bridgeport (Connecticut), United States, has highlighted issues of social justice in his country, through famous and recognized productions such as Brother’s keeper (1992), the trilogy of Paradise lost (1996, 2000 and 2011) —with an Oscar nomination—; or his intimate look at how painful, funny and difficult the creative process can be within a band like Metallica, as he did with him Some kind of monster (2004).

Since he began working in the documentary world more than 30 years ago, he has seen how the landscape for this genre has changed. He says that back then, in the early 1990s, nonfiction productions could only be offered to networks like HBO or PBS. Now, with the different services of streaming on demand, documentaries have become “very popular,” he says. However, this moment, he explains, has two sides of the coin.

“If you ask me, I think it’s a much healthier environment. But young filmmakers who have been making films for only 10 years probably feel that things have gotten worse. During the pandemic (due to Covid-19), the platforms were buying everything and there was a constant fight to be the most popular. In those years the spending was excessive. They were commissioning productions left and right. And when the pandemic was over, I think everyone, especially the chains, understood that it was not feasible to continue spending without control. So the sector has contracted,” he says.

Berlinger recalls that although he already had his two most famous documentaries, Brothers Guardians AND Paradise lostunder his arm, during the first decade of his career he earned his living directing television commercials. “Documentaries weren’t very profitable. It was very difficult to get them seen. Before, in 1990, if 400 people saw my film in the cinema in a week, I thought: ‘My God, 400 people have seen my film!’. Now, tens of millions of people can see something on Netflix. So it depends on your perspective and how long you’ve been in the industry. From my point of view, the world has become much more receptive to documentaries,” he adds.

The popularity of non-fiction in recent years is believed to have opened the door to documentaries focusing on true crimes. However, he believes the market has bifurcated. Berlinger says his conviction to make this type of production comes from the school of investigative documentary. Its primary goal has always been to address wrongful convictions. It is not for nothing that his films have achieved the success of seven people. Paradise lost For example, he managed to free three people, one of whom was sentenced to death. «For me, crime has always been an instrument of social justice in the criminal field», he clarifies.

“However, with the popularity of true crime In some productions a completely different tone has spread, too frivolous and without respect for the victim. In the United States, there are podcasts in which victims or crimes are ridiculed for entertainment purposes. It’s not just him true crimethere is also the docuentertainmentwith little investigative rigor”, adds the director.

According to him, one aspect that is not encouraged enough in crime documentaries is that they no longer develop gradually. At least not like before. And also, in this sense, he is critical of some of his more recent works. He states that what binds streaming What they want now are past events to simply recount without thorough investigation. Mention it again Paradise lost which, between his three deliveries during the monitoring and investigation of the case, was filmed in 15 years. “We didn’t know how long it would take to take shape. I think it’s increasingly difficult these days if you want to get funding from a network. Executives don’t want to give you an open-ended project where you just follow a story,” he explains.

There are also voices who believe that the true crime revictimizes people who have been affected by an event or with this genre a serial killer is romanticized and idealized. Berlinger cites as examples two productions he worked on with Netflix about serial killer Ted Bundy. One of them imaginary, Extremely cruel, evil and perverse (2019) —with actor Zac Efron as the protagonist—. The other was a documentary called Conversations with killers: the Ted Bundy tapes (2019). «The documentary showed a lot of violence and was accused of glorifying it true crime. The film showed no violence and was also accused of glorification. I think there’s just widespread criticism. For some reason, people don’t like the genre and think we’re glorifying it. But if you’re honest, I think they are stories with a very important warning for the next generation,” says the documentarian.

Berlinger states that, when approaching the production of a documentary, one must go “where the truth leads”. Following this philosophy and way of working, he found that many of his films never ended with the initial hypothesis or idea at the end of recording.

“I always ask myself, ‘What is the social justice reason for telling this story?’ If I can’t answer that question, I’d rather not tell it, because it comes with an added responsibility. If you’re telling stories about the worst day of a family’s life, you have a responsibility not to do it in a way that trivializes or ridicules the situation,” he concludes.