“But this year, without making a fuss, even though I still delayed my graduation by one session (but I had almost finished my exams), they still gave me a new MG, milky white, very tasty. It’s true: my father has more than a billion and there are only a few of us at home. A bite of bread cannot be lost.” Imagine when, in 1963, the first version of Alberto Arbasino’s Fratelli d’Italia was published by Feltrinelli (who is now republishing it), by a young thirty-year-old writer in politically Christian Democratic and culturally communist Italy.

In 1963, when Gruppo 63 was also founded, a large group of avant-garde artists with a great desire to deconstruct novels within novels without knowing how to write them, and you get a thirty-year-old man who wrote what I define as the first and only truly postmodern masterpiece novel, a novel about novels, a novel about cultural discourse, a very sharp and witty elephant novel and without mincing words, the language of the author who was Gadda’s nephew several others would exist. The elephant, as the protagonist himself was called, was then an elephant in the Italian cultural space, an elephant also in the zombie circle of the Strega Prize (never winning one, if not one for lifetime achievements, in the end, to put it in the style of the French Arbasini, thank you, Madame).

Someone will say: but what should I do, read the first by Feltrinelli, or read the one published by Einaudi in 1976, of 659 pages, or read the expanded one by Adelphi, in 1993, of 1371 pages, which one? Had Arbasino lived two hundred years, the Elephant’s work would have continued to flourish, for it was an endless work and only he was able, including friendly and influential intellectuals, to dismantle everyone’s clichés, with many offended, starting with Bassani, who accused him of an intolerable mixture of non-fiction and narrative, and (we read in the material collected in a substantial and timely final essay by Giovanni Agosti, full of events of the time), the Elephant answered: “Now, I always do, and after reading Proust and Musil even more so. Who of today’s Musil and Gide still prefers Gidi’s récit, all clean and precise?”. What is also intolerable are sad moments that become funny and funny moments that become sad. “According to Bassani, in my book you die laughing in the dramatic moments and drown in sorrow in the comic passages. But the best of today’s culture, from Gadda to Brecht, is a mixture of the grotesque and tragedy.”

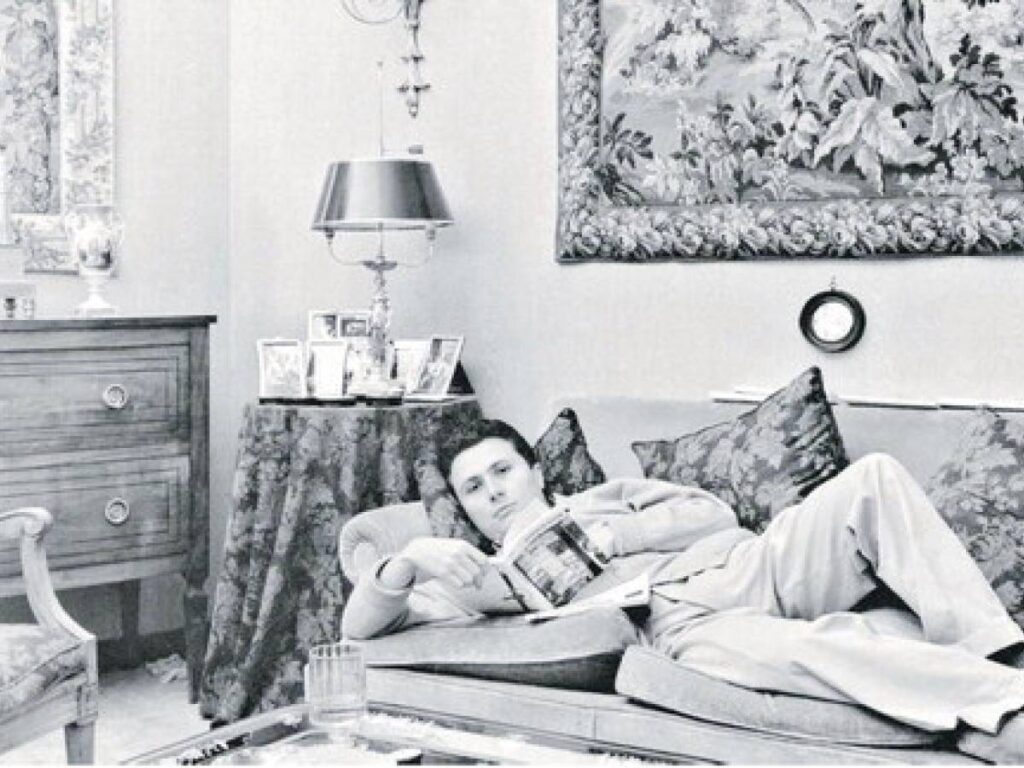

Arbasino was culturally ahead, too ahead, always ahead of everyone, so much so that he is still ahead today, they believe récit gidiano is a French recipe. Always respectful of the right but also viewed with suspicion by certain hegemonies, such as when his friend Pasolini called him a fascist (he viewed with suspicion the 1968 student demonstrations), and said that there was no one more liberal than him, arrogant and liberal, and ça va sans dire, anti-communist, anti-fascist, non-conformist in a suit and tie. In that Fratelli d’Italia he had no problem calmly depicting his homosexuality and the hunt for aviators, there is no San Sebastiano attitude, just look who he is dealing with, the giants, and who they are facing today, among themselves, between left-wing culture and right-wing culture. Brother Italy, the Italy he represents in this unique masterpiece in the world as a very provincial Italy, but compared with him, the whole world is provincial.

Ah, finally, while I was at it, while I was at it, a little personal anecdote: from the late nineties and the following decade, he was among those who had my support as a writer, and there were dozens of postcards from him thanking him for the review, also writing to me that such and such a book ending was not actually his, it was a hidden quote, and while you felt guilty for not understanding it, he added, “I just don’t remember who else darling Max”. Is that kindness? I don’t know.

Because there is a paradox: despite correspondence and telephone reports, I have never met him, I am already a misanthrope, I almost never go far from home, a maximum of fifty meters to the bar. Except one day, it was spring 2018, while enjoying a rum aperitif with Laura Cervellione (now a Rai journalist), he said: “Why don’t we go and visit Arbasino? After all these years, it’s only natural that you see him”. “You said okay” Ethanol answered for me. “But with bare hands?” “And with what?”. Laura saw a flower shop, we bought a pot of begonia, and after half an hour we arrived there, at Arbasino’s house. The Filipino opened the door for us, Alberto arrived in his nightgown, he slowly advanced towards us, but his sight was lost, his mind was already affected by his illness. He no longer knows who I am, but my books are in the library. I took one: “This is me, Alberto, I’m Max.” The last and only image I have of him in person is seeing him back in the darkness of the corridor, heading towards the bedroom, holding a pot of begonias, continuing to say “Thank you, thank you, thank you”.

Thanks to you, Elephant, and if you saw today how many ants stir up in culture, only you never considered the ants, too small to see, and crushed them without realizing it, all it would take is a very large novel.