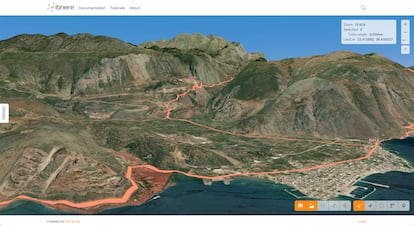

Together with the legions, the milestones marked the power of the Roman Empire. Placed every thousand passus or Roman mile (1,478.5 meters), these cylindrical or parallelepiped signs marked Roman roads, as kilometer points do with highways today. A large group of researchers used the latest technology to dig into historical and archaeological documents to reconstruct the 2,000-year-old road map. What they found was that it was much larger, almost double, than previously believed. But they also found that almost nothing remains of its original layout. The results of his work, published in Scientific datathey collected them and opened them to the public on the Itiner-e website, a digital atlas of the routes that were born or died in Rome.

“When you walk down a path that has been heavily carved out by the passage of time and people, you still say that ‘it was a Roman road,’ but the Romans made it last,” says Pau de Soto, of the Archaeological Research Group of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and first author of this impressive work. “Another belief to dispel is that they made them asphalted, like the Appian Way. In reality they made them with layers of increasingly fine gravel, with the tread layer made up of compacted fine gravel. It was the best for the passage of horses, who at that time did not yet wear shoes”, adds the archaeologist. Like current roads, they were raised above the surrounding terrain and with a slight slope to allow water to evacuate. “The first modern roads were built after the Romans,” recalls the archaeologist.

Pau de Soto and around twenty researchers used modern GIS (Geographic Information System) techniques to bring to light the layout of Roman roads. “GIS is the basis of modern archaeological research,” says the UAB researcher. They combined historical texts such as Antonine itinerary wave Tabula Peutingerianathe closest thing to a road map of antiquity, with studies on archaeological sites, or Roman history books. “But also with topographic maps from the 19th and 20th centuries, the photographs that Americans took of European soils after the war or satellite images; GIS allows you to combine information from all these sources and capture it on the ground,” adds de Soto.

The result of the sum of many sources is that, around the year 150 of this era, the Roman Empire – then at its moment of maximum expansion, covering around four million square kilometers of territory – had 299,171 kilometers of roads. The figure represents the addition of more than one hundred thousand to the 188,555 km counted in previous works and is equivalent to going around the planet seven times. In Spain alone, the length of Roman roads exceeded 40,000 km, doubling that assumed to date. At that time there was no radial distribution centered in Madrid that characterizes modern roads, but some of the main roads started from cities such as Augusta Emerita (Mérida), capital of Roman Lusitania.

The authors of the new study estimate that a third connect major urban centers; and the remaining two-thirds would be secondary, connecting populations on a local or regional scale. However, they verified that there is only 2.7% mileage certainty. “It is what is still preserved or what has been excavated in archaeological works,” specifies de Soto, who explains that, of the vast majority of Roman roads – almost 90% – there are only indications that they were supposed to be there: “In the archeology of the passage we call them fossilized axes, and they can be a Roman bridge, the remains of a road at the exit of the city or the discovery of a milestone.” Everything indicates that a road must have united all these elements. What a GIS does is imagine the most reasonable route taking into account the topography of the terrain, such as crossing a mountain or crossing a river. Another 7% of the total road map It would only be hypothetical: if there are two Roman cities close together with remains of a road at the exit, one would expect them to be connected by one.

“Roads – and the transport network as a whole – were absolutely crucial to the maintenance of the Roman Empire,” says historian from Aarhus University (Denmark) and co-author of the study, Adam Pažout. “The Romans devised an intricate transportation system of inns, way stations, and meeting points for messengers and public officials traveling through Italy and the provinces,” he recalls. For Pažout, “the streets constituted a scaffolding that allowed Roman power to be projected, both through the army and through law and administration, and that held the Empire together.”

According to the authors, their work will allow a better knowledge of the history of Rome. Millions of people moved along the roads, new ideas and beliefs spread; and through them the Roman legions or trade between the different parts of the three continents that formed the Roman territory also advanced. But these routes, the enormous capillarity of which is discovered today, also facilitated the transmission of diseases and plagues such as the Antonine plague of smallpox or measles or the Justinianic plague of bubonic plague, which weakened the Empire. They may also have been the entry routes for subsequent barbarian invasions.

What remains of the Roman roads, even if physically they are not many kilometres, is part of the picture of Europe. The archaeologist de Soto reminds us: “The European urban fabric is a legacy of Rome. Most European cities already existed in Roman times and were already connected to each other”.