While the president of the Junta de Andalucía, Juan Manuel Moreno, defended the health management carried out by his executive at the closing of the regional congress of the PP in which he was re-elected regional president, thousands of people shouted in the streets of the whole community precisely because of “the failure of the health policy of the Andalusian government”, and asked for his resignation, a cry that until the first concentration in support of the women affected by the delay in the diagnosis of screening for cancer mama, in October 8, had not been heard in none of the demonstrations which, like the one on Sunday, had been called by Marea Blanca in the last four years to warn against the deterioration of the Andalusian public health system and its progressive privatisation.

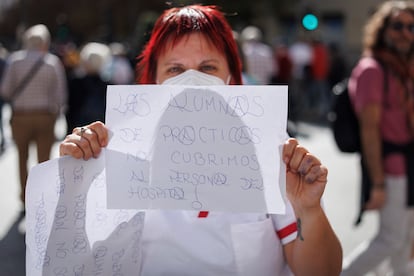

The screening scandal has given face and voice to the suffering of many other Andalusians who have had to wait more than 20 days or even three weeks for an appointment with their family doctor, like María José Romero, a pensioner from Bormujos; or a year and a half to be able to visit the traumatologist, as a nursing assistant from Seville, who prefers not to reveal her name, had to wait; or more than two years to have cysts removed from her chest, like Sandra Morán, Guillena’s administrator, who ultimately underwent surgery in a private clinic. Due to these and other problems that they or other family members suffer from, such as the lack of pediatricians or the change of family doctor, they participated in the demonstration in Seville this Sunday.

“Screenings are the tip of the iceberg, but the crisis transcends the entire public health system. The government is wrong if it believes that by fixing screenings it will silence this worsening”, warns Kati, a home care worker, who also went to Seville, together with her husband and her daughter, a social services psychologist, from Arcos de la Frontera, in Cadiz. “We attended almost all the Marea Blanca demonstrations, sometimes we went to the one in Cadiz and other times to the one in Seville,” he explains.

The first demonstration in defense of public health was held on November 26, 2022, a few months after Moreno obtained the absolute majority. During this period, despite the various health shock plans that the Andalusian government has approved (in primary care, to reduce waiting lists or to show up for family doctor visits in less than 72 hours), the feeling of deterioration of the system has been accentuated, both for users and for health workers, saturated by the lack of staff, the absence of replacements and consultations that do not decrease, as promised by the Council.

Ana Puy López, a worker at the Cenes Health Center, a few minutes from the capital Granada, knows this well and remembers that “they promised us 35 patients a day and my daily life is 50 and more”. The biggest problem, he explains, “is the lack of substitutes. This summer we had no turnover among nurses and doctors, which generates impossible pressure on those who work. Furthermore, achieving the objectives (refers to the monitoring and control of diabetic patients, polymedicated patients, those with heart failure, COPD, etc… those who periodically return to the clinic for checks) is very difficult”.

The administration sometimes offers them to work overtime in the afternoon for these patients “but then we no longer have time to live and reconcile with our family”, explains this doctor, while next to her there is a banner that says “Moreno Bonilla privatizes wonderfully”.

Added to the high stress, in the case of newly hired doctors, is the loss of enthusiasm. Eva Jiménez, Laura Allende and Elena Sánchez have been living in the capital of Granada for six months and are taking part in the demonstration. In Eva’s case, she had just left a 24-hour shift at the Ruiz de Alda hospital. The three agree: “Public health cannot do it” and insist on receiving many more patients than the established 35. “We have very high quotas”, they explain on the total number of patients under their control, “in our case, 1,300 people”. All three agree that the principle of the solution is to invest in primary care to prevent emergencies from collapsing.

The Moreno Government believes that the screening crisis is a problem limited above all to the province of Seville, since 97% of cases of dubious and unreported screening are found in the Virgen del Rocío Hospital in the Andalusian capital, and that it does not permeate the rest of Andalusian society, because it is a problem that affects women who have suffered from breast cancer. But the high turnout in capitals like Granada, with around 20,000 people marching in the streets, shows that discontent with public health transcends the screening crisis.

Something that was also seen in the Almería march: “People are fed up in Andalusia, especially in Almería. Breast cancer screenings were the last straw. It is not possible for health budgets to grow, but more and more is allocated to the private sector”, said Fernando Plaza, one of the spokespersons of the White Tide in the province of Almería, reports José Miguel Benítez.

Elena, a 36-year-old housewife, also remembered this in Seville. “This is more than simple screenings, here we are risking the future of our children, our present and what our grandparents built. They are stealing our right to public health”, she says with her son in her arms and accompanied by her daughter Estefanía, 18 years old and studying to become a Nursing Technician. “The job prospects in Andalusia are not very promising, but if we young people do not fight and take responsibility for maintaining the quality of our public healthcare system, it will have no future,” she says confidently.

The importance of Amama

Guillermo Velázquez, a family doctor from Seville and a regular visitor to all the events – this is the seventh – called by Marea Blanca, also warns about the fragility of the Andalusian public health system: “The rights gained are lost. Before we played with medical visits and now we play directly with the health of citizens”, he says on the effects of delays both in consulting with the family doctor and on delays in diagnostic tests. “We just saw it with breast screenings, but it’s happening with other types of cancer,” warns the professional.

Amama gave a face to the discomfort of going from the certainty of being healthy to the awareness that a tumor has developed within oneself, a risk of which someone has decided not to warn – according to the unofficial explanations given by the Andalusian government, “a verbal order within the health system” -.

“We are the tip of the iceberg of public health problems, but we are not the tip of any iceberg,” warns María José de la Fuente, member of Amama’s board of directors, holding on, together with the rest of the women of the association, to the banner of the Seville demonstration with the motto Our lives cannot wait.

They reject the minimization of the problem by the Andalusian PP, which limits the affected women to 2,317, of which only 2% could develop cancer and 97% of whom are concentrated in the Virgen del Rocío.

“They keep asking us: who counts? That figure was uncertain from the beginning and continues to be uncertain,” De la Fuente says. This is the case of Olga Liébana, 55 years old, from Higuera de Calatrava (Jaén), one of the many women affected by the screening who participated in the march in the capital Jaén. In 2023 she had a mammogram, but no one sent her a letter and no one called her to tell her the result. Twenty months later, a lump was noticed in her breast which turned out to be cancer. The Andalusian Health Service (SAS) cannot find the images of that mammogram nor the report or any hospitalization. “My suspicion and my concern is to think about what I would have in 2023, but they don’t give me any explanation,” says Liébana.

Although in general all the protesters insist that the public health problem goes far beyond the screening crisis, the majority believes that this scandal should represent a before and after in public health management. “The shame is that this only happens for political and electoral reasons,” complained Kati’s daughter.

Discontent is widespread, beyond projections. This is demonstrated by the massive marches in all the provincial capitals of Andalusia, despite Csif and Satse withdrawing at the last moment due to disagreements over the manifesto and the choice of route. In Seville, when an hour had passed since the women of Amama and the organizers had begun to speak to the public in front of the Palacio de San Telmo, seat of the Council, the line of the procession still ran at the height of the Murillo Gardens, about 300 meters away.