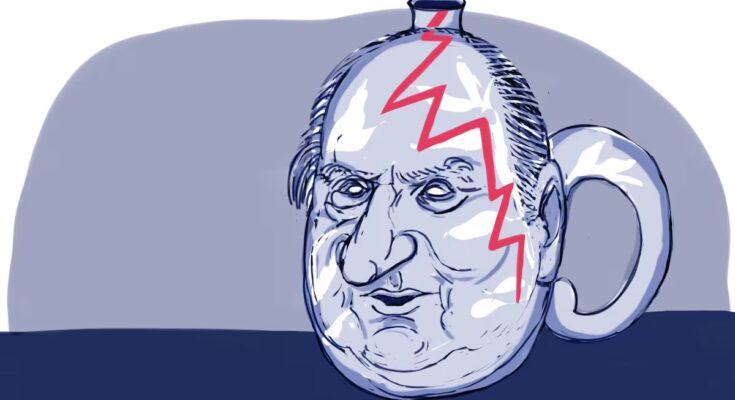

Juan Carlos I went from being a sort of political totem to a questioned figure. This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of Franco’s death, the coronation of Juan Carlos I and the beginning of the Transition. It is logical that favorable and unfavorable opinions about the king and his career are reactivated. The publication in French of some of Juan Carlos’ memoirs added spice to the topic.

At this point, the reputation of Juan Carlos I is greatly damaged. Although Justice did not want to judge him, making use of article 56 of the Constitution which establishes that “the person of the King is inviolable and not subject to responsibility”, several pecuniary crimes were accredited during his reign. We know that the king had fortunes in tax havens, that he received scandalous “gifts” from the Gulf monarchies, that the secret services had to cover up his adventures on some occasions and that public money was used to buy the silence of some of his “friends” (as revealed by Emilio Alonso Manglano, who was director of the CESID). In short, an unedifying story that caused his abdication in 2014 and his subsequent transfer to Abu Dhabi, thus following in the footsteps of his grandfather Alfonso XIII and his great-great-grandmother Isabel II.

Recalcitrant monarchists cling to the role played by Juan Carlos I in the Transition. In a certain sense, they believe that their contribution to the democratization of the country compensates for their personal weaknesses. Yes, he could have made mistakes and mistakes in his private life, after all he is human, but his political legacy cannot be erased. In this perspective, the king, in an act of maximum generosity, renounced the vast powers inherited from Franco in favor of the democratization of the country. He had a high vision and a sense of history, in a similar way to how later, and on a smaller scale, Franco’s prosecutors made haraqiri by passing the political reform law, the law that made the democratization of Franco’s institutions possible.

In reality, things were a little more complicated. There is no doubt that the king opted for democracy, but, on the other hand, the first phase of the Transition, the one that ran from Franco’s death on 20 November 1975 to the general elections of 15 June 1977, was strongly conditioned by the need to make democracy and monarchy compatible. The king was willing to reform Francoism from above and below, until it became a liberal democracy, as long as the monarchical institution itself was not subject to revision.

Upon Franco’s death, the interests of monarchists aligned with the interests of democracy. An authoritarian monarchy led by Juan Carlos I would not have survived in a Western Europe where, after the transition of Portugal and Greece, Spain represented the last authoritarian vestige. A dictatorial regime in perfect political isolation would have had no future. Juan Carlos was perfectly aware of this. The condition for the possibility of a stable monarchy was a democracy.

The problem lay in the fact that Juan Carlos de Borbón had sworn on two occasions to respect the Fundamental Laws of Francoism and to remain faithful to the principles of the National Movement: he did so when he was appointed successor, on 23 July 1969, and, again, on the day of his coronation, on 22 November 1975. Therefore, the king needed the political change to take place according to Francoist legality. Any other option would have been a violation of his oath. If Juan Carlos had not kept his word, there would have been two problems. On the one hand, the military would have considered him a traitor and would probably have rebelled against him. On the other hand, if the transition had occurred through a rupture, the opposition would have questioned the monarchy and, perhaps, a referendum on the form of government would have been called, a difficult risk for the king to take at a time of great uncertainty.

Furthermore, for the Francoists, the king was a guarantee of continuity. With Juan Carlos there would be reforms, but no major shocks. They therefore thought of ways of opening up the regime from within, of reforms that the king could sanction without putting the monarchy at risk. The first government of Juan Carlos I, that of Carlos Arias Navarro and Manuel Fraga, attempted to do this through a series of measures that failed to clearly penetrate the institutions of the dictatorship (although these measures were very timid, since they granted veto power to the Francoists in the new system). After much hesitation, Juan Carlos removed Arias Navarro and replaced him with Adolfo Suárez, who, with the advice of Torcuato Fernández-Miranda, proposed a quicker method to be able to hold free elections without breaking with Franco’s legality. It was a question of approving a new fundamental law of the regime, the eighth, which would have modified the existing ones, creating the Cortes with two chambers elected by universal suffrage (in the case of Congress, using a proportional formula); Furthermore, the new legislature would have the ability to approve constitutional reforms by an absolute majority (thus eliminating the two-thirds requirement applied to basic laws).

This very baroque formula of political change (what was then called the move “from law to law”) was ultimately brought about by the monarchical imperative, from which the regime’s reformists also benefited. Juan Carlos I couldn’t break with Francoism. If Spain wanted democracy, it had to build it by guaranteeing legal continuity.

The procedure followed was not neutral: it had consequences on the transition and on the democratic system. Among many other things that could be mentioned, the pace and scope of change during the first phase of the Transition (until the elections of 15 June 1977) were decided by the reformists of the Franco regime, with very low participation of the opposition forces. One member of those elites, José Miguel Ortí Bordás, made it clear in his memoirs: “We wanted controlled political change, which at no moment could escape from our hands.” Furthermore, this way of carrying out the Transition guaranteed the impunity of Franco’s elites and prevented an open and necessary debate on what happened during the dictatorship. Finally, legal continuity made it easier for the state (security forces, judges, senior officials) not to be shaken by political changes (the Army went through a major transformation in the 1980s).

Given the economic and social conditions of Spain in those years, it was very likely that Spain would end up becoming a democracy, but there were several paths to democracy from a dictatorship. Many analyzes of the period presuppose that the only possible path was legal continuity, eliminating at the root the contingency that existed in the short term. In hindsight, it always seems like things couldn’t have been different, but there were multiple possible transitions. The path that was ultimately followed was not inevitable. The king favored democracy, but he did so by betting on political change in the service of the monarchy, in which the democratic foundations were not as solid as they could have been.