We now know that at the beginning of the 1990s in Spain the literary reader of democracy came of age. It was a maturation in step with that of the country. After three decades we had returned to being one of our European brothers and in 1992 the symbolic recognition of that normality reached a full international dimension, the night in which the flight of an arrow lit up the Olympic cauldron. Literature has not been excluded from the change. That cultural process is what I try to outline here based on the list of the 50 best books of the last half century.

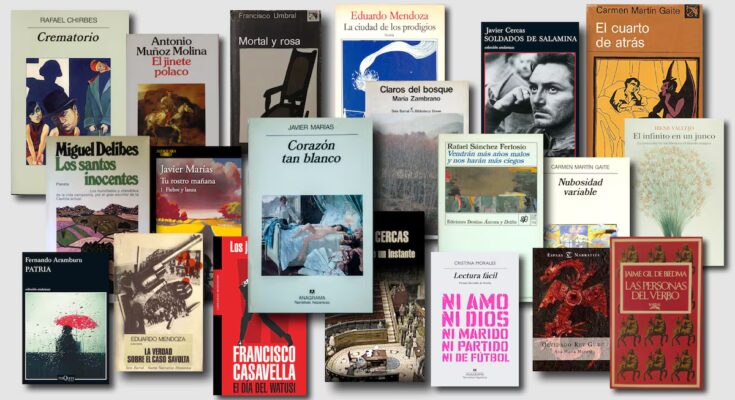

At the end of 1991, Spain was the guest of honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Here are the new names of a novel that marked the distance with the Latin American masters and had short-circuited its link with traditionalism through experimentation and its link with international postmodernism. That eagerness for modernization was registered by the supplement Books from EL PAÍS a few weeks before the birth of Babelia. A ranking of the best books since 1975 was drawn up, “around 60 qualified readers” participated and the 15 most voted were highlighted. Won The truth about the Savolta case (1975), by Eduardo Mendoza, the radiating center of prestige was Juan Benet and not a single book written by a woman stood out and no one was ashamed of it.

Who is in that pantheon? In a certain sense, that list recognized the writers who during the second half of the dictatorship and the Transition already laid with their work the foundations on which the democratic city would be built, to quote an idea that Manuel Vázquez Montalbán was developing in that period.

At the beginning of the nineties that city, destroyed in 1936, was already a reality. Four books were then published that were fundamental for the careers of their authors and, at the same time, for the sentimental formation of a new and large middle class of readers for whom good democratic culture constituted the complicit reference and daily normality. The books were Him knight Polish (1991), by Antonio Muñoz Molina; Heart so white (1992), by Javier Marías; Variable cloud cover (1992), by Carmen Martín Gaite, e More bad years will come and you will make us more blind (1993), by Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio.

We could close the circle and say that at the end of the 1980s Javier Cercas had already sharpened his pencil to write his first new and that the luminous critical conscience of this process of political and cultural normalization – I am obviously referring to Rafael Chirbes – had debuted in 1988 with Mimoun.

What changed with those four books? It is not that literature has been depoliticized nor that the formalist risk has been sacrificed. There will be those who want to understand what happened then as a symptom of the end of history or of the wavering postmodern void. These are interesting interpretations if you think from theory or ideology. And so, in attempting to formally construct meaning, they are partial. What was happening, after decades of anomaly fought even by the best literature, is that finally the subject and subjectivity, the reflection on identity and the relationship with others could occupy the central space typical of literature in contemporary democratic society.

This is understandable, I think, because in 1991 a plethora of lyric corpus that we now consider classics was not on the list: the morality lesson that is The people of the verb (1975), by Jaime Gil de Biedma; the exploration of the epistemological limits of reason forest glades (1977), by María Zambrano; the pain of loss Deadly and pink (1975), by Francisco Umbral, which continues to touch the fibers that define us. And so we understand the canonical centrality that Virginia Woolf’s heir already occupies in Spanish literature: Carmen Martín Gaite has placed five books in the top 50 and her work has 351 points.

In 2022, Spain was again invited to the Frankfurt Fair. From Babelia A new ranking has been drawn up, this time on the best Spanish books of the 21st century. There it was already clear who is considered our best novelist of democracy: Javier Marías. Now Marías has 462 points and Chirbes 311. But in 2022 perhaps it has not been possible to perceive what this survey signals and which speaks of that reader of democracy who debuted with the maturity in the nineties and also of the one who debuted with his around the economic crisis of 2008. The other Spain.

With the advent of the new century, an in-depth review exercise began on the foundations, silences and corrosion of that democratic city. The two main works of Javier Cercas —Soldiers of Salamis (2001) e Anatomy of a moment (2009) – have forced us to reformulate outstanding questions about our relationship with the contemporary past; Homeland (2016), by Fernando Aramburu, held a mirror up to Basque society to understand the human dimension of the worst conflict that the country has suffered in this half century, and Mater Dolorosa (2001), by José Álvarez Junco, revealed how nationalism shaped Spanish identity. At the same time, Chirbes’ dissidence acquired centrality because the watered-down versions of the present lost credibility for the new generations of readers. The same ones who were fascinated by the dissident voice of Cristina Morales in Reading easy (2018), a fiction that opens the front to a new battlefield.