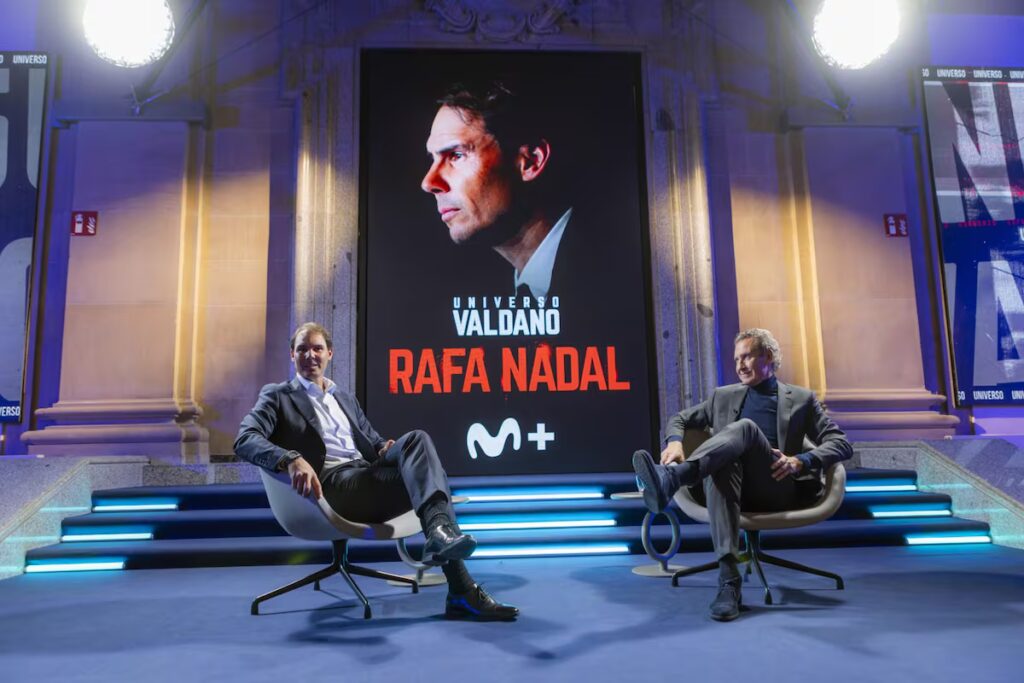

“I became world champion in Mexico the year you were born,” says Jorge Valdano. I couldn’t see it, Rafa Nadal apologizes. A former footballer, a legendary Argentine striker for decades, interviews a former tennis player who is still trying out his retirement suit: Rafael Nadal, 22 Slams, 14 Roland Garros. Valdano Universethe Movistar program brought together the public and media last Thursday the 20th at the Espacio Telefónica on Gran Vía in Madrid. Queue to enter, electric expectation. Just cold on the street, warm from the clay and the June sun inside.

One of the juiciest moments of the interview has to do, this is how Valdano brings it, with the Nadal archetype, the reductionist characteristics of his game: the devoted, selfless, fighting, courageous, resistant boy with a hellish psychology for his opponent, a man strong as a rock. But isn’t tennis a sport of exquisite quality, which sometimes a mountain of muscles solves, at the decisive moment, with a very delicate movement of the wrist? Hasn’t Nadal sometimes felt, Valdano asks, a little less appreciated for his tennis, for his tennis quality? Nadal smiles. He quotes the quote, without a clear father, that success is 99% hard work and 1% talent. To say that he worked a lot, he trained a lot, he made enormous efforts, but what he did, someone else can do. That is to say: if success belongs to those who train their body the most, we can all train it.

José Luis Cuerda told a relevant story. One day a woman, pointing to César González Ruano, asked her partner what that man did there every night. “Write,” he replied. “Come on, and this is what you live for?” “Woman, if we lived like this we would all write.”

Nadal basically defends something like that in the interview. It makes a certain impression to see one of the best tennis players in history defend his qualities, his natural talent. But Valdano is right. There is a narrow imaginary of flashing lights in which the idea that Nadal is a great athlete has been consolidated. Instead of playing with the racket, play with the bread. “You can train as many hours as you want, but if the guide It doesn’t go where you want… You can’t stay at the top level without the quality of tennis, that’s obvious.” And without possibilities, he says: without nature rewarding you with a certain physique or certain characteristics. “Nature has been generous with me,” he acknowledges.

The legend speaks, of Lamine Yamal – he takes the name Valdano – and of young people like him who exploit their talent early on a global level, of the importance of passion. On the importance of having explored what your passion is before, as children. And have fun. “Surround yourself with people who really help you. Let them tell you things that successful people don’t want to hear. Everyone wants to see you, everyone wants to hear from you. But you have to find a point in real life, a place to return to.” “I did,” he recalls, “everything any teenager can do in their life.”

And Nadal defends, at Rafa, a strong argument: Manacor, his lifelong friends, his lifelong neighbors, what binds him to a place that does not threaten to blind him like the lights of New York, Monaco or Shanghai, where everyone knows Nadal. Also in Manacor, but so much so that it is one more. “I always come home,” he takes a sip of water and clears his throat. And it abounds: being born in a small town, and on an island, helped him. Because life there, he says, “doesn’t go that fast”.

“I didn’t make big sacrifices,” he says, “what I made were big efforts. I didn’t become obsessed. I was a competitor and when I couldn’t compete at the level I knew I should be competing at, I left. I liked what I did. I didn’t retire because I was tired of what I was doing. not even to be without the necessary motivation. I retired because my body couldn’t take it anymore. But I was still happy doing what I did.”

Success, Valdano wonders. Nadal is sincere. “The success, the Davis Cup point in Seville, that madness in 2004 at 17 years old, I experienced it naturally.” Because, let’s remember, before being a champion of tournaments around the world, he was already a champion since he was a child. “I had already been champion in Mallorca, I was already champion in the Balearics. My evolution has always been linked to success, so when professional success came I was already prepared.”

Tennis, says Nadal, is a repetitive sport. “In football you can do something brilliant during the whole match, do nothing more and resolve the match,” he says. In tennis, if you create three geniuses, you can lose a match. “In tennis it is not possible to disappear”. Rafa Nadal, in fact, will never disappear.