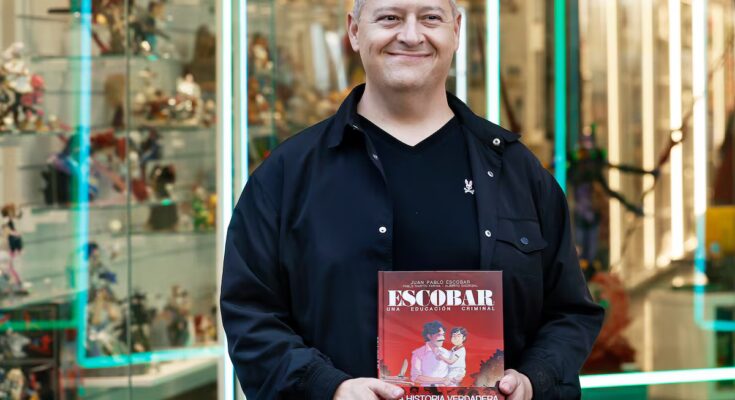

Juan Pablo Escobar (Medellín, 48 years old) has perhaps one of the most difficult legacies to manage. The legacy of his father, Pablo Escobar, marked by violence and the frightening figure of 5,500 deaths during the rise of the Medellín cartel, between 1989 and 1993. Accompanying him in his name and surname, in films, series and books. In his quest to confront his past and tell his side of the story, he now turns to the comic book format. Escobar, a criminal educationby the Catalan publisher Norma, faces his childhood in an atmosphere of fear and secrecy. “I am committed to dispelling the myth of those who see my father as a successful person, especially among young people,” he explained on Wednesday, during the presentation of the book accompanied by Pablo Martín Farina and Alberto Madrigal, responsible for the screenplay and drawing.

Architect, industrial designer and pacifist, according to him Escobar chose the comic format as a different way of telling his past and a way to get closer to youth. “As much as I am a writer, I had never talked so much about myself. I had to learn how to write a comic, I didn’t know that each scene had its own script,” said the author, who also composed some of his works under the pseudonym Juan Sebastián Marroquín. The idea, he explained, was born during the pandemic, in a moment of personal reflection on how to tell his story “with the greatest possible respect” for the victims and “without apologizing” for the universe of drugs and violence. “I raise awareness, Netflix glorifies it,” he criticized.

The book focuses on his childhood: the years in which he lived surrounded by hitmen, who also acted as babysitters, with various bodyguards and anxiety as a constant in a life under countless threats. “There was no possibility of dreaming. Life was permanently at risk. I created a very deep and very intense relationship with my caregivers,” she recalled.

For narrative purposes, he explained, he chose to reduce the number of characters involved, while always maintaining the truthfulness of the story. One of those health workers, he confessed, is still alive and has read the book. “It was interesting to see his reaction. In relation to the world, he’s dead, but he’s still alive,” he noted.

The routine marked by violence is described without the explicit character of Pablo Escobar, although he is always omnipresent. It’s only on the cover, which shows an embrace between them, and in the last 15 pages “I didn’t want my father to be the protagonist of this story, because it’s my story,” he insisted. Behind thousands of victims, orphans, widows and those who were about to put the Colombian state in check with its war to avoid extradition to the United States, however, the shadow of the mind is always present.

The author recognizes the contradiction of growing up in fear and privilege resulting from the incalculable wealth generated by drug trafficking. “It didn’t make me happy to be happy with the luck of a bad life. It didn’t make me proud; it created a mark for me,” he confessed. In recent years, Escobar has publicly apologized to the families who were victims of his father’s violence and defends the need to address drug trafficking from another perspective. “Colombia has not been able to overcome this problem. It is a very sad story. It is a war in which no one has won and no one will win. It is a public health problem, not a safety problem. Prohibition is not the right way either,” he said.

Escobar’s son, with his book, tries to elaborate the impacts and contradictions of being the son of who he is. While acknowledging the complexity of the character, he recognizes him as a father present in his absence. He remembers the letters he received weekly from the boss, messages in which his father asked him not to be frightened by the explosions and shootings. “He texted me, ‘You’re going to hear a lot of explosions this week, but I’m fine,’” he explained. Ironically, it was because of one of these communication attempts that the police tracked down his location on December 2, 1993, finally finding him in a house in western Medellín and where he was shot several times as he tried to flee.

He also remembers the lesson his father gave him when he was twelve, when he first told him about cocaine addiction. “It’s a paradox: he didn’t give me the best example, but he gave me values,” he reflected. The intention, according to him, in writing the comic is not to reconcile with the myth, but to break it. “I would rather die than repeat my father’s story,” he concluded.