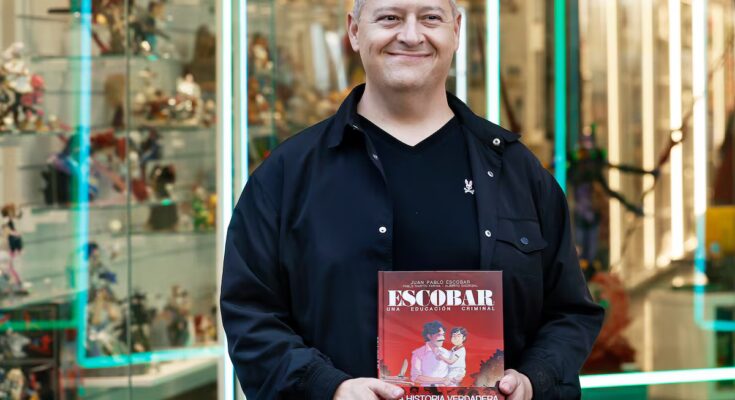

Juan Pablo Escobar, 48 years old, carries with him perhaps one of the most difficult legacies to face: that of his father, Pablo Escobar. It’s a legacy marked by violence and the staggering 5,500 deaths recorded during the peak of the Medellín cartel between 1989 and 1993. The weight of the name follows it – in films, TV series and books. In an effort to face his past and tell his side of the story, he now turns to comics. Escobar, a criminal education (in English, Escobar: a criminal education), published by the Catalan publisher Norma, explores his childhood in an atmosphere of fear and secrecy. “My goal is to dispel the myth of those who see my father as a successful man, especially among young people,” he explained on Wednesday during the presentation of the book, together with Pablo Martín Farina and Alberto Madrigal, responsible for the screenplay and illustrations.

Escobar, an architect, industrial designer and pacifist, says he chose the comic book format as a different way to tell his past and connect with young people. “Even though I am a writer, I had never talked so much about myself. I had to learn how to write a comic; I didn’t know that each scene had its own script,” said the author, who also produced some of his works under the pseudonym Juan Sebastián Marroquín. The idea, he explained, was born during the Covid-19 pandemic, a moment of personal reflection on how to tell his story “with the utmost respect” for the victims and “without glorifying” the world of drugs and violence. “I raise awareness, Netflix glorifies it,” he said.

The comic focuses on his childhood: the years he lived surrounded by hitmen who also acted as babysitters, with various bodyguards and the ever-present anxiety of a life surrounded by countless dangers. “There was no room to dream. Life was constantly in danger. I developed a very deep and intense relationship with my guardians,” he recalled.

For narrative purposes, he explained, he chose to reduce the number of characters involved, while always maintaining the truthfulness of the story. One of those custodians, he confessed, is still alive and has read the comic. “It was interesting to see his reaction. In relation to the world, he’s dead, but he’s still alive,” he noted.

The way violence shaped his life is described without explicitly including the character of Pablo Escobar, despite his omnipresence at all times. It appears only on the cover, showing an embrace between them, and on the last 15 pages. “I didn’t want my father to be the protagonist of this story, because it’s my story,” he insisted. Yet the shadow of the mind behind thousands of victims, orphans, widows and the man who almost brought the Colombian state to its knees with his war to avoid extradition to the United States, is ever present.

The author recognizes the contradiction of growing up in fear and the privilege resulting from the immense wealth generated by drug trafficking. “It didn’t make me happy to be happy with the luck of a bad life. It didn’t make me proud; it left a mark on me,” he admitted. In recent years, Escobar has publicly apologized to the families of his father’s victims and argues that drug trafficking needs to be approached from a different perspective. “Colombia hasn’t been able to overcome this problem at all. It’s a very sad story. It’s a war in which no one has won, and no one ever will. It’s a public health issue, not a safety issue. Prohibition isn’t the right way either,” he said.

With his book, Escobar’s son tries to elaborate the impact and contradictions of being who he is. While recognizing the complexity of her father’s character, she remembers him as a figure present even in his absence. He remembers the letters he received weekly from the cartel boss, messages in which his father urged him not to be frightened by the explosions and gunfire. “He texted me, ‘You’re going to hear a lot of explosions this week, but I’m fine,’” he explained. Ironically, it was one of those communication attempts that allowed police to trace his whereabouts on December 2, 1993, finally finding him in a house in western Medellín, where he was shot several times as he tried to flee.

He also remembers the lesson his father gave him at age 12, when he first told him about cocaine addiction. “It’s a paradox: He didn’t set the best example, but he instilled values in me,” he reflected. His intention in writing the comic, he says, is not to reconcile with the myth, but to break it. “I would rather die than repeat my father’s story,” he concluded.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition