His fate was oblivion. After being shot in the Hradischko concentration camp, the bodies of Basque Anjel Lekuona and six other Spaniards ended up in a civilian crematorium in Prague. Once cremated, their remains were to be used as compost: the Nazis wanted no trace to remain. But the director of the Strašnice furnaces, in 1945, kept more than 2,000 urns, including those of republicans exiled by fascism. When World War II ended, no one claimed his ashes. Nearly 80 years passed before relatives knew where they were. The discovery was the result of an investigation initiated by a historian and nephew of Lekuona, which can be seen in the documentary Popel and which opens today, Friday in Bilbao.

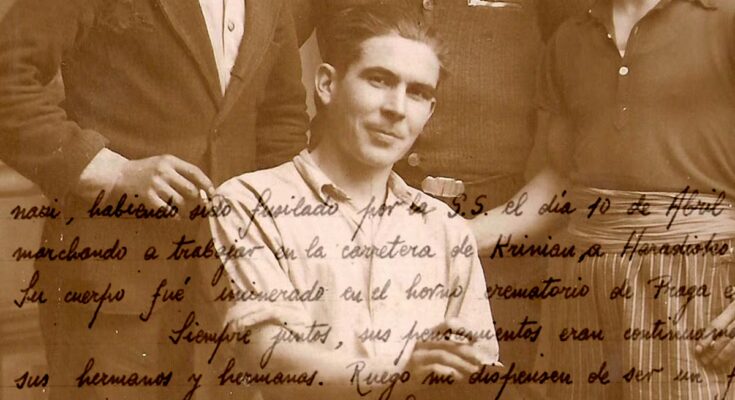

As if it were a fiction, it all began with a forgotten letter. The mother of Antón Gandarias (Gernika, 64), Anjel Lekuona’s nephew, kept it hidden on the bedside table. “During the Franco regime,” Gandarias recalls, “there were no things that indicated that you had an older brother who had fought for the Republic and who had fled.” It was only with Franco’s death that the drawer was opened. Handwritten by a companion of his uncle who survived the Hradischko camp, it chronicled their journey through Nazi Germany until April 10, 1945, when Lekuona was murdered by the SS. “That letter is kilometer zero of this investigation”, underlines Gandarias on the phone with EL PAÍS during the preview of Popel. However, despite having read it “countless times”, there was one detail that went unnoticed.

After specifying the place and date of the execution, you might read: “He was cremated in the Prague crematorium.” This detail became important when the historian Unai Eguia was looking for another republican deportee, Enric Moner, whose identity was impersonated by Enric Marco, the protagonist of the book. The impostor—. Meeting Gandarias, they discovered that both Lekuona and Moner had followed the same route: from deportation to death.

Popel It is made up of several intertwined stories, told in different languages: Spanish, Basque, French, German and Czech, the language of the title meaning “ash”. “The great challenge of this documentary”, explains its director, Oier Plaza (Gernika, 41 years old), “was to organize an investigation that begins in Bilbao and ends in Prague, with many historical leaps”. In Bizkaia “many people know the story of Lekuona. When they told me (three years ago) that they believed they had found him in Prague, I went there with relatives.” To the largest crematorium in Europe. Strašnice became the center of the feature film. The idea was born Popel.

It was there that, in an act of disobedience to the Gestapo itself, the director of the facility, František Suchý, and his son, who bore the same name, risked their lives to hide the ashes of the victims. “What humanity that man had,” explains Gandarias, “who had no relationship with these people, was absolutely unknown.” “In the Czech Republic, no one knows where Busturia is,” continues Lekuona’s nephew. Even so, in Suchý’s cremation books first and last name, date of birth and place appear: Busturia. “This is appreciated,” Gandarias says emotionally.

The documentary puts the viewer in the shoes of those people who lost their relatives 80 years ago, says Oier Plaza: “It is thought that these wounds are no longer present, but in reality they are still very much on the surface.” Popel It is the result of a series of “small good deeds and coincidences”, explains the director on the phone from his home in the Basque Country, “and also of an exercise in memory”. “If Gregoire Uranga had not written that letter; if František Suchý – father and son – had not turned the soot into ash; or if Cercas had not written that book about Marco, this would not exist.”

“It was very exciting”, recognizes the director, “to understand how every meeting with relatives and every call to the memory centers, such as those in Flossenbürg (Germany) or Pankrác (Czech Republic), integrated”. Along the way they had another surprise. “Many times they asked us: why now?” They didn’t understand how much time had passed since the end of the Second World War, and since Franco died in 1975, without anyone going looking for him. “This amnesia of memory passes from one generation to the next,” explains Plaza. “One generation suffers the war; the next grows up in silence because their parents couldn’t tell; and the third works to recover it.”

The Strašnice crematorium, where the bodies of Anjel Lekuona (Bizkaia), Enric Moner (Gerona), Antonio Medina (Granada), Pedro Raga (Tarragona), Rafael Moya (Andratx), Vicente Vila Cuenca (Valencia) and Antonio Clemente (Almería) were cremated, reveals that there are still many stories to be saved. “In our imagination we always see huge concentration camps, like Auschwitz,” says Plaza, “even though the reality is that there were hundreds of small camps where people were killed.” This dispersion, he explains, played “a joke” on the investigators: “It was normal for the bodies to be cremated in the same ovens as the concentration camps, but the one in Prague was a civil crematorium.”

There is a lot of non-existent documentation. Popel It makes up for the lack of visual evidence with an animation style that dissolves like dust and evokes the passage of time and the fragility of memory. Kote Camacho’s proposal reinforces the symbolism of the ashes that connect the protagonists.

It has been 80 years since František Suchý deceived the Nazis more than 2,000 times. In the courtyard of the mausoleum of the Strašnice crematorium – inaugurated on the anniversary of the end of the war – the ashes of six of the seven Spaniards murdered in the Hradischko labor camp in 1948 were buried – Antonio Clemente ended up in France due to confusion of nationality. They cannot be saved: the ballot boxes, made of sheet metal, will already have disintegrated, together with those of other victims of German fascism.

Since he began investigating his uncle’s whereabouts at the turn of the century, Antón Gandarias heard many times: “Do you think you’ll find anyone alive?” But it’s not about that, he clarifies: “It’s about giving a voice and a name to the victims.” “It is absolutely necessary that this story be told,” insists Lekuona’s nephew. “Now I can bring flowers to the place where my uncle is, under the sculpture of the Bitter Spring, in the Prague crematorium.” Where there are still ashes to reclaim.