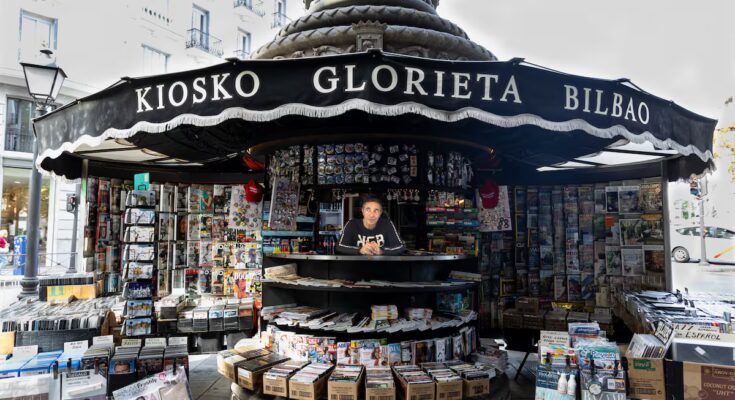

Located in the Glorieta de Bilbao, in front of the emblematic Café Comercial, Rafael Martín’s kiosk stands like a small circular island lined with newspapers, magazines, films, vinyl records for the most music lovers and even table football cards. At 58, Martín represents the third generation of a family linked to the press for almost a century and his is one of just 300 kiosks still open in the capital. “Before the sale was on the street, with a stool, a table and sometimes not even that, but with a pile of newspapers on the floor. It was advertised at the entrance to the subway”, he recalls from the place that his family has managed since 1979 and where he started working at the age of 15. After a life behind the counter, he wonders what will happen on September 15, 2029, a date still far away but marked in red on the calendar of Madrid newsstands. It will be then that over 200 municipal press concessions will expire.

Will Madrid be reborn without newspapers on September 16, 2029?, asks the Association of Professional Press Sellers of Madrid (AVPPM) before underlining the uncertainty of not knowing whether the permits will be abolished or renewed, and based on what criteria. An uncertain future that especially affects a sector whose sales have decreased drastically in recent years and in which generational turnover presents itself as a difficult challenge to face. Martín, who serves on the AVPPM board of directors, has seen the decline in business firsthand. “Now less than 10% of what was sold before is sold,” he says to underline three key moments: the arrival of the Internet, the 2008 crisis and the pandemic.

“With this situation it is difficult for young people to encourage themselves to continue, even more so if they don’t know what will happen starting from 2029. Furthermore, those who are close to retirement (about 70 people according to the association) discover that no one will pay a transfer for something that can disappear in less than four years,” explains Martín to ask for clarity from the Municipality. A need that adds to others such as that of “a more open and flexible vision” that allows diversifying the product offering in the kiosks. The goal: to alleviate declining demand for newspapers and magazines and reach a younger audience.

Municipal sources contacted by this newspaper underline their commitment to collaborating and coordinating with newsagents to respond to their requests. As this plays out, vendors seek to adapt to the needs of their neighborhoods and expand their offerings to survive. In the case of Rafael Martín, the boxes full of DVDs in which customers search for titles with which to expand their collection denote a commitment to the classic. “Films are my main source of income right now, above print. Video stores have closed and the big specialty stores almost don’t carry them anymore,” explains Martín about a catalog to which he recently added vinyl and which he defends against “gentrification and the invasion of franchises” in the neighborhoods.

“The kiosks are not just press, but we are the essence of small businesses and I think it is something that we must defend and protect. They ask us for directions, they ask us for change, we know the whole neighborhood and the whole neighborhood knows us… We are a public service. A grain of sand in that desert of increasingly impersonal businesses”, Martín forgets.

This resistance is well embodied by Mariano Mayo from the kiosk of the Glorieta de Ruiz Giménez, in Chamberí. His story as a salesman began at the age of eight, delivering newspapers from house to house. Today, at 72 years old, he continues to set the alarm for five in the morning and, an hour and a half later, to raise the shutters of the business inherited from his grandmother. “Before you didn’t stop. The newspapers arrived first thing in the morning and you didn’t even have time to unpack the magazines. Now you don’t sell anything in the morning, but I continue to open the same way”, recalls Mayo.

It has just changed its offer: press, magazines and collectibles, above all, although it recognizes that it has more and more products. “I still live on paper. Then you can sell something else, a bag, a wallet, but the main thing is still newspapers and magazines.” While it remains its main source of income, Mayo is resigned to the situation in the sector and sees the pandemic as a turning point.

“In 2008 we noticed the crisis, but then it recovered. Now we won’t do it. Teleworking hurt us a lot because before people went to have breakfast at the bar under the office, went out to buy the newspaper… Now they work from home and don’t set foot on the street”, Mayo reflects on the difficulties of his job.

However, the experienced newsagent predicts that this job will continue to exist in one form or another and, while he awaits the arrival of September 15, 2029 without knowing whether his business will have to turn off the lights or will last over time, he is clear that he does not want his children to take over: “It is a very sacrificial job and it bears less and less fruit. I don’t want them to work here and neither do they.”

A necessary relief

The one who chose to follow in his father’s footsteps is Ángel Martínez. At 37, this Environmental Sciences graduate has one in front of the kiosk on Rodríguez Marín street. “I have been coming since I was a child and have worked here at different times. A year ago my father retired after 42 years in this kiosk”, explains the new owner.

With a smile on his face, Martínez is committed to keeping open a factory that is already part of the urban landscape. Some come for the newspaper, others for the tobacco and still others come in search of the latest collectible warplane. “We provide a service that goes beyond what it seems. There are elderly people who come every day and who you spend 20 minutes talking to. It’s not just selling a newspaper, it’s being part of those neighbors’ routine and, in a way, giving them life,” he says.

This is the part that motivates him most about a job that closes for only three days a year (Christmas, New Year and Holy Saturday) and which tries to reinvent itself by adding services such as the collection and return of parcels, but without losing its essence. “I would like to be able to live by just selling newspapers and magazines, but you have to do the math. The margin left by the parcels is ridiculous, around 70 euros a month, and they involve a lot of work”, he explains, speaking of a service which, at times, translates into the sale of some of the products he displays in his small business.

Martínez is aware that he embodies the exception: a young newsagent. He admits that most of his colleagues “are over 50” and although he understands that the younger generation believes his business has no future, he does not share this position. “Young people think that this almost doesn’t exist anymore, that it won’t work, but that’s not true. If you organize yourself and know how to adapt to the neighborhood you’re in, you can earn a living”, he concludes from behind the counter. A life gamble that has just begun and which he hopes to maintain beyond 2029.