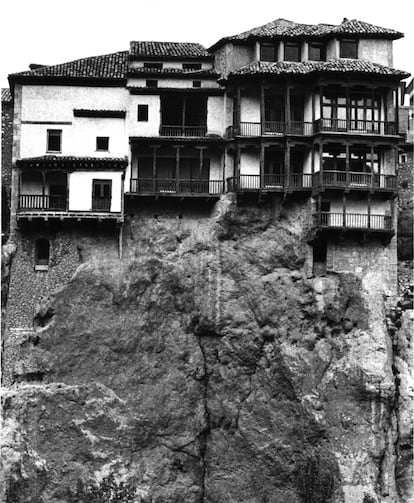

For Cuenca there is a before and after the arrival of the Filipino patron and artist Fernando Zóbel and the group of creators with whom he created the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in 1966 in one of the beautiful Hanging Houses overlooking the gorge of the Huécar river. In that Spain of the dictatorship there were still few museums and none dedicated to contemporary art. The creator accomplished the miracle with his generosity and with the help of his great friend Gustavo Torner, who recently passed away at the age of 100. And of other great creators such as Gerardo Rueda, Manolo Millares, Antonio Saura, Eusebio Sempere, José Guerrero, José María Yturralde and Jordi Teixidor, among others.

Celina Quintas, director of the museum (since 1981 it has been owned by the Juan March Foundation) recalls that this was one of the first directed by artists in Spain. Zóbel’s project supported an entire generation of painters and sculptors, paved the way for subsequent ones and led to the birth of a new audience. For example, its rooms, which welcome more than 80,000 visitors a year, host one of the most representative groups of Spanish abstract art of the second half of the 20th century.

Written documentation of the birth and evolution of the museum is preserved in the form of catalogs of each of the exhibitions and a photographic collection of the highest level is preserved. But the most innovative thing about the museum is the audiovisual archive that David Plaza, head of the March Foundation’s educational program, launched in 2021, in the middle of the pandemic. A project still in progress and the results of which were seen and heard in two episodes. The third has just been ready to be seen by the public.

Plaza explains that his idea was to create an oral history archive recorded on video with the testimonies of the people who lived around the museum and the historic center of Cuenca from the 1960s until the death of Fernando Zóbel in 1984. The complete archive, intended for research, will be available in the future to those who request it. “At the same time”, he adds, “I am curating audiovisual chapters with informative intentions, which have been exhibited in Room Z of the museum and in international institutions such as the Ayala Museum (Philippines) and the National Gallery of Singapore, in the latter case within the exhibition Fernando Zóbel: Order is essential.”

All those interviewed for the audiovisuals are residents of the historic center of Cuenca which coincided with Zóbel and witnessed the transformation of the city. In the first two episodes you can also find testimonies from former scholarship recipients, regular travelers or artists devoted to the museum such as Antonio López, Elvireta Escobio or Rafael Canogar. Everyone is invited to tell, briefly, what they remember about the creation of the museum almost sixty years ago, the impact on their lives, but also on the neighborhood in which they live and the city that surrounds it and how they have changed.

“The protagonists, many of them experts on the museum and the city”, explains David Plaza, “tell and tell the world about their relationship with Fernando Zóbel and how he influenced their lives”. The result is an archive of memory and a chronicle of memories, an authentic “oral history”, in the expression used by Joseph Gould, in 1972, to vindicate his work as a historian of Greenwich Village (New York), when he wandered through streets, squares and houses writing stories about the people of that New York neighborhood.

The testimonies of both complete the puzzle of the personality of one of the most appreciated artists and patrons of the 20th century and most loved in Cuenca. As proof of that love, Celina Quintas remembers the farewell funeral that was dedicated to him on 6 June 1984, when thousands of people crowded the two uphill kilometers that separate the cathedral from the small cemetery of San Isidro where he was buried.

Global impact

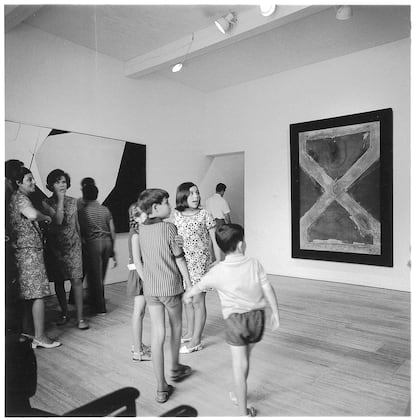

The global impact began almost from the inauguration of the space. The magazine time was in preparations for the inauguration and published an extensive report entitled A new view from the cliff (A new view from the ravine), published on July 29, 1966. The visit of Alfred Barr, first director of the MoMA in New York, contributed to the international prestige of Cuenca, calling it “the most beautiful small museum in the world”. It was 1967 and the influential historian was the guest of honor at the lunch that the artists dedicated to him at Eusebio Sempere’s house.

But there is an equally important sign and it concerns the impact that the museum has had on the life of the city. Owner of an open and very curious character, Zóbel was a close and affectionate neighbor to everyone. It was common to see him walking around the city with his camera around his neck, photographing children and adults and listening to their personal stories. These images of the common people of Cuenca in the 1960s and 1970s provide the museum with an invaluable photographic heritage of the city’s history.

Zóbel was tasked with finding the perfect home to display his collection of abstract art, the seed of the museum. Subsequently, the artist sought accommodation for his colleagues in the Hanging Houses, all of which had previously been rehabilitated by the city council. Antonio Saura arrived there, settling in a laboratory-house that alternated with the one he owned in Paris. Gustavo Torner of Cuenca had his own house; After all, he was largely responsible for Cuenca being the city chosen for the museum, after Toledo had been tested as a possibility. The two artists met at the Venice Biennale in 1962 and on their return they toured the streets. The Filipino was shocked by the dazzling landscape surrounding the architectural complex. The support of the municipal team did the rest.

To adapt the museum and the artists’ houses, the foreigner Zóbel turned to painters, carpenters, cabinetmakers, electricians or stonemasons who lived in the area. With him, existing professions prospered and others linked to the museum’s activity were born: framers, assemblers and entrepreneurs.

In the shadow of the Museum of Abstract Art, the Faculty of Fine Arts of Cuenca was created and over time other cultural institutions arose such as the Antonio Pérez Foundation, the Espacio Torner, Casa Zavala and the art center dedicated to the Roberto Polo collection.