Rafa Nadal “is bald, he is no longer what he was”. It is the criticism of Alexander Bublik, number 33 in the ATP ranking. And, it seems, a constant murmur online every time a recent image of the tennis player appears following his retirement from the public eye. The last one was saved by haters on October 7th on the occasion of the so-called World Baldness Day. Criticism is divided into two poles: on the one hand those who say that with the money they have they should have done their hair; on the other those who found it horrendous that he left his hair as it was and asked for it to be shaved completely. Few, if any, were those who claimed the right of every man to follow the path of baldness in his own way. Without considering it a problem to which a solution must be found.

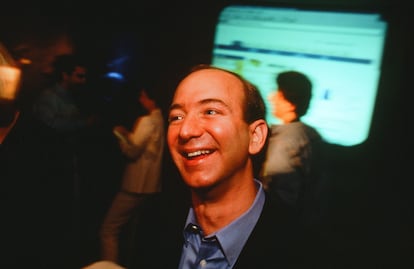

American comedian and screenwriter Josh Gondelman recently linked this aesthetic pressure to incipient social polarization in an article titled There is nothing more attractive than not worrying about baldness for the American edition of the magazine GQ. “Men may be bald or have hair, but the process of going bald itself has become taboo. Our culture no longer allows for the middle ground: the classic bald spot,” he wrote. As an example, he cited the two great technology moguls of the United States: Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. The former opted for all kinds of treatments to recover his hair, while the latter preferred to shave completely and embrace the typical aesthetic of the bald and muscular man. “We cannot forget that there are many more options than just these two opposites. Baldness is not binary, it is a spectrum. I am not completely bald and may never be and this discovery should not cause me any kind of shame,” Gondelman wrote.

Still, with the expansion of cheaper and more accessible hair treatments, Gondelman lamented that many men end up choosing one of the two extremes. This creates an increasingly homogeneous widespread panorama in which every hint of individuality is highlighted. “I don’t agree that baldness, like an extra kilo, are things that must exist as a system solvealthough they can be treated medically, especially, in the latter case, if it is a health problem,” says Daniel García, cultural and lifestyle journalist, 45. “There is the paradox that we are asked to make everything seem easy: style effortlesslya rested face, being 35 years old forever and in general the natural thing, when everything costs dearly. And not just money, but very slave-like medical treatments, with a lot of margin for error and sometimes requiring an operating room, which are the antithesis of what is natural. The counter-revolution of the truly natural appearance of the face, body and hair is missing. In other words, accept yourself, which does not mean being careless, unhealthy, or falling into decadence. Not to mention the homogenization that means we all wear the same teeth and hair and take the same drugs to lose weight.”

Photographer Javier Talavera reflects with great humor on this aesthetic standardization in his photography book Not all bald people are Javier Talavera (La Mosca Edizioni, 2025). Being bald, he was very interested in highlighting the uniformity that was created among all the men who resorted to shaving their hair and growing beards. “My friends often confused me with other bald people at concerts or festivals. They took pictures of us together and played who’s who. From that joke I decided to make a counter and turn it into a defense,” he says. To do this, he began looking for a large group of bald men with a similar aesthetic to those he could portray, but a health problem prevented him from making it happen. So he decided to recreate 135 different versions of himself with artificial intelligence. The success of the book encouraged him to relaunch the photographic project and is already bringing together many men with his same characteristics. “I shave because it’s much easier, the binary is always much more comfortable. If you go beyond it, you fight against a terrible canon. The man who does nothing about his baldness is associated with the figure of the vagabond, the sick person or the madman”, he adds.

Luis Salas Miquel, author of the novel Who we are (Lunwerg, 2025) and fashion expert, he has never had a choice: his alopecia prevents him from adapting to that canon. “It’s called Alopecia Areata, bald patches appear and disappear all over the head, with the good thing that, when the inflammation stops, the hair returns. There is a medicine to cure it, but it’s not even Fierabrás balm. The hair does come out, little by little, but as it wants and without uniformity. I have a bald patch on the right side that every time I see it I think: ‘Damn, there are always insecurities’. But it’s really just the way I am. This is something that will always be with me.

Salas recognizes that at another time he felt that pressure as an obligation and suffered a lot trying to integrate. “Either you shave it or you leave it on for a long time to camouflage bald patches or areas where there is less hair density. And you do it so that they look at you as little as possible. When I started, one of the treatments was topical, it caused abrasions on the scalp and it itched so much that it didn’t even let me sleep. My glands also swollen and it was precisely because I wanted to stop being on the sidelines.”

Salas also points out that hair prosthetics do not work in all cases, as in his, and that, although they have lowered the price, it now fluctuates between 2,500 and 8,000 euros, and for many the average salary of a Spaniard is still difficult to afford. “It should be completely legal for it to be an option that people don’t even consider. To accept bodies in all their diversity we need to embrace these differences. We need to be more than just photocopies. Making visible helps to normalize, right? Maybe it’s time for more models with alopecia to enter Paris Fashion Week,” she proposes. Precisely to help in this work of visibility, Luis Mariano Seijas decided years ago to create his YouTube channel, Calvos Guapos, in which he delves into and gives voice to all types of alopecia. From there, he criticizes the fact that current references, rather than liberating, can actually impose a lot of pressure.

The horseshoe, the final frontier

On the one hand, Seijas regrets that many men become obsessed with muscularity, as Jeff Bezos himself did, when they shave their heads to resemble icons such as Dwayne Johnson, Jason Statham or Vin Diesel, who since the nineties have made the zero point of the razor another example of their strength and virility. “When you go bald, three paths open up: avoidance, acceptance and compensation. Becoming hypermuscular can often mean compensating for something you think you’ve lost,” he explains. Many other prejudices, he argues, carry over into mid-2025 with the classic “horseshoe” cut: the bald area on top with hair on the sides caused by androgenetic alopecia. In another era it had large and virile defenders in Hollywood, from Sean Connery, Ed Harris to Woody Harrelson, and in Spain, starting with José Luis Lopez Vázquez and ending with Luis Tosar or Javier Cámara. But today it has become the most hated cut, associated with very old and unfashionable men. “If a young man still has difficulty shaving his head, imagine the horseshoe. The most infamous type of bald head!”

Although he youtuber He recognizes that there are still many young, or not so old, references to breaking the horseshoe taboo, and also argues that the most important thing is to start losing fear. On his channel he encourages all men, regardless of their degree of baldness, to stop shaving and let their hair grow, even for a few weeks. “That’s how you realize it’s no big deal. Eventually you get used to it and it’s very liberating to notice that in some places you have hair and in others you don’t. Nothing happens. There are many who end up becoming slaves to shaving without really wanting to,” he explains.

Seijas, specifically, did this for 12 weeks and found that while she wasn’t looking for that cut at the time, she didn’t rule out wearing it in the future or at specific times. “There are endless ways to experience the baldness journey. Why shouldn’t I be able to wear it the way I want? Shaving is usually a tool to regain control, but it doesn’t have to be a permanent style. You can go to the hairdresser even if you’re bald. If you shave, leave it because you really want it and it’s part of your identity,” he adds.

Luis Salas also agrees with the same argument. “If you do it because you look better, it makes a lot of sense. But if you already do everything to avoid being looked at in the street or said something, the blame lies with this society of hatred in which we live and where it is very difficult to exist on the margins. People do not understand that, in the process of falling, the management of each person must be free”, he defends. Until this message sinks in, Salas leaves at least one piece of advice to all passersby: “When someone has something that makes them different, we make them feel bad with looks or comments. You can do it without malice, but the other five who looked at them that afternoon also did it without malice.”