The photos of Luis’s teeth without one of the frontals and that of Daniel’s nose with the visibly deviated septum are part of the evidence collected in the report They came to hellby Human Rights Watch, made public this Wednesday. The document reveals torture and other abuses against Venezuelans in El Salvador’s Confinement Center for Terrorism (CECOT), the Nayib Bukele mega prison. There are also images of the round scars on Mateo’s hand and Carlos’ chest, hit by rubber bullets at close range while they were held in the cells of this prison.

The consequences are still visible nearly four months after 252 Venezuelan migrants endured the worst of the nightmare. US immigration police have detained them at different times, in different cities and situations – raids, at their homes, at border crossings – and on March 15 of this year, President Donald Trump decided to send them to prison in El Salvador, invoking the Alien Enemies Act and accusing them of being members of the Aragua Train gang. They experienced horror: daily portions of beatings. After an agreement between governments, mediated by the Church, on July 18 they ended up sending them to Venezuela, a country that some of them had left long ago, in some cases fleeing political persecution. In exchange for the Venezuelans, Nicolás Maduro’s government handed over 10 detained Americans to Washington.

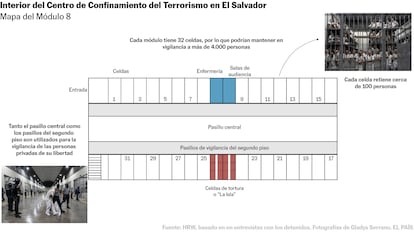

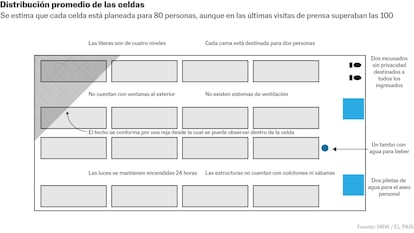

HRW, which relied on the NGO Cristosal, research centers, official documents and forensic specialists, reconstructs the Cecot torture system based on the testimonies of Venezuelans who remained for four months and three days in a place built so that almost no one could leave. The report shields the identities of the 40 victims they interviewed directly and dozens of family members, friends and lawyers they spoke with to piece together the cases of 130 of the 252 Venezuelans the Trump administration sent to Central American prison. Their names were changed for fear of retaliation and because many of them have taken legal action against the governments of the United States and El Salvador.

Daniel’s nose was broken after participating in interviews that International Red Cross personnel conducted with a group of Venezuelan prisoners on May 7. They hit him with a stick and punched him on the nose, making him bleed profusely. “They continued to hit me in the stomach, and when I tried to get air, I began to choke on blood. My nose was deflected by those blows,” the report states.

He wasn’t the only one. “After the interview, in the afternoon they came to take us out of the cell in a search position and beat us again and told us it was for informing the Red Cross about the beatings,” Flavio said. “They only beat me that same afternoon, but they beat my other classmates for the whole following week.” The psychological torture, however, was what affected him the most, the detainee said. “The most difficult thing was that the guards told us that we would never get out of there, that our families gave us up for dead.” A phrase they often repeated was that “the only way out of here (Cecot) is in a black bag”; that is, dead. The 252 Venezuelans can tell it.

The hardest beatings

On the eve of visits, such as the three carried out by the Red Cross in May and June or that of the Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem, in March, they were provided with bedding, pillows and personal hygiene products to improve their conditions. After the guests left, items were taken away from them and the beatings intensified. Two or three days before their final transfer to Venezuela, the treatment also improved, but they also gave him the final beatings.

As soon as they got off the plane they started beating them. “An officer hit me with a black truncheon in the face, exactly in the mouth, and knocked out one of my front teeth,” says Luis. Other officers also punched him in the ribs and hit him in the right knee with a baton. “The doctor who examined me later, about a week later in prison, told me that they had torn my (knee) ligament. They didn’t give me anything for my tooth,” he said, according to the report.

The investigation documented sexual violence. One inmate said four guards sexually abused him when they took him to an isolation cell called “the island,” where they regularly punished those they believed were breaking the rules with further beatings, solitary confinement and deprivation of food and water. “They played with their sticks on my body,” Mario said. “They put sticks in my legs and rubbed them against my private parts.” Then, they forced him to perform oral sex on one of the guards, groped him and called him a “faggot.” Another inmate, Nicolás, said he was sexually assaulted during the beatings. The officers grabbed his genitals and made sexual comments. “They did this to several people,” he said. “I don’t think others will tell you because it’s very intimate and embarrassing.”

HRW notes that “beatings and other abuse appear to be part of a practice designed to subjugate, humiliate and discipline detainees by imposing severe physical and psychological suffering.” Investigators warn that, according to witnesses, the security guards wore gray and black uniforms, always had their faces covered and called each other nicknames such as Satan, the Tiger, the Crow, Vegeta OR Panther and They had complete authority to treat the prisoners as they did. “The brutality and repetitive nature of the abuse also appears to indicate that the guards and riot police acted in the belief that their superiors supported or, at a minimum, tolerated their abusive acts,” the report states.

Limbo in three countries

Cecot – according to HRW – does not respect many of the parameters of international human rights law and the so-called Mandela Rules which guarantee dignified treatment of prisoners. Inaugurated by Nakib Bukele in January 2023, in full emergency regime, it has become a torture machine that is part of the institutional apparatus of the Salvadoran president. There is a history of serious human rights violations committed in this prison. “The United States sent the 252 Venezuelans to Cecot despite credible reports indicating that torture and other abuses are being committed in El Salvador’s prisons. This violates, among others, the principle of non-refoulement, established in the Convention Against Torture,” the organization denounces.

Almost everything about the process is irregular. The governments of the United States and El Salvador have refused to provide information on the whereabouts of the 252, or what their fate was, to the point that their actions – or failure to act – represent a crime of enforced disappearance under international law, the report charges. This crime occurs when a government detains a person and refuses to provide information about their whereabouts or what will become of them, leaving them without legal protection and causing further suffering for families. The detention of Venezuelan migrants in Cecot also has no legal basis, which makes it arbitrary under international humanitarian law, HRW denounces.

Once interned in Cecot, the Venezuelans were unable to communicate with either their families or their lawyers. Neither San Salvador nor Washington have ever published an official list with the names of those affected, nor have they confirmed the unofficial ones that were circulating. U.S. immigration authorities assured members of the group that they would return them to Venezuela. None of the interviewees were informed that their true destination was El Salvador.

A particular version of hell began for families, without knowing where their loved ones were and with bureaucracy transformed into an instrument of psychological torture. The names disappeared from the computer system along with the detainees’ locations shortly after the transfer and apparently “earlier than normal ICE practice.” The American lawyers of some of them denounce that the immigration authorities never informed them of their clients’ transfer.

Families found themselves trapped in a system where, when they managed to speak to someone to ask for information at ICE offices or detention centers, officials’ responses were infuriating: either their loved one’s name didn’t appear in the system, or their whereabouts were unknown, or they couldn’t provide them with information. In the best case scenario, it was confirmed to them that their relative had been deported, even if they were not told where. For some, the only solution suggested was to contact “the Venezuelan embassy in the United States,” even though it has been closed for years.

Attempts to contact the Salvadoran presidential commissioner for human rights, Andrés Guzmán Caballero, via email found only an automated message in response: his request had been transferred to the “competent institutions.” Then administrative silence.

The HWR points out that Salvadoran courts also refused to provide information on the whereabouts of the Venezuelans. Between March and July, Cristosal helped file 76 petitions habeas corpus before the Supreme Court, without receiving a response. At the end of March, the General Directorate of Penal Centers of El Salvador responded to this organization that the list of people affected by this measure had been declared confidential for seven years and for this reason they could not report their names. At the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, El Salvador assured that they had not detained Venezuelans, but rather had “facilitated the use of Salvadoran prison infrastructure for the custody of persons detained under the judicial and law enforcement system of that other State,” i.e. the United States.

With their release, only part of the nightmare for these men has passed. “I’m always on alert because every time I heard the sound of keys and handcuffs, it meant they were already coming to beat us,” Daniel told HRW. The detainees assured that they were psychologically affected by what they experienced. In Venezuela, they carried out medical checks, official media interviews and background checks before bringing them home. They did not receive psychological support to deal with the resulting trauma. The report indicates that two detainees said that agents of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN) visited their homes after their return. “I live in fear,” many of those interviewed said. According to the report, officers said the visits were “part of a monitoring process.” They asked them to record videos about their detention in the United States, the treatment they received and asked, among other things, whether they had ties to US agencies seeking to “destabilize the government.”