Kenia Carvajal’s voice cracks on the other end of the phone. It’s November 13th. 33 years have passed since four neo-Nazis murdered his mother, Lucrecia Pérez, because she was an immigrant, Dominican and black. And, moreover, he has just learned that José Luis Martínez-Almeida’s PP refuses to support an institutional declaration that honors them on the occasion of the anniversary; not to vote in favor of a proposal to this effect at the Moncloa-Aravaca meeting; or that she maintains her refusal to recover the brightly colored mural that remembered her in Aravaca. In that neighborhood of the capital, Lucrecia Pérez was shot dead while living in poverty in a small room in what had been the Four Roses nightclub. It was 1992. Almost half a century has passed. But today’s Spain, Kenya thinks, is not yet vaccinated against racism.

–”This hurts. I’m outraged,” says Lucrecia Pérez’s daughter about the PP’s decision, agreeing with Vox.

“Criminal immigrant”. “Pateras at the bonfires”. “Stop immigration. Spaniards first.” The Madrid where Lucrecia is murdered is full of graffiti that are declarations of war. Kenya is 6 years old on the night of November 13, 1992. Her mother (“my mom,” she says) and her friend Katy cook soup by candlelight in a dilapidated, dirty, cold and soulless building, where several Dominicans survive miserably while waiting for a job that allows them to send money home and eat something hot. Civil guard Luis Merino Pérez arrives in the area with Felipe MB, alias Palalo; Víctor FR, alias Oxi; and Javier QM, the last three are 16 years old. They are neo-Nazis from Plaza de los Cubos and they are “on the hunt”.

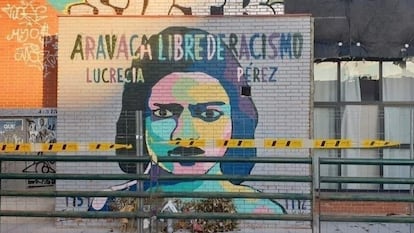

They drive a Talbot Horizon. Luis carries his service pistol with him. Victor, a mountain knife. Felipe, a knife and an awl. Almost 35 years later, a solitary graffiti remembers its victim in the heart of Aravaca. “Lucrecia lives”, we read where one day the mayor Manuela Carmena (now Madrid) allowed a mural with the face of the murdered woman to be painted, which was then covered by the current PP government with the excuse of some works to improve the insulation of the building it decorated. This Thursday there is a bouquet of flowers next to the phrase. It’s right under Lucrecia’s silk-screened face, where it slowly withers. There is no trace of the original mural. Another open wound.

“They don’t want the mural because it talks about racism,” says Amelia Romero, who at 89 (“90 in May” she specifies) is the living memory of Aravaca, of whose neighborhood association she was president at the time of the murder. “They want to erase history. But it happened.”

And so much. The main square of Aravaca was filled with protests: “You feel it, you feel it, Lucrezia is present!” On the streets of Spain, demonstrations against racism. It was a turning point. Spanish society has changed forever.

“The response was unanimous from the institutions and parties”, says Esteban Ibarra, leader of the Movement Against Intolerance, who recalls that at the time the penal code did not provide for the aggravating circumstance of racism (hate crimes), nor did there exist a specialized prosecutor’s office, nor an office for hate crimes at the Ministry of the Interior. “They didn’t give us everything, we conquered it,” he emphasizes. And he warns: “At the moment there is a regression, with a leap in quality after Covid, with enormous activity on social networks, with dynamite messages, and of great power, because teenagers socialize there.”

This impression is supported by the data. In 2024, 1,955 hate crimes and incidents were investigated in Spain: those linked to racism and xenophobia were the most numerous (41.13%; 6% less than in 2023), according to data from the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration.

Furthermore, a study on the impact of racism in Spain prepared by the Council for the Elimination of Racial or Ethnic Discrimination (CEDRE) concluded that in 2024 there was an increase in people who say they feel discriminated against because of their racial or ethnic origin in Spain compared to the previous edition of the report (2020), rising from 31% to 33%.

Finally, in the midst of the disturbances in Torre Pacheco (Murcia), due to the attack suffered by a 68-year-old man at the hands of three attackers of Maghrebi origin, 190,000 messages with characteristics of incitement to hatred circulated online in the month of July, compared to 184,000 in the previous three months, according to the Spanish Observatory of Racism and Xenophobia. A powder keg ready to explode and fueled by the far right, which has targeted unaccompanied foreign minors and illegal immigrants in general.

“There are people who in the 21st century continue to be racist, who feed on hatred, who use the networks and the media to continue to spread racism and make it grow,” complains Kenia Carvajal. After not having supported the institutional declaration nor the proposal in homage to Lucrecia promoted by Más Madrid, the PP defends its work in defense of the memory of the murdered woman. That the square that bears his name, or the monument that depicts it, were promoted under his governments. Which in previous years supported an institutional declaration of homage. If he now rejects it it is because the question, in his opinion, is repetitive, despite the fact that he considers the murder “atrocious” and condemns it without half measures. That there is no change in strategy or position.

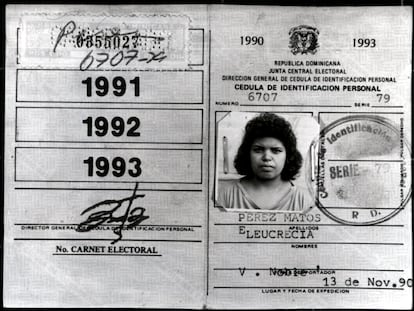

But 33 years later, his decision rekindles memories that are torture for Kenya. There is the memory of the letter from Lucrecia that her husband Alfredo receives when she has already been murdered. “When I get out of trouble, my love, I will send you $2,000 so you can leave the country and start a better business,” the handwriting of a person who no longer exists tells the widower. There is the memory of people climbing trees for mass burial on their land. And the one about the graffiti that stains Madrid while it celebrates her murder: “Lucrecia, fuck you. Skins Cubos”.

“It surprised me a lot. It really touched me,” Kenya criticizes the PP’s decision and Vox. “I don’t understand why,” he emphasizes. “My mother came to this country for a dream she couldn’t realize. They took her life because she was an immigrant. A mural and being remembered doesn’t bother anyone,” she explains. “I feel indignant. The Administration must find solutions to always help and protect the victims of discrimination, racism, and not remove a mural or a tribute, as if it didn’t matter because the murder is 33 years old”, she adds. “It matters. It hurts me and my family members. It hurts an entire country and those who live around it.”

This is the case of Romero: “What we experienced, the atmosphere that was there, was terrible. But what is happening now is more worrying because there is a generalized movement in Europe, racism is returning”. Regina Chambel, the new president of the neighborhood association, agrees. “At the time there was a lot of social tension, now it’s a very quiet neighborhood,” he says. “But the same anti-immigration hoaxes that were heard in Aravaca, which were then rumors, are now heard in the media and everywhere, in meetings, on social networks.”

Kenya’s WhatsApp is illustrated with a black and white photo of Lucrecia, who has mortgaged everything to travel to Spain. It’s the only one he has. Now he does not rule out writing a letter to Mayor Martínez-Almeida to let him know his discomfort. Because Kenya is clear about one thing: we must defend the memory of Lucrecia Pérez Matos so that the past is not repeated.