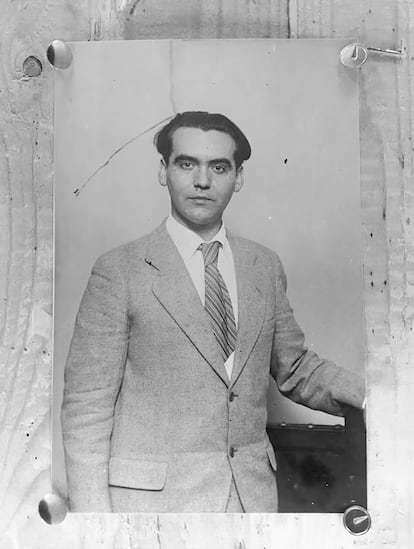

In the summer of 1936, after hearing the news of Federico García Lorca’s execution, the rescue of the poet’s papers, manuscripts, letters, photographs and drawings began. A story to which, in the almost 90 years since his murder, just a month after the military revolt against the government of the Republic and the outbreak of the Civil War, pages continue to be added. Access to the original frames and high-resolution digitization of the documentary on the La Barraca theater company shot by Gonzalo Menéndez-Pidal in 1932 (which is preserved in his private archive in the Segovian city of San Rafael and is available on YouTube) allowed director Manuel Menchón to process the images until he discovered the poet’s face in one of the trucks. Lorca’s face also stood out more clearly in another image in which he appears on stage in the performance of life is a dream in the role of Shadow. Menchón is working on the documentary about Lorca, The broken voicewhose theatrical release is expected in the first half of 2026, and explains in a telephone conversation that he consulted numerous archives in Spain and abroad to prepare his film.

The documentary by Gonzalo Menéndez Pidal on which Menchón worked is one of two known films in which Lorca appears. The other was made in Montevideo in 1934 by Enrique Amorim, who much later was contacted by Isabel, the poet’s younger sister, and prepared a copy for the Lorca family in the late 1950s. Today that recording is found in the archive of the Federico García Lorca Foundation, founded by the family in 1984 and kept in the Student Residence until 2018 when it was transferred to the Federico García Lorca Center in Granada. The exhibition Lorca and the archive. Memory in motion, presented in that same center in 2025 and which will travel in April 2026 to the Student Residence in Madrid, has reconstructed the long and complex history of the documentation relating to the creator, who tragically passed away.

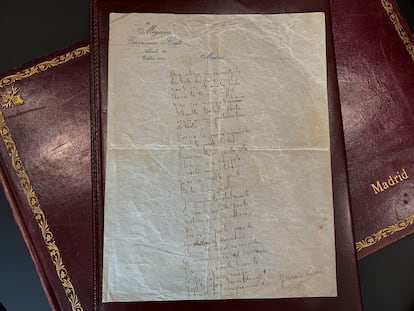

The result of four years of research, the exhibition, curated by Christopher Maurer, Andrew A. Anderson and Melissa D winter, is made up of 460 pieces, many of which are unpublished or little known, after having studied almost 50 personal, family and state archives from Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the United States and Spain. Lorca’s archive consists of “thousands of documents and countless gaps that evoke the absent poet,” Maurer writes in the exhibition publication, and continues: “An envelope, a trunk, a bank box, a room with a double lock, the drawer of a bedside table, a sealed package – objects and spaces associated with the poet’s manuscripts – somehow evoke the empty tomb.”

The story of those papers, drawings, manuscripts, documents and photographs that have been added layer by layer since 1936 is also that of those who preserved them and the different twists and turns through which they emerged. “With the arrival of the exiles in the Seventies and Eighties, abundant unpublished works appeared, then what is found decreases. Many false drawings emerge, yes”, he underlines in the videoconference, and does not exclude that in the future there will be new epistolary or photographic discoveries, and even that there are materials deposited in a safe.

What important materials are still missing? Andrew A. Anderson points out the absence to date of any recording of Lorca’s voice, as well as scores written by him. “There is evidence of his participation in radio programs, but those materials did not appear,” explains the academician. “When Lorca was in Buenos Aires he gave conferences on three stations: Radio Stentor (whose offices were in the Hotel Castelar where he was staying), Radio Prieto and Radio Splendid. And when he returned to Madrid, he also gave some conferences on Radio Unión.” Some of the texts read on those stations were found, not the recordings.

Among the lost materials, Anderson and Maurer, in relation to the correspondence, highlight the letters with Salvador Dalí. Links are also missing in the textual chain of some works, such as the manuscript version of Bernarda Alba’s house and the more advanced and revised versions The audience (the known draft was purchased from the National Library by Rafael Martínez Nadal in 1997), or directly lost texts such as The girl who waters the basil and the prince who asks for itopera performed as a puppet in 1923 in Granada by Lorca, accompanied by the music of Manuel de Falla and the scenes and puppets by Hermenegildo Lanz. The original of one of Lorca’s drawings, bust of manincluded in the edition of Poet in New York we cannot even find the one made by José Bergamín in the Séneca editions, nor the original Five years pass like thiss, which Martínez Nadal published in facsimile in 1979. Lorca’s letters to the critic Juan Ramírez de Lucas, with whom he had an intimate relationship shortly before his death, have not yet been shown publicly.

“One letter leads to another and it is very likely that they will continue to appear,” explain Maurer and Anderson, who are working on a new edition of the poet’s letters. Alicia Gómez Navarro, director of the Student House, an institution that preserves a digital copy of the archive of the Federico García Lorca Foundation, underlines this link between archives and letters: “In our documentation center a cross-dialogue is established with other archives, such as those of Rosa García Ascot, Luis Cernuda, Gustavo Durán, Juan Gutiérrez Gili, Benjamín Jarnés, José Moreno Villa or León Sánchez Cuesta, among others.

“The archives that may contain Lorca’s objects are all over the world, and this is a natural effect of war and exile,” explains Melissa D winter, who is working on a map that allows us to trace the paths of these materials. “It’s the detective’s job, because every archive has its own story, its own path of exile and friendship. That things keep coming out shouldn’t be surprising, it’s the result of the vicissitudes of those lives. What you find is interesting, but also the story of how he ended up there. Lorca is somehow always under construction because it changes the way his work and his story are received.” Perhaps this is why Laura García Lorca, president of the Federico García Lorca Foundation and responsible for programming the center of Granada, underlines the constant dialogue that contemporary artists have with the poet’s legacy and which make his story a “living memory”.