Alongside the legions, the miliary marked the power of the Roman Empire. Posted every a thousand steps or Roman mile (1,478.5 meters), these cylindrical or rectangular stone markers dotted Roman roads, just as mileposts do on highways today.

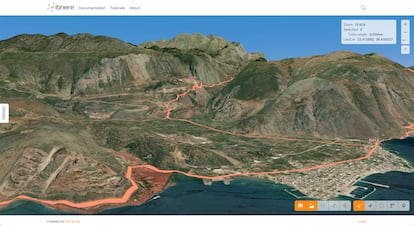

A large group of researchers turned to the latest technologies to delve into historical and archaeological documents in order to reconstruct the 2,000-year-old road map. What they found was that it was much larger, almost double than previously believed. They also discovered that very little of its original layout remains. The results of their work, published in Scientific datathey were compiled and made public on Itiner-e, the digital atlas of the streets that started or ended in Rome.

“When you walk along a path carved by time and travelers, people still say: ‘this was a Roman road,’ but the Romans built them last,” says Pau de Soto, of the Archaeological Research Group of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and lead author of this impressive study. “Another misconception that we wanted to dispel is that they were paved with stone slabs, like the Via Appia. In fact, they were built in successive layers of gravel, one finer than the other, with the upper layer made up of compacted fine gravel. That was the best thing for the horses, which at the time did not yet wear horseshoes”, adds the archaeologist.

Like modern roads, they were raised above the surrounding terrain and had a gentle slope to drain water. “The first modern roads were built following the Roman model,” notes the archaeologist.

Pau de Soto and around twenty researchers used modern GIS (Geographic Information System) techniques to bring to light the layout of Roman roads. “GIS is the foundation of modern archaeological research,” says the UAB researcher.

They combined historical texts such as the Antoninian itinerary and the Tabula Peutingeriana — the closest thing to a road map of antiquity — with studies of archaeological sites and books on Roman history. “But we also used topographic maps from the 19th and 20th centuries, post-war aerial photographs taken by the Americans, and satellite images; GIS allows you to combine data from all these sources and project it onto the ground,” adds De Soto.

The result of combining so many sources is that, around the year 150 AD – when the Roman Empire was at the height of its expansion, covering around four million square kilometers (1.5 million square miles) – the network included 299,171 kilometers (around 186,000 miles) of roads. This figure adds more than 100,000 kilometers (62,000 miles) to the 188,555 kilometers (117,000 miles) counted in previous studies and is equivalent to circling the planet seven times. In Spain alone, the length of Roman roads exceeded 40,000 kilometers, double what was estimated. At that time there was no radial distribution centered on Madrid, as in modern highways, but several main roads branched off from cities such as Augusta Emerita (Mérida), capital of Roman Lusitania.

The authors of the new study estimate that one-third of the roads connected major urban centers, while the remaining two-thirds were secondary routes connecting settlements on a local or regional scale. However, they found that certainty only exists for 2.7% of total mileage. “This is what still survives or has been excavated in archaeological work,” De Soto explains.

For the vast majority of Roman roads – almost 90% – there are only traces that suggest where they must have been: “In landscape archeology we call them fossilized axes, which could be a Roman bridge, remains of a road on the outskirts of a city, or the discovery of a miliarium,” says De Soto.

Everything indicates that a road had to connect those elements. What GIS does is model the most plausible route between them, taking into account the topography of the terrain, such as a mountain pass or a river crossing. Another 7% of the map total is purely hypothetical: if two Roman cities are located close to each other and both have remnants of streets at their exits, it is reasonable to assume that they were once connected by a road.

“Roman roads – and the transportation network as a whole – were absolutely crucial to the maintenance of the Roman Empire,” says historian Adam Pažout of Aarhus University in Denmark, a co-author of the study. “The Romans devised an intricate transportation system of inns, roadside stations, and meeting points for couriers and public officials traveling through Italy and the provinces,” he recalls.

For Pažout, “the streets formed a structure that allowed Roman power to be projected – through the army, law or administration – and that held the Empire together.”

According to the authors, their work will allow a better understanding of the history of Rome. Millions of people traveled along these roads, new ideas and beliefs spread and Roman legions and merchants moved between the most remote corners of the three continents that made up the Empire. But these routes – the immense scale of which is only now being revealed – also helped spread diseases and plagues such as Antoninus’ smallpox or measles epidemic and Justinian’s bubonic plague, both of which weakened the Empire. They may also have served as routes for later barbarian invasions.

What remains of Roman roads, although not many thousands in physical length, are still part of the fabric of Europe. As archaeologist Pau de Soto reminds us: “The European urban fabric is a legacy of Rome. Most European cities already existed in Roman times and were already connected to each other.”

Sign up to our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition