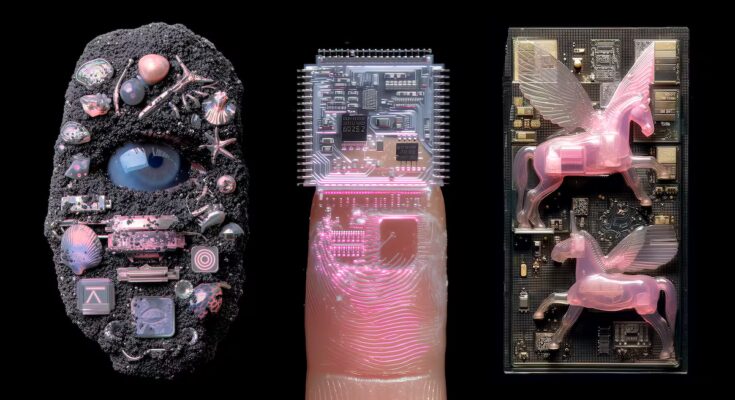

The discovery occurred thanks to an online exploration. Artist Xavier Cardona recalls that the first time he learned about artificial intelligence integrated into creation was in 2019 when, like a digger, he was scrolling through endless Reddit threads. In those years the community experimenting with these tools was scarce. “Everything was very embryonic,” Cardona says. He had been working in 3D for more than a decade, but felt the medium wasn’t up to par. On the Internet, he discovered nascent groups playing with rudimentary algorithms like Google Colab. “Even though it was a bit precarious and boring, all this obsessed me,” says Cardona, who together with his brother Daniel forms Boldtron, an artistic duo specializing in 3D, virtual reality and artificial intelligence.

The fact that large language models (LLMs) are used to create works of art means for some that current technology has conquered central concepts used in philosophy to define human nature: logos and creativity. Others, such as contemporary digital artists, see multiple possibilities for creation in it.

For audiovisual artist Ana Esteve Reig, the use of artificial intelligence did not represent a shortcut, but rather a different, and often arduous, way of producing images. It started in the summer of 2023, motivated by interest in video generation. At the beginning there were many limitations, he says. The clips were short-lived and failures were frequent.

Since then, tools have evolved to allow for camera movements, lip-syncing and sound, but for this creator the process remains tedious. “You have to fight the machine to get what you want,” he says. The results, while increasingly fluid, still require constant vigilance on the part of the artist.

Fill in the blanks

Esteve Reig conceives it as a tool to fill in the blanks: scenes that are beyond his reach. He states that “travelling, being there, knowing” continues to be essential and what AI offers him is another way of thinking about the image, an intermediate territory between the real and the virtual. “It’s not 3D, but it’s not real either. It’s kind of stupid.”

In his work, where identity and visual stereotypes take center stage, artificial intelligence also becomes a field of criticism. Esteve found that models tend to reproduce prejudices: “If you ask for a woman, you always get a white, sexualized, very standardized character. They are traces of how she was formed.” Faced with this, he learned to form his models with his own references.

“There’s a belief that with one click you have it, but that’s not the case. Unless you’re happy with the first thing the machine gives you.” His work involves hours of testing, mixing and editing: “For a five-minute video, it can take 15 days.” You then refine the fragments in an editing program, where you fix the mistakes and recreate what went wrong. His exploration is specific: “I use it when it makes sense within the project.” Artificial intelligence, he says, does not replace the human gesture, but rather amplifies it. “A painter will not stop painting because of artificial intelligence. The pleasure of picking up the brush is not replaced.”

Elena Pérez, creator of the Remembering Orion project, imagines impossible worlds and lost theories. “Before, I spent months trying to produce something like this,” says the artist, who specializes in digital design. “Now I can explore 20 worlds in an afternoon and none of them are the same.”

He comments that, while retaining the characteristics of his first pieces (color palettes, atmospheres and a gaze between the cosmic and the intimate), his way of producing changes according to the progress of technology. “Before working with requires (instructions given to an AI). Now I barely write: I give visual references, my own or royalty-free images, and let the AI build from that.”

An extended debate

There has been no shortage of criticism from the sector. In 2024, a group of associations of Spanish authors, artists and cultural workers presented a manifesto to the government to denounce the use of artificial intelligence in creation. They asked for permission and compensation for the use of their works, as well as transparency about how their content is used to train models. “The position remains exactly the same,” says Eva Moraga, lawyer and spokesperson for the signatory organizations, a year later.

The organizations warned that the products unfairly compete with their works, discourage creation, and put their professions and incomes at risk. “They meet all the criteria of unfair competition: they build on the work of others, replicate it and place it in the same market.”

Pérez, an artist trained in Fine Arts, adopts a conciliatory position in the face of this controversy. “I understand those who don’t want to use it because they feel the craftsmanship has been lost, but this has happened with all technological revolutions. Resisting is like trying to stop something inevitable.” The key. he argues, is about using the tool as an ally. “Not everyone gets results, just as not everyone who has a camera is a photographer. What turns something into art is direction, the human gaze.”

Can we imagine with machines?

A recent publication in a magazine Nature recalls the study conducted by researchers Amy Ding, of the Emylon Business School in Lyon, France, and Shibo Li, of Indiana University in Bloomington, who tested a version of ChatGPT (ChatGPT-4). The scientists found that he would still have difficulty with flexible and creative thinking done on his own.

For the Finnish theorist Jussi Parikka all imagination is collective. No idea, not even an artistic one, is born in solitude. “What if we had always imagined with machines?” he asks. From brushes to requireseach tool expanded the concepts. In this sense, he comments, we don’t imagine alone and machines don’t imagine alone, we do it with them. His presence and companionship, he says, are not just in the cloud, but also in matter. As explained in Operational images (Caja Negra, 2025), “Artificial intelligence is in data centers, in submarine cables, in servers built in peripheral regions. Data rematerializes the world,” he argues.

For the essayist Lluís Nacenta we find ourselves in a founding moment, comparable to the birth of cinema. “At first it was just a technology.” Although, he states, there is no articulated artistic language yet, but only an exploration of what it could become.

Nacenta, who curated the exhibition AI: Artificial Intelligence at the Center for Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (CCCB), agrees that generative tools alone are not sufficient to produce a work. “Technology does not create art alone. Culture, tradition, the public, the market, the entire ecosystem of creation do it.” When faced with those who mistrust he has a sympathetic position. He doesn’t consider the resistance of some artists retrograde. Rather, it is argued that, in many cases, it is a form of ethical defense. “It’s not about rejecting technology, but about opposing abuses in its use.”

Authorship and the instrument

Who signs a work produced in part by a machine trained with other people’s data? For Nacenta, the problem of paternity is not new. The previous avant-gardes dealt with it first, “the collageconceptual art, electronic music and samplingFor him, artificial intelligence does not destroy the traditional idea of the author, but redefines it.

According to José Luis Ramos, artistic director of the Matadero cultural center, artificial intelligence is an extension of the creative repertoire. However, he introduces a nuance that he considers fundamental: transparency. For him, the public must know whether a work was created or assisted by artificial intelligence. “It is essential that viewers are aware of this. Art must continue to be a space of freedom, and artificial intelligence, if it can make a contribution, will have to do so from there,” he argues.

Digital “Pharmakon”.

Artificial intelligence does not run the risk of taking away meaning from the creative act, according to Parikka. He prefers to distinguish between superficial uses and others, where the machine becomes a critical lens of its time, like art from its foundations. In the foreseeable future it will no longer make sense to talk about art and artificial intelligence. It will simply be a kind of technological element integrated into all creative areas.

The really important thing will be to learn to live with his ambivalence, he says, a sort of “pharmakon digitalis”, a Greek term that refers to a poison and a cure at the same time. “AI is a little toxic, but it can also be healing. And we will have to live with this.”