The annual climate summit, COP30, which this year will be held in the Amazonian city of Belém (Brazil), officially began this Monday, although a previous meeting was held last Thursday and Friday in which several dozen prime ministers and presidents participated. At 29 degrees and with 73% humidity in the streets, this meeting began in which for two weeks countries will try to agree on a common approach to tackle the climate crisis in a complicated international political moment from which the fight against warming is by no means isolated.

“It is time to impose a new defeat on the deniers,” proclaimed Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva at the opening of the summit. In his speech he warned against misinformation and algorithms that attack science. Furthermore, he defended multilateralism in this difficult international moment.

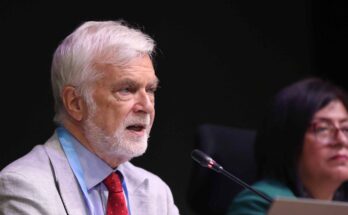

“Your task here is not to fight among yourselves, but to fight together against this climate crisis,” Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UN climate area, told participants at the same opening event. “Multilateralism is definitely the right path,” added André Corrêa do Lago, the Brazilian diplomat who is chairing this COP30. “Urgency is the distinctive element of this mission,” underlined Correa do Lago, referring to the fight against global warming. “That element so present, as we saw with great sadness this week in Paraná and the Philippines, and two weeks ago in Jamaica,” in reference to the most recent tornadoes, typhoons and hurricanes.

Lula also referred to these disasters that fuel climate change, drawing a parallel between the colossal logistical challenges of hosting the summit in the Amazon and the fight against the climate emergency. “It would have been simpler to celebrate it in a city without problems. But we decided to demonstrate that, when there is political will and commitment to the truth, nothing is impossible.” He added: “To those who wage war, I say that it is much cheaper to spend 1.3 billion on ending the climate problem than 2.7 billion on wars, as they did last year.”

The Belém event is the thirtieth since the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was agreed at the Rio de Janeiro summit in 1992. This convention is the one that has guided the steps of the international fight against climate change under the auspices of the United Nations for the last three decades. In this context, in December 2015, the Paris Agreement was born, the most ambitious of the climate pacts implemented so far, which this year celebrates its tenth anniversary in a complicated international context.

The Brazilian government’s predictions before the start of the summit were that around 170 countries would participate in the negotiations. The United States informed the UN a few days ago that they will not send a delegation to Belém, although it could land at any time because, despite Donald Trump having withdrawn his country from the Paris Agreement, it remains a member of the framework convention. The participation of the United States in the latest environmental meetings within the United Nations has not been particularly positive for the advancement of international treaties: in October it threatened countries that supported a tax on carbon dioxide emissions from the international maritime sector with tariffs and sanctions. In August he actively contributed to the failure to agree on a treaty that would limit plastic production to stop this pollution. And a few days ago the US government asked the UN to clearly declare in writing its decision to slam the door on the fight against climate change in the report analyzing countries’ plans to reduce emissions.

Added to these blows by the Trump administration is a wave of brakes on climate and environmental policies in the EU. And the advance of far-right denialism in the governments of many countries. This is the context in which a climate summit will take place that does not have a clear objective like other recent events, beyond the fact that it will be held in the Amazon, one of the largest sinks on the planet, also threatened by global warming.

Last year’s summit, in Baku, Azerbaijan, focused on the financing that richer countries should provide to those with fewer resources to fight and adapt to climate change. And in Dubai in 2023, for the first time in these three decades of white-on-black negotiations, he indicated the main culprits of this crisis, fossil fuels, and urged their progressive abandonment.

However, the meeting in Belém will be dominated by the failure to comply with one of the obligations of the Paris Agreement. The nearly 200 countries that sign up to this treaty must periodically submit their own emissions reduction plans (known by the acronym NDC), in which they self-impose specific objectives. These commitments must lead to a temperature increase of no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and, as far as possible, to 1.5 (even if the latter barrier is assumed to fall in the next decade and the only alternative is that this excess of 1.5 is only temporary).

In February 2025 all countries were supposed to present their new plans, with targets for 2035. Virtually no one respected them. The UN then asked governments to do so before September 30th. But only six dozen have complied with this new extension, which has prevented scientists from providing the United Nations with a good analysis of what the new reduction targets mean. In recent days, the pace of NDC submissions has increased and this Monday, 108 national plans are already on the UN register.

Although it was not possible to make a precise assessment, what is known is that the aim is not to ensure that the temperature increase remains within the safety margins, between those 2 and 1.5 degrees. And one of the most contentious points of debate is how to address this gap between what should be done and what different governments envisage. The other gap to be filled is that of financing for developing countries, which has also suffered a serious blow due to the withdrawal of the United States from climate forums.

Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asian Society Policy Institute, sees this Belém summit as a “collective graduation ceremony for the Global South”. For the withdrawal of the United States and the hesitations of the European Union, but also for the step forward represented by the new climate plan that China presented at the end of September, where for the first time it commits to concretely reducing its emissions. China is also a world leader in the installation of renewable energy and the production and sale of electric cars.

In a letter before the start of the summit, Corrêa do Lago combined satisfaction with the progress made with the urgency of urging countries to have more ambition and step up the accelerator. The diplomat argued that the climate transition is already an irreversible trend and a driver of sustainable development and that “the Paris Agreement is working”. Now, he stresses, “the challenge is to accelerate its implementation to keep the 1.5 degrees Celsius target within reach, while strengthening resilience to the growing impacts (of global warming).”

The letter from the Brazilian ambassador praises the Chinese leadership, stating that “the climate transition is the trend of our time, as underlined by Chinese President Xi Jinping”. This mention – the only name next to Lula’s – is significant at a time when the American Donald Trump proclaims that global warming is a farce.

“In a certain sense, the decline in enthusiasm from the Global North shows that the Global South is moving forward,” Corrêa do Lago told reporters in Belém on Sunday. “It’s not something new, it’s been brewing for years, but it hasn’t had the visibility it has now,” he added in statements reported by the Reuters agency.

In addition to accelerating the implementation of the Paris Agreement, seeking to establish roadmaps for aspects such as adapting to climate change or abandoning fossil fuels, Brazil’s priorities for this summit are to strengthen multilateralism and “connect the climate regime to people’s lives and the real economy”. Hence his idea to create an investment fund that serves to protect tropical forests and pay those who protect them with their sustainable lifestyle.