Any remaining images of the Le Perthus border crossing at the end of February 1939 may serve to give you an idea of what exile means. Hundreds of thousands of Spaniards passed through there on their way to France, without having any idea of what awaited them on the other side, with their bundles, their suitcases, the blankets that protected them from the cold, their four things to reinvent themselves in an unknown place. They left their homes, family and friends, the advance of Franco’s troops pushed them to leave, to throw overboard the life they had lived until then. Approximately 465,000 people sought refuge in France during that fateful month, half were civilians and the other half military. Later many others would leave, most of them without bringing much with them, crammed into a few boats. Of those who left for the country near February, about 350,000 ended up in concentration camps. Agde, Amélie-les-Bains, Argelès-sur-Mer, Arles-sur-Tech, Le Barcarès, Bram, Brens, Gurs, Montolieu, Le Récébédou, Rieucros, Rivesaltes, Saint-Cyprien, Septfonds, Le Vernet-d’Ariège: it does no harm to repeat these names like a litany. Behind them there are some tents, low temperatures, pots in which to boil a handful of vegetables, barbed wire, shots from the guards and, inside, fear and restlessness and uncertainty. For all those who managed to survive – around 15,000 had died by July – something must have shaken inside on November 20, 1975, when the dictator Francisco Franco died.

Of the Spaniards who traveled to the neighboring country in February 1939, approximately 350,000 ended up in concentration camps.

There is no yardstick that serves to measure exile, everyone was different. Professor José-Carlos Mainer recalls, in the piece he created for an exhibition dealing with the republicans who abandoned Spain because of the war, what Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez explained in March 1977. He was 26 years old when he arrived in Mexico, he was already trying to become a poet, he had been part of the Unified Socialist Youth; The exile ended up making him a famous professor of philosophy and, in those days when Spain was trying to conquer democracy, he wrote: “Exile is a tear that never ends, a wound that never heals, a door that seems to open and never opens.” He also says it means to be “always in suspense, without touching the ground.” Once Franco died, many of those who left managed to return – some had already done so before, piecemeal – and settled again in Spain. But they certainly were like that, “without touching the ground”.

The country they found looked nothing like the one they had left during their escape some 40 years earlier. After Franco’s death many anonymous Spaniards returned, as did some of the best known. The democracy that was being built opened its doors to them, but they already bore that sign, that of exile, and continued to be somehow strangers. Neither inside nor outside, after leaving they went to other places and learned to live there, but they did so always taking with them the Spain they had left behind. In 1959, the poet Emilio Prados wrote to José Luis Cano, the critic who founded the magazine in 1947 Island, perhaps the first bridge that connected the writers who were inside with those who remained outside: “I live in Spain, with, inside, near, without, above, after, Spain”.

That Spain that those who were forced to leave brought with them had nothing to do with the Spain that the Franco regime built and left as a legacy. The poet Tomás Segovia tells it in his book I say a relevant detail: “I didn’t go into exile, they took me”. He was still a child when the war ended, so what he had before him was the future, and for this reason he observes something that is not always taken into account: “We escaped the persecutions or exclusions suffered by the vanquished in Spain,” he writes, “but also the obscurantism, isolation and dullness of the morals and sensitivity of the victors.” The victory that Franco won after the war meant precisely this, obscurantism and dulling of morale, and at the beginning of the seventies the dictatorship continued to be a dictatorship even if it abandoned, at least in part, that isolation that pushed it out of the world and from which it protected itself with that mantle of thorns that was national Catholicism.

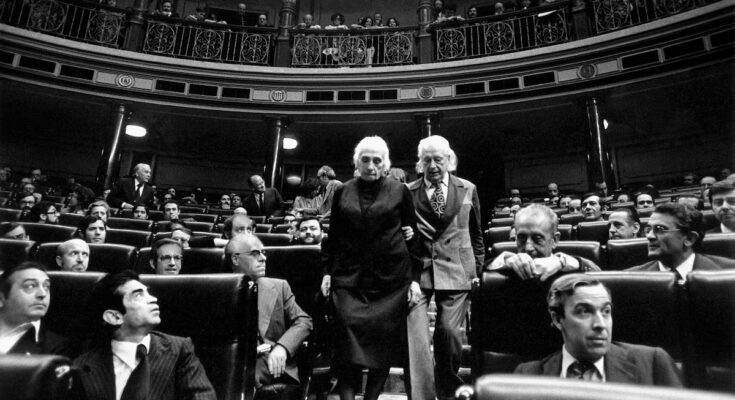

So the exiles returned, but they all suffered that short circuit, that strangeness of discovering that the Spain they had left no longer existed, and they had to find accommodation in a country that, in addition to welcoming them with open arms, was a little hostile to them, the leaden air of the regime, its servitude, still weighed too heavily. What they had clear was a single horizon, the Communist Party itself had advanced it in the 1950s and this is how Salvador de Madariaga expressed it in 1976 in his entrance speech at the Royal Spanish Academy – he had been elected in 1936 -: reconciliation. “I said I would come and cry and I’m crying. I only have one word: peace.” These were the fine print that exile brought with it, and without which it would have been impossible to build a democracy.