Today, Earth is the only place in the cosmos where we know for sure that life exists. This absence of confirmed data on other worlds prevents statistics in the classical sense. However, we can make estimates based on our current knowledge of the universe.

It is important to distinguish between the existence of life – which could be microbial and simple – and the emergence of civilizations, understood as forms of life that have developed complex social, cultural and technological structures. Although we like to imagine aliens as intelligent beings, science indicates that if life exists on other planets, it is most likely microscopic. We must not forget that, for much of Earth’s history, life has been dominated by microorganisms, which suggests that biological complexity may take a long time to appear.

The first serious attempt to quantify our expectations of extraterrestrial life was made by astronomer Frank Drake in 1961, with his famous equation. This formula estimates the number of civilizations in our galaxy that can communicate with us, considering factors such as the star formation rate of planetary systems, the fraction of those planets that might be habitable, and the likelihood that life emerged on one of them and evolved to develop intelligence and technology. Finally, a term that we must not disdain is included in the equation: the duration that a civilization with these characteristics could have.

Although the equation was formulated by Drake, it was Carl Sagan who popularized it, turning it into a cultural symbol through his series Cosmos. The values of its variables are uncertain. Using conservative estimates, Drake calculated that there may be a few dozen civilizations in the Milky Way. With more optimistic values, the number could reach billions. If this were true we would have to agree with what the physicist Enrico Fermi claims, who asked himself: “Where is everyone?”, a paradox that remains unanswered.

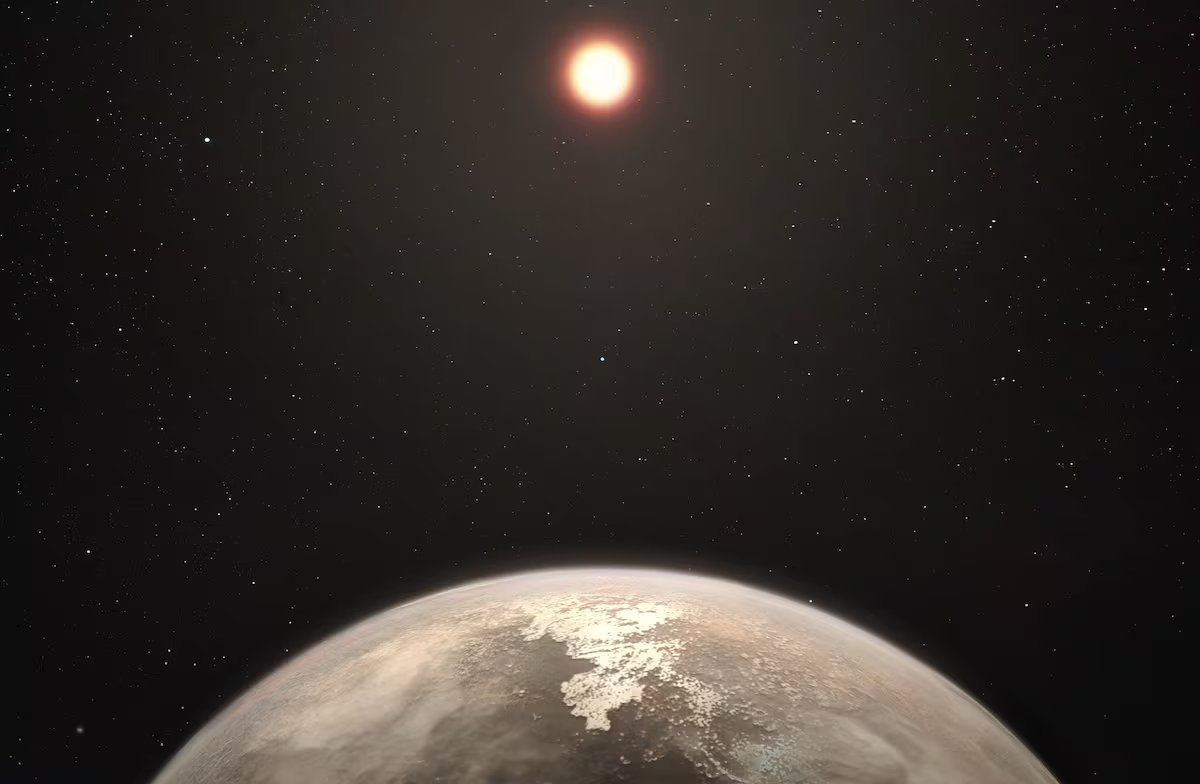

Today we know that the number of planets in the universe is immense, on the order of trillions. Many of them may be in their star’s habitable zone, where liquid water can exist on the surface. Furthermore, recent discoveries have expanded this concept: microbial life has been found on Earth several kilometers deep, suggesting that the planetary subsurface could also harbor life. Even in our solar system there are moons, such as Europa or Enceladus, which hide underground oceans under a thick layer of ice, heated by the gravitational energy of their planets.

All this leads us to think that the potential places for life are numerous. But how likely is it that life will emerge under the right conditions? Although we don’t know the date for sure, life appeared on Earth very early, probably around 3.8 billion years ago. This, on a planet that formed 4.6 billion years ago, and initially suffered two violent waves of meteor bombardment, seems like a record; and makes us think that the road to life might not be so difficult.

Once life emerges, biological evolution facilitates its adaptation to different environments, giving it great resilience. Proof of this are the Extremophiles, organisms capable of living in extreme conditions of temperature, acidity or radiation. We still do not know the physical-chemical limits of life, but what appears clear is that it does not lack the resources to expand and persist.

Thanks to evolution, living beings also increase in complexity. This is how multicellular organisms, plants, animals and, within them, the species which for a long time was considered the pinnacle of evolution, appeared on Earth; that is, the human being. But today we know that our branch on the tree of life is just another, and perhaps it hasn’t even appeared. We also know that intelligence is not the ultimate goal of evolution, but rather one more possibility. Therefore, the existence of technological civilizations is not a guaranteed outcome after the appearance of life on a planet.

It remains to be considered how long an intelligent civilization can last. In our case, in just a few decades we have altered the climate, polluted the oceans, weakened the ozone layer and caused numerous extinctions. Furthermore, we have developed weapons capable of destroying ourselves. Perhaps, in an attempt to improve their quality of life, any intelligent species will end up making their planet uninhabitable.

In short, the question remains open. The combination of astronomical, biological and ecological data brings us ever closer to an answer, even if we cannot yet speak of statistics. And perhaps the most valuable thing about this research is not just discovering whether we are alone, but reflecting on our own civilization: its fragility, its potential, and its place in the universe.

Ester Lázaro is a scientific researcher at the Astrobiology Center (CSIC-INTA), where she heads the group of Experimental Studies on Evolution with Viruses and Microorganisms.

Coordination and writing:Vittoria Toro.

Question sent via email fromJavier Garcia Pedraz.

Scientists respond is a weekly scientific consultation, sponsored by the program L’Oréal-UNESCO ‘For women in science’ and for Bristol Myers Squibbwhich answers readers’ questions about science and technology. They are scientists and technologists, partners of AMIT(Association of Women Researchers and Technologists), those who answer these questions. Send your questions to arespondemos@gmail.comor via X #werespond.