It is not difficult to find women on social networks who identify themselves as “traditional wives” or tradwives: people who, by their own decision, dedicate their time to the home and to satisfying the needs of their husbands.

Unlike their American or European counterparts – who tend to present themselves as part of the middle or even rural classes – i tradwives The most visible Mexican women are, for the most part, urban women who openly recognize themselves as belonging to the upper class. It is common for them to be called “Lord of Las Lomas” or “Sanpetrinas”, referring to the high purchasing power areas of Mexico City and Nuevo León.

On social networks they are seen cooking, organizing school or social events and taking care of their children. However, unlike the international imagination, the tradwives Mexican women often frequent high-end gyms, eat breakfast at upscale restaurants, frequent beauty studios, or participate in recreational activities at private clubs.

The question is whether this strong class connotation really constitutes the essential profile of tradwife “Mexican style”, and yes, as digital platforms suggest, this lifestyle is growing among younger generations.

To explore this, I scanned INEGI’s National Employment and Employment Survey for married women – or living in a common-law union – who do not work, have no intention of working, and report no need or desire to do so. That is, women dedicated to the home whose family unit depends entirely on the income generated by their partner, a man officially identified as the “head of the family”.

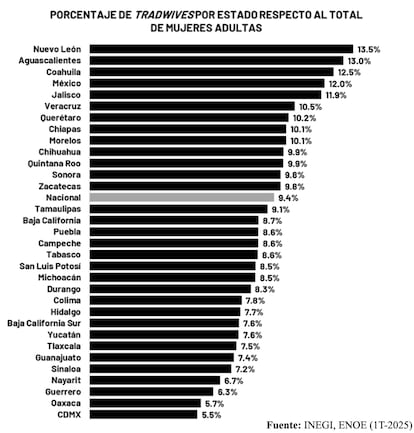

The results show that, regardless of what circulates online, in Mexico the tradwives They are few and their proportion has not changed substantially. Only 9% of adult women meet this profile, practically the same percentage as twenty years ago, when they represented 11%.

Contrary to the image spread on the networks, the tradwives Mexican women usually do not belong to the richest or poorest strata, but rather to intermediate income levels. The majority, in fact, are part of families in situations of vulnerability or poverty, but not extreme ones.

This is also reflected in their level of education: tradwives They are more common among women with secondary education (13%). On the other hand, among those who have a postgraduate degree or no primary education, tradwives They almost do not exist (4% or less). In the first case, because the desire to work prevails. In the second, because economic necessity dictates it.

However, this does not mean that “Sanpetrine” do not exist. They exist and they are many. Nuevo León is the state that has the most tradwives urban areas of the country (14%). And above all it stands out for having a large number of tradwives upper class. In fact, 20% of all tradwives the state’s urban areas have a bachelor’s or bachelor’s degree level, something that is clearly correlated with high income.

There are also, although to a lesser extent, the “Ladies of Las Lomas”. In Mexico City there are very few tradwives (only 6% of adult women are), but unlike other states, few tradwives Existing Chilangas appear to have a higher income level than the rest of the country. 25% of tradwives in Mexico City have a bachelor’s or postgraduate diploma, a fact that is strongly correlated with a better income. These are women with high purchasing power who have invested a lot of time and resources in their professional training, but who are not looking to enter the job market. Twenty years ago, only 11%. tradwives from Mexico City they had a higher education. Sinaloa is the only state where a greater percentage of tradwives They have a university degree (26%).

One of the most frequent doubts in the networks is whether the lifestyle tradwife is on the rise, especially among young women. The data does not support this idea. Over the past two decades, the percentage of tradwives 35 years or younger showed no significant changes.

Therefore, rather than constituting a return to conservatism, the phenomenon tradwife In Mexico, a tension emerges between an aspirational idea built on social networks, in this case that of a rich woman who doesn’t have to work, and a reality in which the country is moving, almost entirely, towards higher levels of economic autonomy and access to education for women.

This coexistence of opposing trends demonstrates that Mexico does not follow a single cultural itinerary, but follows several at the same time. And that, even among women who have decided to dedicate themselves to the home, the possession of a degree is increasingly widespread, which opens the doors to being tradwife be only temporary.