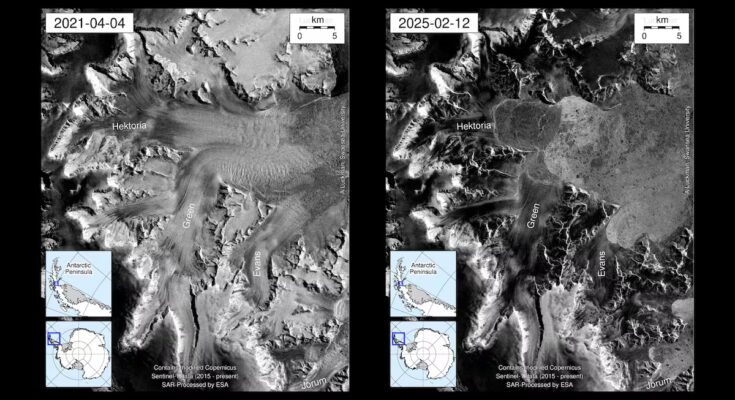

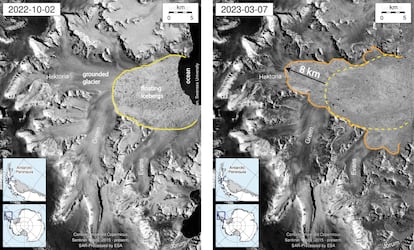

Researchers from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and France have documented a record retreat of the Hektoria Glacier on the Antarctic Peninsula by more than eight kilometers in just two months. The measurement is part of a study published this week on Nature geosciencewhich analyzes this surprising loss of ice on land between November and December 2022, at a rate almost 10 times faster than observed so far.

Land-based glaciers in the polar regions generally retreat no more than a few hundred meters per year, but in the case of Hektoria, scientists calculated, using satellite and aerial images as well as ground-based altimetry data, a loss of about 800 meters per day.

As Etienne Berthier, glaciologist at the Laboratory of Spatial Geophysical Studies and Oceanography of the University of Toulouse (France) and one of the authors of the work, explains, “such strong and rapid retreats are commonly observed on floating ice shelves, when the glacier ends with a tongue of ice on the sea, where the largest icebergs form, but what is so extraordinary here is that it happened with the ice resting on the bedrock and for more than eight kilometers in such a “Just two months for this type of glacier is truly spectacular.”

Unlike what happens with floating ice, when the melting occurs on land and the water goes directly to the sea, it is also relevant because it contributes to the rise of ocean levels. Therefore, understanding how polar glaciers behave and what factors influence their rate of retreat is crucial to accurately predict how much the rise of water on the coasts of continents will increase due to global warming.

According to Berthier, never before has there been a reduction in land ice of the magnitude observed in Hektoria with satellites, airplanes or ground-based scientific observations. However, estimates have been made on the speed of retreat of the polar ice cap that covered Scandinavia 20,000 years ago, based on the morphological traces left by the ice, which indicate that retreat periods of this magnitude, of several hundred meters per day, have occurred in the past.

“This is the only analogy we know with the past of such rapid retreat, but it is important because it shows that in very rapid warming periods, polar mass instabilities can occur with such extraordinary reductions for ice resting on bedrock,” comments the glaciologist from the University of Toulouse.

The researchers conclude that the incredible rate of melting that occurred in this part of the Antarctic Peninsula has to do with the physical peculiarities of the surface on which the Hektoria glacier rests. Specifically because it is a particularly flat terrain near the coast, which causes small variations to bring a large surface of ice into contact with the sea.

However, Berthier explains in detail how this whole process is also linked to the disintegration, in 2002, of the gigantic ice barrier called Larsen B. That phenomenon which occurred more than two decades ago accelerated the melting of the glaciers that were about to give way to this floating platform, since the ice barriers on the sea act like a bottle cap that contains the melt that comes from the land. “After all, the entire evolution of this Antarctic region is linked to global warming,” underlines the glaciologist, who believes that the collapse of Larsen B and the current record of the Hektoria glacier are part of “a chain reaction” caused by rising temperatures.

Among the multiple impacts linked to the melting of the Earth’s frozen masses, the rise in sea levels is the one that affects humanity the most. In this regard, after the warming of the oceans themselves (which increases their volume due to expansion), the other causes of the rising waters on the planet are the melting of mountain glaciers and the melting of the polar ice caps of Greenland and Antarctica. Right now, each party contributes about a third.