There are approximately 86 billion neurons in the human brain. They are the “mysterious butterflies of the soul”, as Nobel Prize winner Santiago Ramón y Cajal called them, the main cells of the nervous system, those responsible for transporting and reporting all the information that allows us to think, laugh, remember or breathe. Those butterflies They communicate, Cajal said, through “kisses,” synapses, and weave sophisticated connections to transmit the nerve impulses that build life.

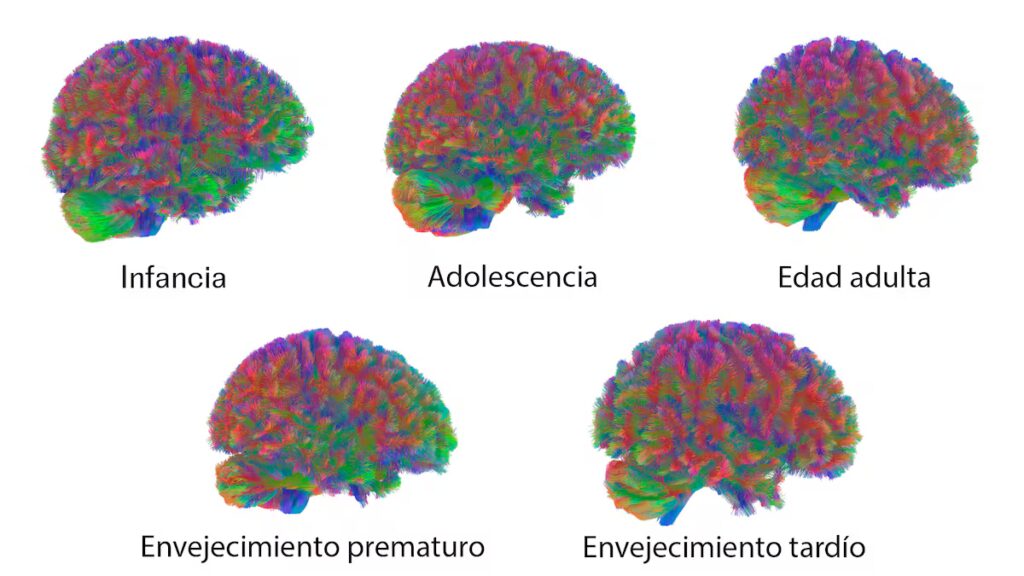

But this network of neural highways that populate the brain is not static, it changes and reconfigures itself throughout life. An investigation published Tuesday in the magazine Nature communications examined how these structures were organized over time and identified five of them age of the human brain. That is, five different periods of neural development. The authors, a group of scientists from the University of Cambridge (UK), concluded that crucial changes occur in this arrangement of neural networks around the ages of 9, 32, 66 and 83.

After comparing the brains of more than 3,800 people aged between zero and 90 through MRI mapping of neural connections, scientists discovered those four turning points that mark the beginning and end of brain age. The discovery is not insignificant, especially when you take into account that the way the brain is connected is linked to neurological, mental and neurodevelopmental disorders. “By understanding key turning points, we will be able to better understand what the brain is most vulnerable to at different ages. The more we learn about expected changes in brain connections over the course of life, the better we will be able to distinguish what is considered a healthy, typical change from signs of something related to a disease or disorder,” explains study author Alexa Mousley.

The first turning point identified by researchers dates back to about nine years ago. Until then, they argue, neuronal “network consolidation” occurs in children’s brains, where the most active synapses survive and there is an increase in gray matter (which contains neurons) and white matter (made up of connections). But at the end of this first phase of childhood – and coinciding with the onset of puberty – the brain experiences a radical change in its cognitive abilities and socio-emotional and behavioral development.

The second phase identified, which the authors call “adolescence”, goes from nine to 32 years of age. In this period of time the organization of all neuronal wiring remains more or less constant: this entire network is increasingly refined and the connections are increasingly efficient.

Now, the fact that this second phase lasts until the age of thirty does not mean that the brain is adolescent until that age, underlines Sandra Doval, professor and researcher at the International University of La Rioja. In statements to the SMC Spain portal, the researcher, who did not participate in this work, clarifies that “the study identifies when the patterns of reorganization of brain wiring change, not when the brain matures, grows old OR declines in functional terms.” In fact, the same authors recall that “the transition to adult life is influenced by cultural, historical and social factors”, which make it a change more dependent on the context than on biology.

The “strongest” change.

At 32, Cambridge researchers spot another turning point, the change in the organization of neural networks “strongest in life”, they say. This coincides with the peak of white matter maturation – other studies had already underlined that the ceiling of brain connectivity is reached in the early 1930s – and the changes in the architecture of the neuronal network, which until then occurred rapidly, slow down. This brain age is the longest phase and ranges from 32 to 66 years. “This period of network stability also corresponds to a plateau in intelligence and personality,” the authors agree.

There is another turning point at age 66, which coincides with a major change in health and cognitive abilities in high-income countries, scientists remind. In fact, it is from these ages that dementia or hypertension can begin to appear, also linked to cognitive deterioration and accelerated aging. This initial phase of aging lasts until age 83.

Around that age the last of the turning points identified by Cambridge researchers occurs, the last age of the brain. While they admit that data on this stage is limited, they note that different areas of the brain have more difficulty communicating.

Mousley says how the brain changes connections over the course of life could help “better understand related changes in cognition and behavior.” “Understanding these fluctuations could help us understand how people change over the course of life and why they are vulnerable to different disorders at different ages,” the researcher explains in an email response.

Rafael Romero García, director of the Laboratory of Neuroimaging and Brain Networks at the University of Seville, assured SMC that this is “a rigorous study” and, although it has limitations acknowledged by the authors – for example, the analysis was not separated by sex and men and women may have different developmental rates – he underlines: “It is a great contribution that has allowed us to identify inflection points in development and that could help us better understand brain alterations associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and dementia.”

They are not “hard boundaries”

This scientist, who did not participate in the study, clarifies, however, that these phases of brain maturation should not be interpreted as “hard boundaries”. “The differentiation between maturation and aging is relatively arbitrary. Furthermore, it must be taken into account that the study focuses only on brain connectivity, it does not analyze how cognitive aspects such as learning, memory, the ability to solve problems, etc. change during these phases”, he underlines.

For Sandra Doval, “the results fit very well with the known fundamental stages of neurological development and aging”, but she also underlines the limitations of the research – another example: those over 60 are probably healthier than average for their age and this may not faithfully represent typical aging – and calls for caution in interpreting the results, even if she recognizes their “scientific relevance”. “These findings do not generate direct and immediate clinical recommendations, but rather establish a valuable scientific context for future research on critical windows of preventive or therapeutic intervention at different stages of life.”