The photograph captures a decisive moment: a monumental statue of the philosopher Friedrich Engels hangs in the air. In the background, apartment blocks coexist with the St. Mary’s Church tower and the television tower in East Berlin’s historic Mitte district, underlining the contrast between past and present. Its author is the German photographer Sibylle Bergemann (1941-2010), one of the great references of German photography of the last decades of the 20th century. Seen today, the image invites us to think that we are faced with yet another document of the decline of an idol; read the scene as a retreat, the consequence of a historical turning point. However, the image was taken during the installation process of the Marx-Engels Forum, dedicated to the two central figures of official history. A detail that dismantles our first certainties and reveals how history – and our gaze – can reverse the meaning of the same image.

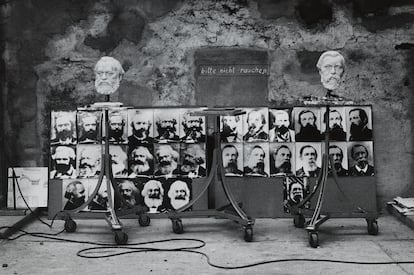

The image is part of the exhibition Sibilla Bergemann. The Monumentat the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. Curated by Sonia Voss, the exhibition is based on a series of 12 photographs collected by the author under the title Das Denkmal (The Monument), coming from the 400 reels shot over 11 years while documenting the construction of the memorial dedicated to the two theorists of Marxism. Conceived around two walls, the exhibition contrasts the emblematic series with what the author discarded from her archive, with the aim of understanding the conditions in which the work was created and drawing contrasts that allow us to glimpse where the artist’s gaze was directed.

Bergemann was 34 years old when, in 1975, she undertook this photographic project, which reflects the interaction between space, memory and ideology, developing the sober and direct style that would make her one of the most unique voices of German photography of her time. He grew up on the outskirts of Berlin as Allied bombing devastated the capital. He began his photographic career in 1965, working for the well-known magazine Das Magasin. His melancholic and elegant style is refined as he develops his collaborations linked to the world of fashion and culture. He documented the transformations that occurred in the city and its surroundings, both in the years before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, challenging the dominant propaganda style of the time, as shown in the series in question. “The Monument “It offers a key to understanding the photographer’s work despite being an exception”, underlines the curator.

The idea of dedicating a monument to the authors of Communist poster It emerged in the early 1950s, in the turbulent atmosphere that accompanied the creation of the German Democratic Republic. However, this did not begin to materialize until 1973, when the task fell to sculptor Ludwig Engelhardt, who in turn decided to surround himself with other artists. The sculptors Werner Stötzer and Margret Middell were commissioned to create two reliefs that represented the subjugation and liberation of the people, while the photographer Arno Fischer and the director Peter Voigt worked on eight steles with engraved photographs that showed the same type of dialectic: a working class oppressed by the capitalist yoke and emancipated through its own struggle.

The photographer began working on the project informally until she received an official assignment in 1977. “Then she was appreciated more for the uniqueness of her gaze than for her compliance with the codes of the report,” notes the commissioner. “Her closeness to Fischer, who became her partner, as well as to Voigt and Engelhardt, was decisive in the choice of the assignment. In this way, the photographer had the necessary margins of freedom to be able not only to bear witness to her subject, but also to fix it permanently in our imagination. “Just as after the Second World War, due to the barbarism experienced, people had hope and trust in the new system, at that time many citizens were disappointed by the ideas proclaimed by their rulers”, warns the curator “There was respect for the philosophers, but most artists had already distanced themselves from the official discourse.”

Bergemann’s photography is austere and direct, as documentary as it is subtle. He always manages to grasp the potential of every situation; His gaze moves between the lines, combining rigorous and analytical analysis with a sensitivity capable of deciphering what others overlook. By photographing each phase of the project under a gaze capable of combining documentary precision with the ambiguity inherent in each shot, the artist managed to give the series a tone that is as ironic as it is close to the unreal. This ambivalence was fundamental to the fame of the series, especially after the fall of the Wall in 1989, when the images acquired completely different readings. The deconstruction of the heroic figures and the latent irony in the photographs thus prove surprisingly prescient, anticipating changes that few could have foreseen.

“By comparing all the photographs that make up the archive of The Monument With the images selected by the photographer, she draws attention to how she carefully erases the human presence,” warns the curator. “No doubt she intended to reject the official pathos surrounding the worker. But it also seems to break with the tradition of humanist photography, particularly charged with meaning in the GDR, which is quite bold.”

However, “Bergemann never intended to be critical,” says Voss. He said he simply photographed what was before his eyes. “Those who knew her highlighted her laconic humor, as well as her discretion,” underlines the curator in the publication accompanying the exhibition of the same title. “Diametrically opposed to the precepts of Robert Capa (“If your photos are not good, it is because you are not close enough”), Bergemann’s subjectivity is supported by a certain detachment. His visual ethic is in this sense closer to the theatrical principle of distancing than to the imperatives of the photojournalism of his time.” A concept developed by Bertolt Brecht which seeks to ensure that the work is contemplated with critical distance rather than the audience being totally emotionally immersed.

In 1990 the publication of a book that brings together Bergemann’s photographs with Heiner Müller’s poems was consolidated The Monument as an artistic reference in a singular moment in German history. Photography, far from being limited to mere representation, becomes a means capable of illuminating reality, interpreting it and taking a position; In this sense, Bergemann’s images seem to whisper the transience of political ideas, reminding us that what seems immutable can vanish under the weight of time and history.

Sibylle Bergemann.The monument. Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation. Paris. Until January 11th.

Sibylle Bergermann.The monument. Kerber. 160 pages. 45 euros.